Posted on:

Modified on:

- Introduction

- Matthew’s Version, 5:3–7:29

- The Beatitudes, Mt 5:3-12

- Salt and Light, Mt 5:13-16

- Endorsement of Torah and the Mosaic Covenant, Mt 5:17-19

- Righteousness, Mt 5:20

- The Six Antithises, Mt 5:21-48

- Ostentatious Giving, Mt 6:1-4

- Ostentatious Prayer, Mt 6:5-8

- The Lord’s Prayer, Mt 6:9–15

- Forgiveness, Mt 6:14–15

- Ostentatious Fasting, Mt 6:16-18

- Greed, Mt 6:19-24

- Anxiety, Mt 6:25-34

- Judgementalism, Mt 7:1-5

- Dogs and Pigs, Mt 7:6

- Prayer and Relationships, Mt 7:7-11

- The Golden Rule Mt 7:12

- The Narrow Gate, Mt 7:13-14

- False Prophets, Mt 7:15-23

- Wisdom, Mt 7:24-27

- Luke’s Version, 6:20–49

Introduction

Pretty much everyone who has been attending church for any length of time is at least somewhat familiar with Jesus’ “Sermon on the Mount“, recorded by Matthew in 5:3–7:29, and with His so-called “Sermon on the Plain”, recorded by Luke, mostly in verses 6:20–49. I’ll explain below why I think these are the same event. Much of the two passages is fairly well understood, but at the same time, I think there is a lot of misunderstanding, as well. In this post I want to go through both passages and discuss some things that I think need clarification for modern readers. My concentration will be mostly on the Matthew account, since it is more complete and better organized.

Since this is intended to be a survey, I will try to resist my normal tendency to comment on each verse. Instead, I’ll concentrate on pointing out where I think there may be common misunderstanding.

What and where

The events discussed here occurred very early in Jesus’ public ministry, possibly as early as three or four months after His baptism.

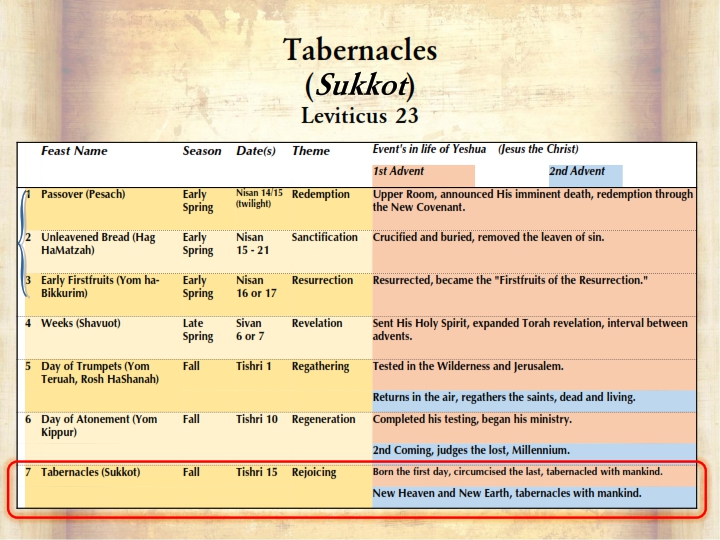

Jesus began His ministry, not at His baptism as is commonly taught, but at Yom Kippur at the conclusion of His Wilderness testing. This event is mostly ignored in Christian churches.

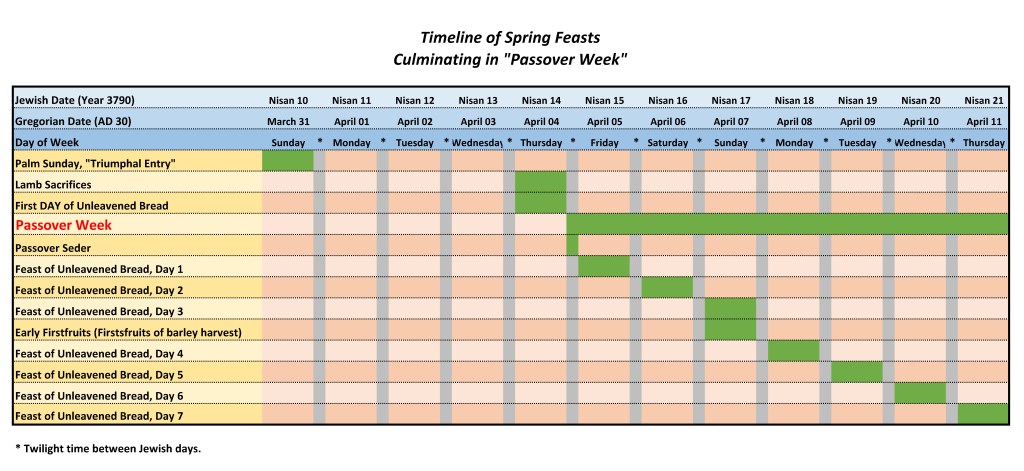

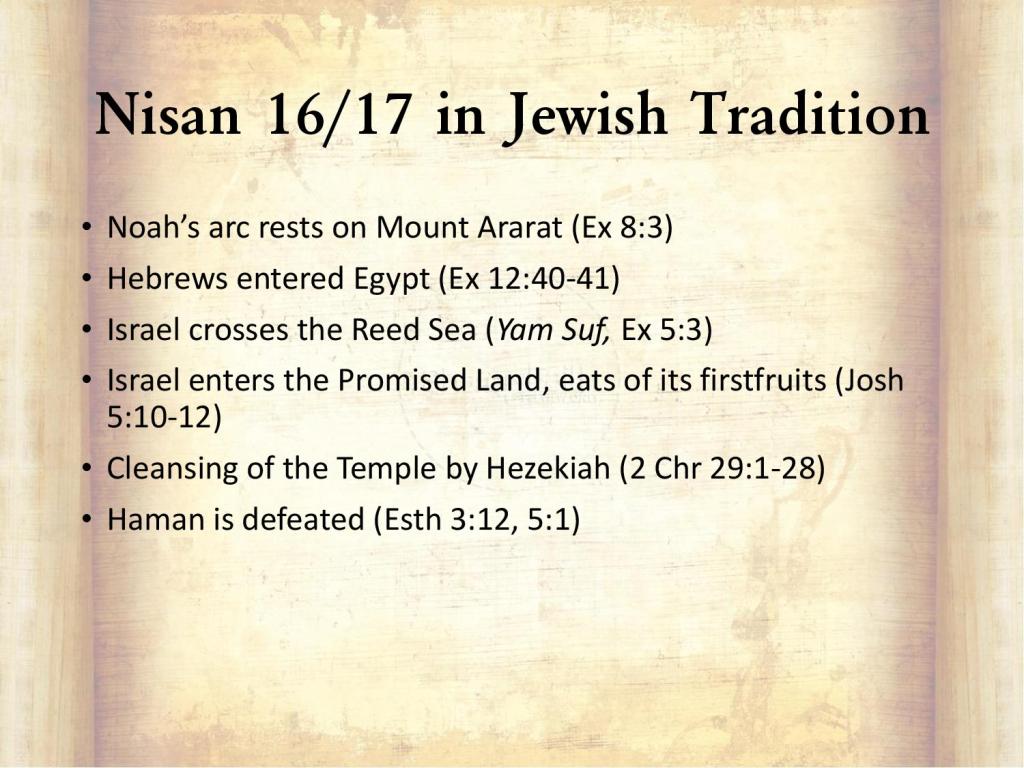

In 2020 rewrites of my early articles on The Jewish Feasts, I was able to date all of the crucial events of Jesus’ first advent. His baptism occurred in the early fall, on the Hebrew Date Elul 1, in the Julian/Gregorian year AD 26. Elul 1 was the day each year when Jews around the world would gather around streams and mikvoth (baptistries) for ritual immersion and cleansing from sin. This prepared them for 40 days of prayer, fasting, introspection, repentance, and restitution where appropriate. It was necessary for the Messiah to demonstrate His Jewishness by participating in this important annual act of faith.

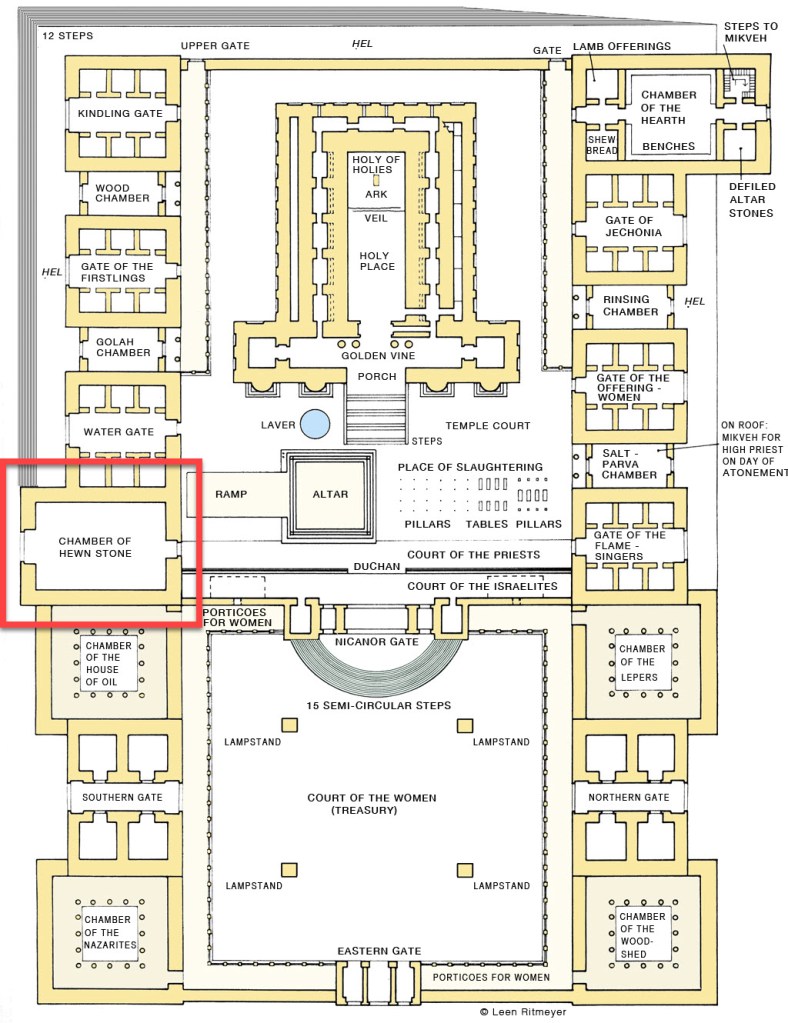

Jesus, of course, spent His own 40 days in the Wilderness. This culminated, I believe, with His testing by Satan on the final day, Tishri 10, which is Yom Kippur. Please read my short post, The Two Adams, where I discuss the background, timing, and crucial theological importance of this testing. Recall that one of the three temptations, probably the final one, took Jesus to the Pinnacle of the Temple, probably the Place of Trumpeting, near the western corner of the southern retaining wall, where thousands of holiday pilgrims would see His failure if He took Satan’s dare and jumped.

Jesus then began His ministry in Jerusalem during Sukkoth, the joyous week of the Feast of Tabernacles. During this time, He began healing and teaching, and He picked up the first few of His twelve closest disciples.

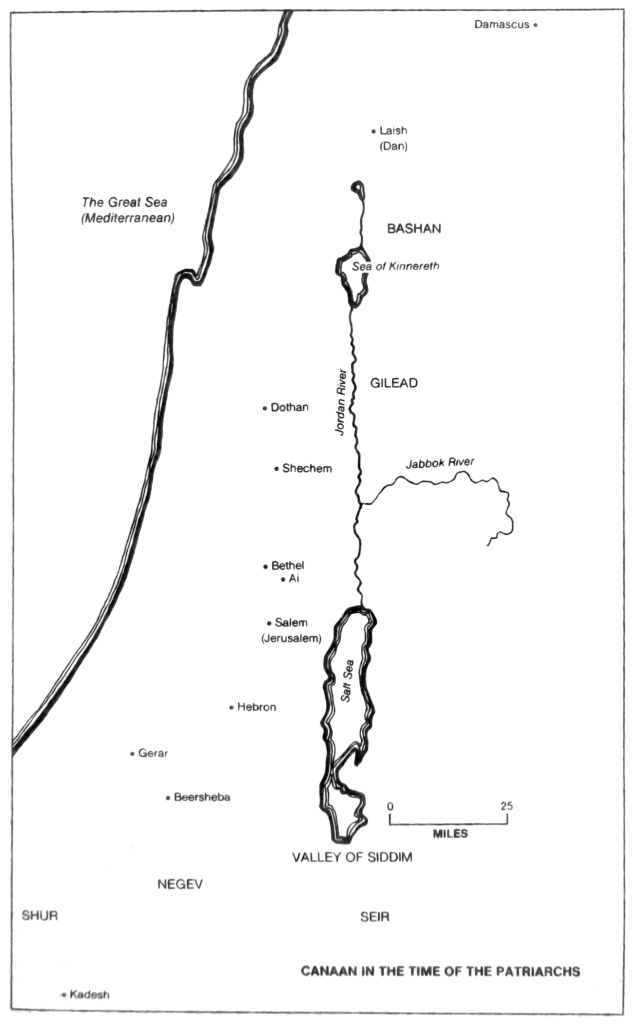

After a short period in Jerusalem, Jesus returned to Nazareth, then lived for a while in Capernaum, on the north shore of Lake Kinneret (the Sea of Galilee). Evidently, the “Sermon on the Mount” was delivered shortly thereafter, and in that region. Given its purpose (see below), I think that an early winter date is likely. The Galilee daily temperature range for December is currently around 50–60 °F (10–16 °C)

Luke records a similar “sermon”, but due to differences in the text and to Luke’s apparent description of it as occurring on a “flat place”, most people seem to assume that these were separate events. In my opinion, it’s just one event. In support of that view:

- Differences in text between gospels is not at all unusual. 1st century literary standards did not require exact quotation—paraphrasing was fine, as long as it did not materially change the argument(s) being made. With the same proviso, even loose chronological ordering was permissible.

- Matthew was present at the event, and much later (probably 10 to 25 years later) he wrote down his impressions of what he, himself, witnessed. Inerrancy requires only that the substance of his report is correct, not that every word is faithfully repeated, and in the correct order, unless, as stated above, it alters the message intended. Luke, on the other hand, was not present and recorded only what he got, second-hand, from other sources. Of course, he must be held to the same standards of inerrancy, so his report may be assumed to be less accurate in the telling, but just as accurate in substance.

- Matthew was born a Jew, and though he was first mentioned as a hated tax collector, he was steeped in Jewish tradition and Messianic hopes. His other recorded name, Levi (pronounced Lev-EE), indicates that he was from the tribe of Levi, and therefore even more immersed in Torah training in his home. Jesus’ teaching and miracles were central to Matthew’s gospel. Luke is the only Biblical author thought to be from a gentile heritage, but he is also thought to have legally converted to Judaism. His knowledge of Scripture and Jewish tradition would of course have been less complete than Matthew’s, and his gospel reflects more of Jesus’ humanity and details of His ministerial travels. It’s not surprising that he was silent about some of the more Jewish themes that were important to Matthew.

- The passage in Luke is called the “Sermon on the Plain” because it mentions a “flat place”. I believe that this discrepancy can be resolved by harmonizing the two passages, thus:

- Jesus traveled to Capernaum. Mt 4:12–16; Lk 4:31.

- He then began teaching in or around Capernaum. Mt 4:17; Lk 4:32–44.

Note: The ESV translates Lk 4:44 as, “And he was preaching in the synagogues of Judea.” Other translations say, “He kept on preaching…”, or something similar. The problem I see here is that the previous and following verses all clearly have Jesus in the Capernaum area. But the Greek Ἰουδαίας (Ioudaios) is a tricky word to translate. Very similar forms of the word can mean, “Jews”, “Judeans”, “Judea”, “tribe of Judah”, “land of the Jews”, and so on. Thayer’s Greek Lexicon, which provides a lot of supporting evidence, translates this particular form as “Jewish“, or more precisely, when joined with a noun as “belonging to the Jewish race.” I would comfortably contend, then, that Jesus is not here reported as going back to Judea at this time, but rather, “he was preaching in the synagogues of the Jews.” - He collected a following, the disciples and other groups, some locals, some following from other regions, and of course the ever-present “scribes and Pharisees”, who I believe to have been agents from the Sanhedrin. Mt 4:18–23; Lk 4:45–6:11.

- One evening, He “went out to the mountain”, presumably a hill near Capernaum, and spent the night in prayer. In the morning, He called for His new disciples to join Him. Lk 6:12–16.

- After they joined for the traditional Shacharit (morning) prayers, the group then went down off the mountain to a “level place”, perhaps a valley floor or the lake shore, and ministered to a very large group of people from all over Galilee and the surrounding regions: from the Mediterranean coast to the west, Jerusalem to the south, and Decapolis and Transjordan to the east. Mt 4:24–25; Lk 6:17–19.

- Tiring of dealing with the crowd, Jesus walked back up the hill, with His disciples following Him. He sat down, and the others drew in to listen. He then began teaching, what we now call the “Sermon”. Mt 5:1–2.

The audience

I conclude from the above that Matthew and Luke describe the same event. Aside from that, it also tells me that the event was not a sermon at all, but rather an intimate teaching event, with Jesus sitting on the ground, and his disciples sitting in front of him.

Jesus had begun gathering a group of talmidim (disciples), beginning with a few in Jerusalem after His testing, and adding more in Galilee. It is impossible to say how many there were, and how many stuck with Him, but in Luke 6:13, he selected 12 of them to be ἀποστόλους (apostolous, emissaries, ambassadors). Some of those culled may have continued following Him but were not included in His inner circle.

Though the apostles were with Him during His first forays among the people, I think that the “Sermon” was probably the first formal teaching session they received from Him.

Who was included in the audience? Certainly the 12. Possibly additional, non-apostolic, disciples. Meanwhile, other people may have tagged along from the crowds on the flat area and still more may have come later. By the time He was done speaking, a crown had gathered, Mt 7:28.

Matthew’s Version, 5:3–7:29

What Jesus taught those assembled on the mount was specifically Jewish, and beyond that, specifically for the disciples. If the final audience (including late arrivals) included gentiles, say from Tyre, Sidon or Decapolis, the message was not intended for them.

The Beatitudes, Mt 5:3-12

Whether you’re reading Matthew’s list or Luke’s, the way almost everyone reads the Beatitudes is as cause followed by effect: Because you are poor in spirit—by one interpretation, spiritually depressed, or by another, spiritually bankrupt—the Kingdom of Heaven is yours! The blessing is because of, or in compensation for, the suffering.

Not so! That may fit with the popular (but wrong) idea that people have to be convinced of their sin before they can be saved. Why wrong? Because salvation, throughout all of human history, has been by grace alone through faith alone. By “calling on the name of the Lord”, which is another way of saying, by trusting faith, as illustrated in Hebrews 11 and elsewhere. One may be driven to faith through “conviction of sin”, or through witnessing God’s healing, or something else that has grabbed his or her attention. My own faith dates from my childhood, before I understood the sin concept. I became acquainted with Jesus through the children’s Bible stories, and I’ve never doubted Him since I was around 8 years old.

No, it is the other way around. Those who have been and perhaps still are the poor in spirit are blessed because the Kingdom of Heaven is theirs. Once they arrive, their spirits will certainly no longer be poor. The plain old poor are blessed because the Kingdom of God is theirs, and they will no longer by needy in any way. In fact, this is expressed plainly in Luke 12:22–32.

Because He is talking specifically to His disciples, particularly the 12 who will take the Gospel to the world, I have to believe that each of the Beatitudes expresses either, “this is how you are” or “this is how I expect my apostles to be.”

I have read that each of the Beatitudes is a New Testament expression of an Old Testament promise. For this survey, I’ll not take the time to research that, but I do want to comment on Mt 5:5:

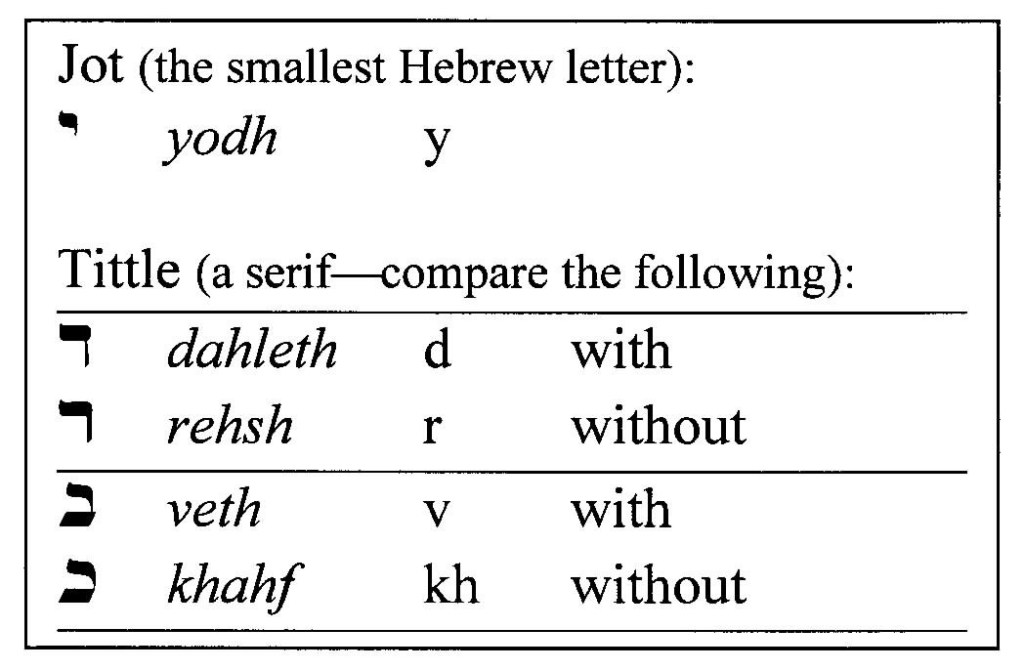

Most translations say that “the meek … will inherit the earth.” This is absolutely a bad translation! The Greek γῆν (gēn) is usually translated as “earth”, meaning specifically the solid part of the entire planet. But it can also be translated as “land”, meaning a region or country. In this case, “land” is the only possible translation, because the verse is a quotation of

Psalms 37:11 (CJB)

[11] But the meek will inherit the land

and delight themselves in abundant peace.

David’s theme in Psalm 37 is, “Don’t be upset by evildoers or envious of those who do wrong”, because they will wither like grass, while those (Jews) who do good will “settle in the [Promised] land, and feed on faithfulness.” Israel’s meek and oppressed Jews will one day experience God’s shalom (peace, wellness, prosperity, etc.) in the Land He has given them to possess.

In Mt 5:9, “those who make peace … will be called sons of God”: “Sons of God“, huios Theos in Greek and bene haElohim in Hebrew, technically refers to the Heavenly Host (angels) who have not rebelled, but it will also refer to those humans who ultimately abide in Heaven with God. Another word for Sons of God is “saints.” Yes, the good angels are saints, too.

Salt and Light, Mt 5:13-16

This and the following section do not appear in Luke’s account because they are of exclusively Jewish application. Even though Luke was a Jewish proselyte, his background was gentile and secular. His two books, Luke and Acts, were written to a man who went by the Greek name, Theophilus, who is thought to have been either a gentile foreigner, maybe in Alexandria, or possibly the Sadducee, High Priest Theophilus ben Ananus, who served from AD 37 to 41. Whoever he was, Pharisaic Jewish detail was probably not among his interests.

In this section of His message, Jesus is commissioning His disciples to first, be a preservative influence on the believing Jews of Israel (salt), and second, lead those Jews into the surrounding world as evangelists to the lost (light). Two completely separate functions. Proper application to the church is (a) discipleship, teaching, fellowship, etc. within the Church (salt), and (b) evangelism of the lost (light). I cringe when I hear Christians say, “We are called to be salt and light to the world.” That’s just not the right concept!

Since I have previously written on this subject in depth, I would ask you to review it in “Light Yes, But Why Salt?“.

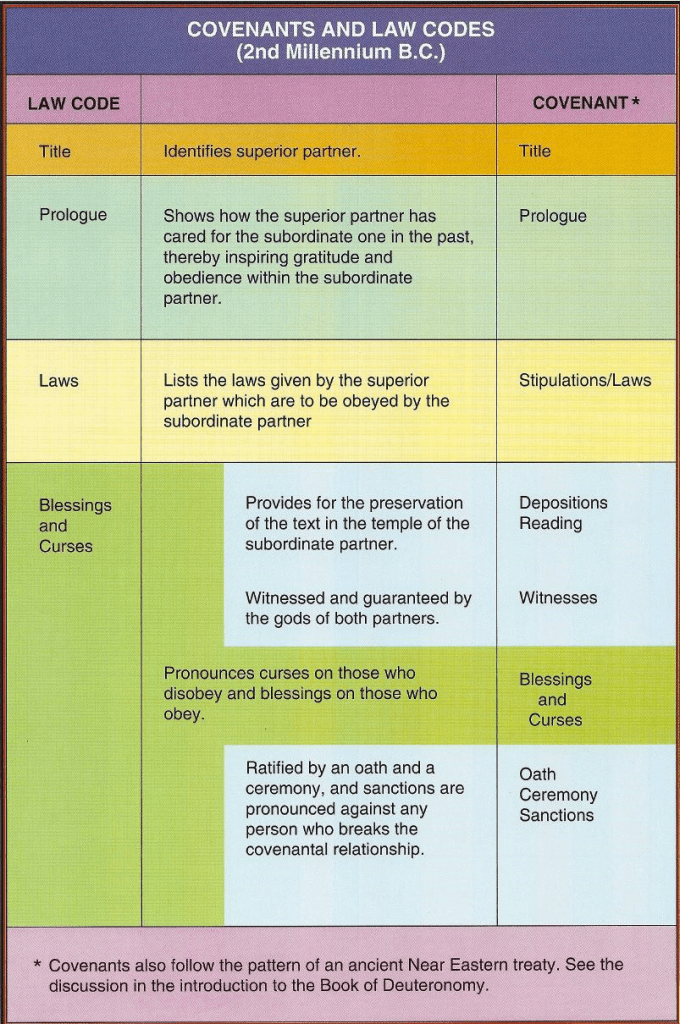

Endorsement of Torah and the Mosaic Covenant, Mt 5:17-19

He then reminds them that nothing He will teach or that they are to teach must ever detract from Jewish reverence to “the Law”, which will endure until the end of time. Again, this is Jewish teaching, for Jews!

I have also, more recently, written an in-depth discussion of this subject in, “Fulfilling the Law: Matthew 5:17–19“.

Righteousness, Mt 5:20

English translations like ESV that insert section headings tend to lump Matthew 5:20 with the previous verses, 17–19. This very much serves to reinforce the badly mistaken view, held by a majority of Christians, that because Jesus fulfilled the Law (and the prophets?), they are no longer valid. No, no, a thousand times no!!!

In reality, verse 20 is prologue for what follows! The next 28 verses (see my next section), in particular, discuss legalistic interpretations of Torah, not as taught, but as practiced by many (not all) of the Pharisees.

There is an interesting play on words in this verse—a “Hebraism”. In Hebrew, which was probably the language Jesus was speaking to His disciples, the word for “righteousness” is צֶדֶק (tsedeq; The Greek equivalent is δικαιοσύνη, dikaiosune).

Every Scribe (the academics) and Pharisee (the sectarians) strove to achieve a reputation for tsedeq by living his life as a just, honest, and compassionate man, ethically superior in all respects. Of course, the “easy” way to achieve this was by obedience to the 613 mitzvoth—by checking boxes. One of the most visible acts of righteousness was almsgiving. To say that one was a tsedeq was essentially to say that he was a generous almsgiver.

But Jesus was implying here that almsgiving isn’t enough to be considered truly righteous. True righteousness demands true faith.

Matthew 5:20 (ESV) additions mine

[20] For I tell you, unless your righteousness [your faith] exceeds that of the scribes and Pharisees [their almsgiving], you will never enter the kingdom of heaven.

Every Jew present would immediately have also understood the term tsedeq as an expression of one of God’s primary attributes—none is more important than His righteousness. In fact, one of His many names is Yhvh Tsidqenu: The LORD Our Righteousness.

In His personal life to that point and in His ministry to follow, Jesus faithfully kept the commandments of Torah, but His teachings were primarily about faith and the Kingdom of Heaven. Paul also emphasized the righteousness of faith.

The Six Antithises, Mt 5:21-48

I have heard and read many claims that Jesus was here contradicting the Torah commandments, or else deprecating or radically amending them. I believe that Jesus’ endorsement of Torah, above, was deliberate prologue to this section. There should be no doubt that He was engaging in commentary (Hebrew midrash), not revision!

Some of these are from the “Decalogue“, or 10 Commandments, and some were from other portions of the Levitical commandments dealing with relationships between Jews. The subjects in order, are:

- Murder, vs 21–26.

- Adultery, vs 27–30.

- Divorce, vs 31–32.

- Breaking an oath, vs 33–37.

- Vengeance, vs 38–42.

- Hatred, vs 43–48.

In each case, Jesus did not advocate disobedience to the commandments, but rather He told His followers to take them in the spirit God intended and to apply that same spirit to analogous situations that were more common to most people.

In fact, much of this was not even originally Jesus’ words. In those days, the two most powerful rabbinic schools of interpretation were the House of Hillel and the House of Shammai. Shammai’s interpretations were always harsh and legalistic, while Hillel’s were more nuanced and humanitarian.

Jesus was essentially, as always, taking Hillel’s side in an ongoing argument. It may sound like Jesus was advocating tougher rules. But think about them from a victimhood perspective: The brother who is hated or berated; the sexually harassed woman; the unjustly divorced wife; the person victimized by a broken oath, and so on.

Ostentatious Giving, Mt 6:1-4

Right after His snide comment about the “righteousness of the Pharisees”, Jesus first (by Matthew’s account) listed a number of commandments (the “antitheses”) for which box-checking obedience falls short of spiritual understanding, and then He turned to several very specific examples of ways in which many Pharisees demonstrated a deficiency in their own righteousness.

Verse 1 of this chapter is an introduction to several passages dealing with the hypocrisy of “practicing your righteousness before other people in order to be seen by them”.

First on this list was the propensity of many to turn their almsgiving into bragging rights (as discussed above). Almsgiving for public recognition qualifies as hypocrisy.

Ostentatious Prayer, Mt 6:5-8

Next, Jesus addresses the similar issue of those who pray flowery public prayers in order to impress other humans.

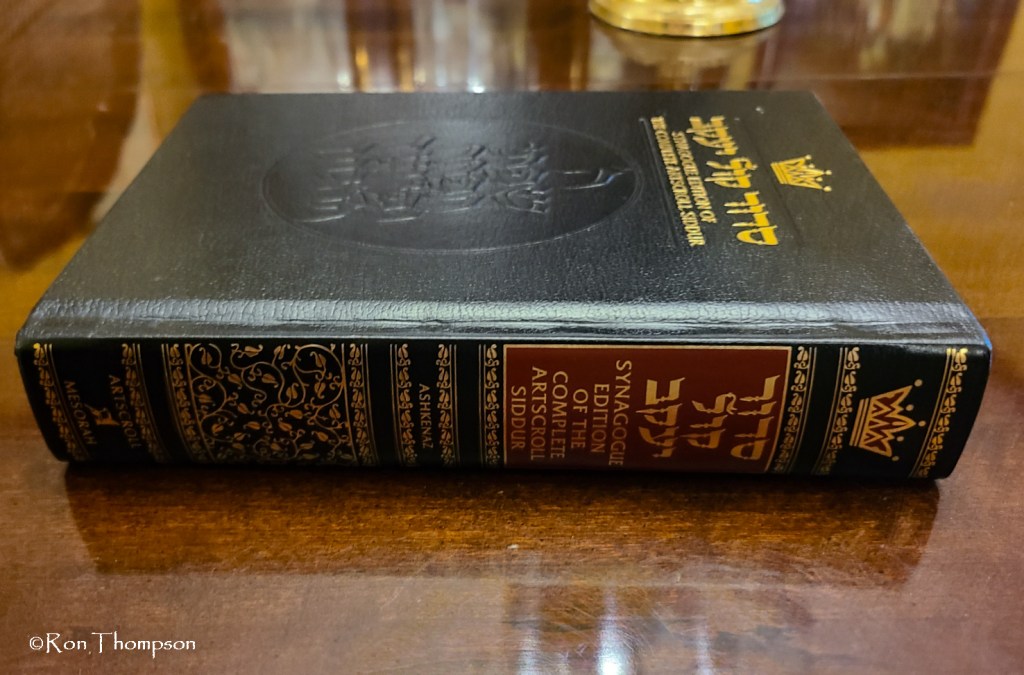

The Bible has a lot to say about prayer—but little about spontaneous prayer, which appears to be what this passage has in view. There is nothing I’m aware of that actually indicates that spontaneous prayer should be verbal. From at least the Babylonian captivity, and most likely as far back as the early Monarchy, until today, most verbalized Jewish prayer has been memorized or later, read from a Siddur (prayer book). For most of the last two millennia, where Jews have prayed spontaneously in group sessions, it has been by “davening” (quietly moving the lips), not by speaking out loud. For way more on this subject, see The Roots of Christian Prayer.

On a personal note: I am a decent writer, but a horrible public speaker. I'm aware that the secret to public prayer is to forget there are humans listening and to direct my words to God. Unfortunately, at 77 years old and having been in church since I was a toddler, awareness and performance have never come together. Every time I have been roped into "leading prayer", I've found myself addressing those around me, not Him within me. So, to avoid feeling like the Pharisee on the street corner, I refuse to be roped in again!

The Lord’s Prayer, Mt 6:9–15

Having condemned self-aggrandizing public prayer, Jesus then digresses to teach his disciples a prayer that I believe was meant to be an anthem to set them apart from other rabbinical schools, not a model form of prayer as most people today assume.

Whether it was meant to be recited in unison, davened, or sung, I can’t say for sure. I’m doubtful that there was unison recitation at all in the synagogues or Temple. Davening was certainly possible, with the leader reciting aloud and the others moving their lips. But Biblical Judaism was full of songs. The Psalms were probably all intended for song. We can only speculate on how singing was done. Most scholars seem to think it was antiphonal, either chant or melody.

The following is how I envision it:

Matthew 6:9b–13 (CJB) with voices added

— Cantor:

[9b] Our Father in heaven!

May your Name be kept holy.

— Congregation:

[10] May your Kingdom come,

your will be done on earth as in heaven.

— Cantor:

[11] Give us the food we need today.

— Congregation:

[12] Forgive us what we have done wrong,

as we too have forgiven those who have wronged us.

— Cantor:

[13] And do not lead us into hard testing,

but keep us safe from the Evil One.

— Congregation:

For kingship, power and glory are yours forever.

Amen.

Forgiveness, Mt 6:14–15

The ESV and CJB, among others, have translated the compound particle that begins verse 14 as if these two verses were a commentary on verse 12, and since ESV has grouped them under the same heading as the prayer, that is obviously the way they view it.

It may be that, or it may be a completely separate brief statement about forgiveness, in which case the particle should probably have been rendered as something like “provided that” or “if” (you forgive).

What is to be forgiven in verse 12 is ὀφείλημα (opheiléma), any kind of debt or obligation, either monetary or otherwise, where something is owed. Verse 14 uses a noun with a narrower scope: παράπτωμα (paraptóma), meaning a fault or offense that has been committed. Though some form of restitution or penalty may be owed, it seems to me a stretch to connect the two terms like this.

Ostentatious Fasting, Mt 6:16-18

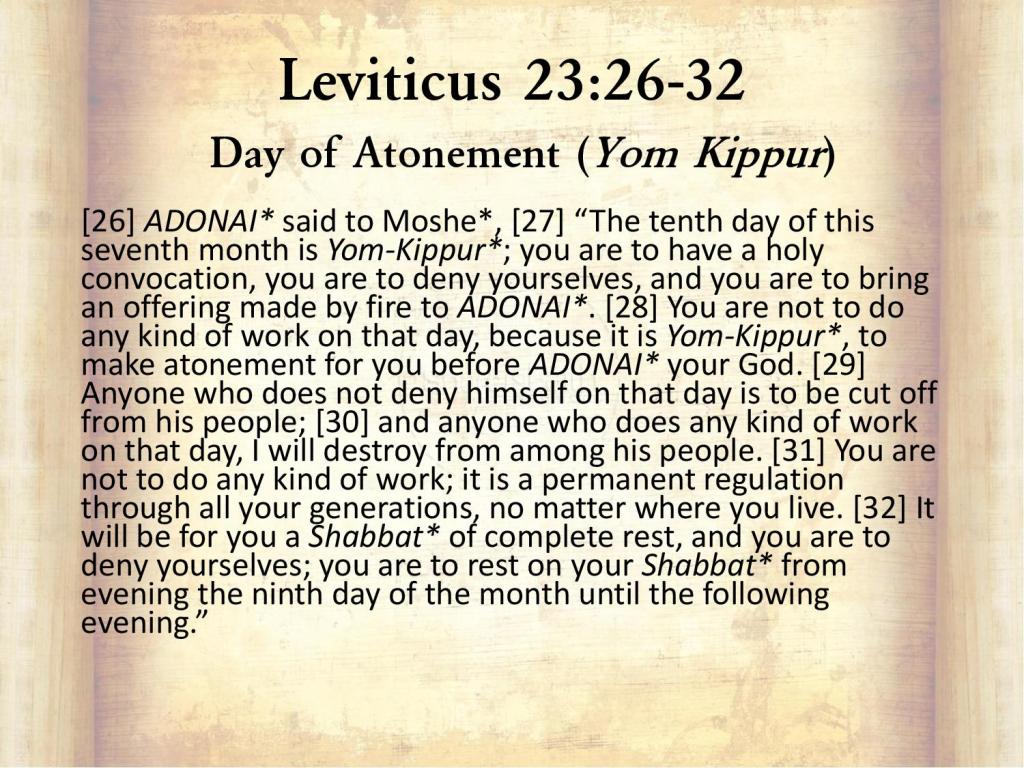

Once again, Jesus calls out hypocritical worship. Fasting was a frequent requirement under Oral Torah, i.e., the “traditions of the Jews”, though Scripture only specifies one day a year for fasting (Yom Kippur, on 10 Tishri), and it says nothing about how long one should fast on that day or what, if anything can still be consumed.

Greed, Mt 6:19-24

This section contains the infamous “single eye” reference (verses 21 and 22) that almost nobody in all of Christianity understands. Even the “Cultural and Historical Background” given by Strong’s is inapplicable. That’s because this is a Jewish idiomatic usage of the Greek word.

The simplest way to explain it is to quote it from the one translation I’m aware of that gets it right:

Matthew 6:22 (CJB) the bracketed text is the translator’s

[22] ‘The eye is the lamp of the body.’ So if you have a ‘good eye’ [that is, if you are generous] your whole body will be full of light; [23] but if you have an ‘evil eye’ [if you are stingy] your whole body will be full of darkness. If, then, the light in you is darkness, how great is that darkness!

Anxiety, Mt 6:25-34

This passage on faith in the face of anxiety is about as clear as it gets.

Judgementalism, Mt 7:1-5

Again, I don’t think there is very much to this passage that needs explanation, except to say that it does not, as many think, say that it is never proper to judge the actions of others. Verse 5 makes it clear that judgement is acceptable, provided that one first deals with his or her own sin.

Dogs and Pigs, Mt 7:6

Matthew presents this verse without explanation. It is most likely a proverb that was known and understood by the Jews in attendance. If “dogs” and “pigs” are humans, then Jesus is warning His followers not to entrust that which is holy to people who are unholy. In that case, it is probably connected to the previous passage, since to recognize one requires judgement.

Was Jesus, then, engaging in racism? Please, that concept is anachronistic.

Christianity didn’t yet exist. Biblically, there were two classes of people: Jews and goyim (gentiles). Ideally, Jews worshipped Yahweh. Gentiles mostly worshipped pagan gods. Gentiles living in Israel (the ger, or “stranger”, “sojourner”) could convert to Judaism and worship Yahweh, and Jews were to treat those proselytes as other Jews. Gentiles living in Israel who did not convert were required to live righteously and were to be treated well by Jews if they did so.

Though most Godly Jews did distrust, dislike, or even hate gentiles because of their paganism, calling them dogs or pigs didn’t necessarily carry the same animas as racial epithets today. Uncircumcised gentiles were considered ritually unclean, just like dogs and pigs. It was a description, not an epithet.

Since pigs were commonly used for food in gentile lands, comparing a gentile to a pig was probably an especially poignant image to a Jew.

Dogs were also ritually unclean, but since they weren’t commonly eaten by the gentiles, they weren’t as reviled as pigs. In fact, they were sometimes Jewish pets, especially as puppies.

Saying, “Do not give dogs what is holy” was probably an expression based on:

Exodus 22:31 (ESV) emphasis mine

[31] “You shall be consecrated to me. Therefore you shall not eat any flesh that is torn by beasts in the field; you shall throw it to the dogs.

A number of commentaries speculate that Jesus is saying, “You can throw carrion to the dogs, but not meat sacrificed to God.” My guess is that He was saying that any clean (and therefore holy) object, not just sacrificial meat, should not be offered to unholy gentiles.

Other possible interpretations could be gleaned from the observation that the same Greek word translated as “dogs” was sometimes rendered as “prostitutes”:

Philippians 3:2 (ESV) emphasis mine

[2] Look out for the dogs, look out for the evildoers, look out for those who mutilate the flesh.

Prayer and Relationships, Mt 7:7-11

This passage is, of course, about prayer. From the context, “ask”, “seek”, and “knock” are all talking about prayer. With that in mind, interpretation is fairly easy.

However, caution is in order. Prosperity gospel will say that this is a firm promise, and if you don’t get what nyou ask for it’s because you are somehow at fault. Perhaps there is sin in your life, or maybe you asked in an improper spirit.

I may be accused of heresy for this, but passages like this aren’t promises, they are rules of thumb, so to speak. God is not obligated to give even the Godliest person everything requested every time. God has His own agenda, which is not necessarily for us to know.

There are many examples of these “general principles”. To name just two: “Train up a child in the way he should go; and when he is old, he will not depart from it.” “The days of our years are threescore years and ten.”

The Golden Rule Mt 7:12

I mentioned above that parts of the Sermon on the Mount were Jesus’ restatements of principles already recognized in Judaism. That should not be a surprise. He did not come to overthrow Torah, in any sense. God is the author of Torah, and Israel was His elect people, tasked with transmitting, interpreting and managing Torah. These supervisory functions were, in fact, what Jesus was referring to at Caesaria Phillippi when He later granted the same rights to His apostles:

Matthew 16:19 (ESV)

[19] I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven, and whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven.”

What I believe was Jesus’ goal in this first lecture to His new band of apostles was to sort out the good from the bad that had developed in the ranks of the theologians of Israel.

The Golden Rule actually wasn’t even a “Jewish invention.” Every ancient civilization had a similar saying, going back at least as far as early Egypt. In Judaism it appeared as early as the Apocryphal book of Tobit, written in the 3rd century BC:

Tobit 4:15 (NRSV) emphasis mine

[15] And what you hate, do not do to anyone. Do not drink wine to excess or let drunkenness go with you on your way.

In the 1st century it was, once again, couched in terms of the disputes between the humanist, Hillel and the legalist, Shammai:

From Shabbat 31A (emphasis mine):

A. There was another case of a gentile who came before Shammai. He said to him, “Convert me on the stipulation that you teach me the entire Torah while I am standing on one foot.” He drove him off with the building cubit [a measuring rod] that he had in his hand.

B. He came before Hillel: “Convert me.”

C. He said to him, “‘What is hateful to you, to your fellow don’t do.’ That’s the entirety of the Torah; everything else is elaboration. So go, study.”

— Neusner, Jacob, ed., The Babylonian Talmud: A Translation and Commentary. Accordance Electronic edition, version 1.6. Peabody: Hendrickson Publishers, 2005.

The Narrow Gate, Mt 7:13-14

This passage is self-explanatory.

Bonus material: Speaking of narrow gates, you’ve probably heard the following explained by reference to an obscure Temple gate called the “Needle’s Eye”:

Matthew 19:24 (ESV), also Mark 10:25; Luke 18:25

[24] Again I tell you, it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich person to enter the kingdom of God.”

There is no such gate! But nothing is impossible for God.

False Prophets, Mt 7:15-23

The two passages that ESV titles “A Tree and Its Fruit” (15–20) and “I Never Knew You” (21–23) form a single united theme, in my opinion. That theme is about recognition of false prophets.

I don’t believe that true prophets, in the Biblical sense, still exist today, but application can be found in the evaluation of anyone who claims to have special knowledge imparted by God that is not available to anyone else.

While judgementalism is condemned in some portions of the Bible, that can’t be considered a blanket prohibition. If we are to recognize false teaching and avoid victimization, certainly we must be free to evaluate others on the basis of results, as Jesus warns in verse 15.

Wisdom, Mt 7:24-27

I assume that children today are taught the lesson of the wise man and the foolish man, as I was way back in the day.

Luke’s Version, 6:20–49

While Matthew’s version is “very Jewish“, with frequent references to Old Testament theology, Luke’s version includes little, if anything, that is applicable specifically to the Jewish culture, though he is describing the same event.

Also, Luke apparently was not scrupulous about keeping all of his comments about the Sermon grouped in one place.

I’m not going to attempt even a complete survey of Luke’s Sermon on the Plain. Just random comments.

Blessings and curses, Lk 6:20–26

Where Matthew gives a list of blessings (the Beatitudes), Luke lists both blessings and curses.

The blessings are basically a subset of the promises in Matthew’s list.

In verse 20, Luke’s version would seem to be saying that because you are poor (lacking money), the Kingdom of God is yours. I can’t see any interpretation that would rescue that logic! Nor will you be blessed with financial riches once you arrive in the Kingdom of God. There is no “mansion over the hilltop”. If the streets are gold, it won’t belong to you. What you will possess is relief from suffering you may undergo now because you lack resources on earth.

After his abbreviated list of blessings, Luke listed four woes, traits that He won’t tolerate in His disciples: “I don’t want you to be rich, sated, frivolous, or fawning”. Temporal worldly gain may cost you in eternity.

Miscellaneous discourses, Lk 6:27–49

The rest of the chapter could be a continuation of the “Sermon” but could just as well be later lessons. Most of it consists of discourses on confrontational ethics.

This section begins with a discussion of loving one’s enemies 6:27–36, which is analogous to Matthew’s 6th Antithesis. Of the six, this is the only one that is strictly related to an attitude, as opposed to a Torah commandment, though it is mentioned in Leviticus in relation to vengeance. If this is still part of the Sermon, omitting the first five is consistent with Luke speaking to a gentile audience.

Being accepted as a disciple under a respected Rabbi entailed exceptional responsibility and required total obedience to the Master. Without question these were rules that Jesus expected His disciples to obey scrupulously, as they already presumably did with respect to the 613 Torah commandments.

Yet the passage, especially as expressed in Luke 6:27–30, contains exhortations that most of us have a difficult time obeying: “Love your enemies”, “bless those who curse you”, “turn the other cheek”, “let people rip you off”, and “give more than requested”. I don’t want to encourage bad behavior, but I have to put this in perspective, as I see it.

As gentile believers in the New Testament Church, good behavior is expected of us, too, but given our frailty in the face of challenging circumstances, I don’t recommend excessive judgementalism…

And, low and behold, the next topic on Luke’s agenda here is judgementalism, verses 37–42.

In verses 43–45, we see, as in Matthew, that judgement precedes “fruit inspection”, or recognizing false prophets by their fruit.

I suspect that the end of the chapter, verses 46–49 may be for a subsequent discussion with the disciples, because verse 46 implies a longer history together than is likely from this early teaching session, virtually right after Jesus commissioned His apostles.

The Lord’s Prayer, Lk 11:1–4

Luke’s report on the prayer is in chapter 11, and clearly out of chronological order.

Verse 1 adds credence to my contention (not my own idea but garnered from the book Jesus and the Victory of God, by N.T. Wright) that it was a rabbinic anthem, since John the Baptizer had previously taught a similar prayer to his own disciples.

In any case, the suggestion that Jesus’ disciples didn’t know how to pray in general and were asking Him to teach them is ludicrous. They lived in a praying culture and certainly learned how to pray no later than toddling.