New Covenant Believers, whether Christian or Jew, have access to God through the indwelling Holy Spirit. The common Christian belief that Old Testament Jews had no personal access to God aside from the Cohanim, or Priesthood, is a misunderstanding, if not a slander on both God and His People. God considers Israel to be His wife—does a wife have no way to approach her husband?

While it is true that the OT emphasis was on God’s relationship with corporate Israel, it was never the case that individual Jews were without access to God by means of prayer, sacrifice and Temple worship. Many instances are recorded in Scripture of Jews offering personal prayer directly to God. Think of Hannah, for example, praying daily for a son and in her old age finally being blessed with Samuel. David was King, but had no priestly privileges, yet he was evidently the most prolific prayer warrior of ancient Israel. Solomon, David’s son, offered an elegant prayer in dedication of the new Temple that he built. Daniel, Hananiah, Mishael, and Azariah were all from the tribe of Judah, and God honored their individual prayers in Babylon and Persia. Every Jewish family was required to send a family representative to the Jerusalem Temple of 14 Nisan every year to personally, by his own hand, sacrifice a lamb or kid at the foot of the altar. Jews of any tribe, including women, could enter the inner Court of Israel to bring a sacrifice to the altar when they felt the need. Biblical Ezra himself was instrumental in bringing synagogues, houses of prayer for common folks, to Jerusalem.

It is also not uncommon to hear devout Christian criticism of “Jewish prayer“, usually because it is viewed as “ritualistic” and thus, “Surely it can’t be heartfelt.” I beg to differ. This article is an introduction to Jewish and early Christian prayer life.

Early Synagogues

After successive Babylonian conquests of Judah, most of the Jews who were subsequently resettled in Babylonia were allowed to establish enclaves and worship as they saw fit. Daniel describes life in captivity only as it pertained to a select few from Jewish nobility who were housed in the royal palace and trained to serve in the King’s administration.

Since the Bible is mostly silent about the rest of the captives, Christian tradition tends to forget about all but Daniel, Hananiah, Mishael and Azariah. Many scholars believe that Godly Jewish exiles began congregating in homes, and in all probability that custom morphed into a synagogue system in captivity.

The later development of synagogues within Israel is probably related to Ezra and the events and edicts recorded in Nehemiah 8 – 12. Whatever their true origins, synagogues were eventually built throughout Israel and the Diaspora as a supplement to the rebuilt Temple in Jerusalem.

By around 150 BC, Judaism had splintered into numerous sects. Politically, the Pharisees held a large minority of seats on the Sanhedrin, but otherwise they had little influence within the Temple and its ritual. They were, however, the most popular sect with the common people. They controlled most of the synagogues, and therefore most of Jewish adult education.

Like Christian denominations today, the Pharisees were not monolithic in all their views or practice, yet they were all fundamentally alike in their reverence for the Tanakh (that is, the Torah, the Prophets and the Writings, which together comprise the Old Testament). I may have more to say about Pharisees in a future post, but for now, my stress is on the fact that the synagogues of Jesus’ day and beyond were tied to the teachings of the Pharisees, as is Orthodox Judaism today.

Jesus undoubtedly grew up worshiping in His local synagogue and learning not only from His father, but from sages of the Scribes and Pharisees. Apart from the facts of His own deity, the worldview that He taught after His baptism by John was in all important respects, the worldview of the Pharisees and the Synagogues.

Jesus’ ministry was to “the House of Israel.” He and His followers worshipped in the same ways as other Jews. After His resurrection and ascension, His followers were still Jewish and still met in the synagogues along with their “non-Messianic” Jewish brothers. At the close of Sabbath services, at sundown, the Messianic believers left the synagogues and adjourned to nearby homes to celebrate the Messiah. I agree with Messianic scholar Arthur Fruchtenbaum (Israelology: The Missing Link in Systematic Theology) that this practice is the likely true reason for Christian Sunday worship. The sharing of services in the synagogues continued until the “followers of the Nazarene” were gradually expelled.

Historians generally credit shared Jewish tradition as the single factor that enabled Judaism to persist as a recognizable ethnic culture through conquest, scattering, and thousands of years of persecution and genocide. Jewish prayer is the backbone of that tradition, and it is almost unchanged in Orthodox Judaism today from what it was in the synagogues of Jesus’ day and earlier.

From Synagogue to Church

Jesus and his apostles, including Paul, not only worshipped in the synagogues, but they frequently taught in the synagogues. As mentioned above, the early Christians worshipped as Jews alongside their Jewish friends and families at the synagogue, on Shabbat, then after sundown they adjourned to Christian homes to worship as followers of the Messiah.

Where did they go in the years after they were expelled from the synagogues? They started their own Messianic synagogues! The early “local churches” were patterned, both physically and organizationally, on the Jewish synagogues of the day. Having no Christian Bible, they worshipped from the same Jewish Bible that their Rabbi, Yeshua (Jesus), had taught from. Apart from recognizing the deity of their Rabbi, and meeting on Sunday in order to avoid profanation of the Sabbath, the ritual of their congregational meetings would not have differed substantially from what they had always practiced.

Modern Christians for the most part, lay or otherwise, know almost nothing about prayer or worship customs in general in the 1st Century AD, in the synagogues of either the non-Messianic or the Messianic congregations.

Let me emphasize, for a third time:

The early Church was 100% Jewish and grew out of the synagogues of Judaism, worshiped the Jewish Messiah, and was ultimately taught by a devout and unapologetic Jewish Pharisee named Shaul (names like “Paul” and “Peter” were Greek names for Jewish men who often ministered to the Greek-speaking world). The local churches certainly followed the customs and rituals of Judaism, including its prayer structure.

Until, that is, the Church itself cast off its charter members and their customs! When the non-Jews began to outnumber the Jews, arrogance on both sides caused a rift that still exits.

Prayer in Synagogue and Church

Prayer in the synagogues was mostly ritualized and recited from memory. Jewish believers in the first churches would have certainly continued to pray the same prayers that they had prayed all their lives, plus some new ones, specific to Worship of their newly revealed Messiah.

Informal Prayer

Like faithful modern Christians, faithful Jews also pray often, individually and spontaneously, “from my lips to God’s ears.” That’s not to say without ritual. Sometimes that means wearing a tallit, or prayer shawl, draped over the head like a hood. Sometimes wearing tefilah, ritual boxes on the forehead and the back of one hand. Sometimes shuckling, or rocking forward and backward (there are several reasons for this custom, but think of the flame of a candle). Usually facing towards Jerusalem and the Temple Mount. And always while davening, i.e., moving the lips.

Formal Prayer

Jews from the time of Moses until late in the 2nd Century AD carefully memorized and passed down all aspects of Jewish custom, including worship practices. This was an obligation of every family and school, and though not all were faithful, many did participate. Because so many were memorizing the same things in parallel settings and “comparing notes” with each other, there was little chance for error to creep into the memorized material over all the generations.

When the oral process began to fail after the Roman dispersion, Jewish scholars began a written compilation, the Mishnah, and later the two compilations (Babylonian and Jerusalem) of the Talmud, plus countless additional Rabbinic writings. Because of these meticulous records, we can be very explicit about how the early Jews prayed and how those prayers have changed over the millennia.

Because of the meticulous record-keeping within Judaism, I am confident that Jews today pray much as they did in Jesus’ day, and because early Messianic Judaism was still Judaism and still associated with the synagogue, I am confident that their prayer was much the same.

In the remainder of this post, I’ll be addressing categories of formal prayer that I believe was practiced by 1st Century Jews and Christians.

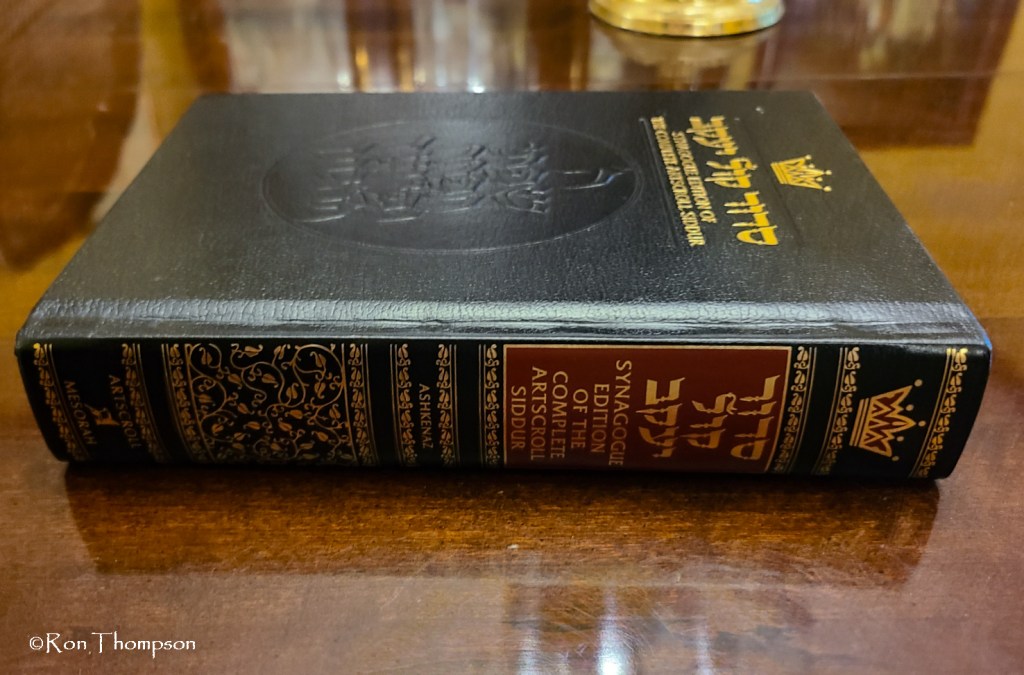

Memorization of spoken ritual was required of non-messianic and messianic Jews in the 1st Century. While some modern Orthodox Jews still memorize vast amounts of information, most now rely on prayer books, or Siddurim (sing. Siddur). Pictured above is an English/Hebrew Siddur prepared for use in English-speaking synagogues. Most Orthodox Jews learn Hebrew, “the holy tongue”, but not all people who attend will understand that language, so Siddurim are often bilingual, with the vernacular either in parallel columns or interlinear.

Corporate Prayer

In today’s Church, corporate prayer usually means one person praying out loud while everyone else in attendance either listens and silently “agrees”—or thinks about other things. Honestly, I’ve never had the focus to follow along very effectively, and I’m too self-conscious to lead. I suppose that’s bad on me, but I’ve adjusted to the reality.

Am I alone? Maybe, but I fear being the hypocrite in:

[5] “When you pray, don’t be like the hypocrites, who love to pray standing in the synagogues and on street corners, so that people can see them. Yes! I tell you, they have their reward already! [6] But you, when you pray, go into your room, close the door, and pray to your Father in secret. Your Father, who sees what is done in secret, will reward you.

—Matthew 6:5–6 (CJB)

All Jews and all synagogues are not alike, but my own experience with the Orthodox is that they don’t like to be singled out for public or even one-on-one prayer. Prayer in the synagogues is focused on praising Hashem (“the Name”, God) and trusting Him to know their needs. To that end, a Rabbi, reader or “cantor” reads from the Siddur and the rest of the congregation lip-syncs or else quietly (moving lips and whispering) reads a responsive portion.

Kavanah

Yes, Jewish religious life is ritualized, but you have only to read the Tanakh (Old Testament) to see that God Himself commanded a great deal of ritual. People being what they are, nobody (including Jews) would deny that for many the recitations become mechanical and devoid of meaning; but this itself is a violation of Jewish law. Before any ritual, a faithful Jew must stop whatever he is doing and center his concentration and desire on God in “awe, fear, trembling and quaking.” The words he recites must represent to him Kavanah, or the “true desire of his heart.”

The Disciples’ Prayer

Was Jesus opposed to ritual prayer? Consider:

[7] “And when you pray, don’t babble on and on like the pagans, who think God will hear them better if they talk a lot. [8] Don’t be like them, because your Father knows what you need before you ask him.

—Matthew 6:7–8 (CJB)

The classic example of this is Elijah’s contest with the priests of Ba’al, who babbled to their god for hours, to no effect (1 Kings 18:26). Jesus’ exhortation to avoid “meaningless repetition” in prayer is certainly not referring to formalized (ritual, if you will) prayer. With His very next breath, He did as many of His contemporary rabbis did: He instituted a ritual prayer specifically for His own followers:

[9] Pray then like this:

“Our Father in heaven,

hallowed be your name.

[10] Your kingdom come,

your will be done,

on earth as it is in heaven.

[11] Give us this day our daily bread,

[12] and forgive us our debts,

as we also have forgiven our debtors.

[13] And lead us not into temptation,

but deliver us from evil.

—Matthew 6:9–13 (ESV)

Most evangelicals look on “The Lord’s Prayer” as merely a pattern, or template, to show the things that are proper in a prayer. That’s fine, I don’t think it need be an important issue for us, but my view is that Jesus’ disciples recited this prayer whenever they met, sort of on the lines of a “Pledge of Allegiance.” Most likely, it is a shortened version of the Amidah (see below).

Grace After Meals

Evangelical Christians are horrified if one of their number hosts a meal without “saying grace” before everyone digs in. If one eats a meal without first saying grace, he or she is “eating like a heathen“. Technically, there is absolutely no Biblical precedent for this Christian tradition. But wait! “Didn’t Jesus bless the food before His Last Supper and before feeding the 5,000?” See the next sections for more on blessings and what Jesus actually did before meals. Grace is a prayer said after eating, to thank God for the sustenance that He has just blessed you with.

Like all other formal Jewish and, I’m confident, early Christian prayer, the format and words for the Grace After Meals (Birkat Hamazon) has a usual, fixed format and wording.

Usual, because there are variations for special meals or for certain days, such as sabbaths, new moons, and feast days. There are also differences based on whether you are Sephardic or Ashkenazi, and slight variations for different sized groups.

Fixed, because the wording for all variations of all formal prayers is read from Siddurim.

Blessings

The prayers that most people associate with Judaism are the “blessings” (Hebrew b’rakhot, sing. b’rakhah). These are short, formulaic, often one-sentence prayers or benedictions that accompany almost anything that a faithful “observant” (practicing) Jew does or consumes during a day. Many begin with all or part of the phrase, “Barukh attah Adonai Eloheynu Melekh-ha‘olam…”, meaning “Blessed are you, Lord our God, King of the Universe…”.

These prayers have a single purpose, to praise God for His provision and watch-care. I’m sure that God honors our prayers, even when we fumble the terminology. And we do! But to ask someone at table to “bless the food” is meaningless. The blessings before eating were not intended to confer holiness or some special property on what we are going to consume. Nor are we asking God to regulate our metabolism to more favorably assimilate the nutrients. Food and drink are what they are, good or bad, and they do what they do, favorable or not. God has already seen to all that. That is why, whenever Jesus broke bread, for example, He said, “Blessed are you, Lord our god, King of the universe, for bringing forth bread from the ground.” We are praising God for what He has already done!

There are b’rakhot (blessings) for everything that a faithful Jew encounters in life, good or bad, minor or of great importance. Don’t believe me?

“Blessed is God who has formed the human body in wisdom and created many orifices and cavities. It is obvious and known before You that if one of them were to be opened or closed incorrectly, it would be impossible to survive and stand before You at all. Blessed is God, who heals all flesh and does wonders.”

—The Asher Yatzar, the “bathroom blessing”

Note the following example from the “Last Supper”, and find the two relevant blessings in the photo above:

[26] While they were eating, Yeshua [Jesus] took a piece of matzah [unleavened bread], made the b’rakhah [blessing], broke it, gave it to the talmidim [disciples] … [27] Also he took a cup of wine, made the b’rakhah, and gave it to them…

—Matthew 26:26–27 (CJB)

Daily Prayers

Jewish law obligates the Orthodox to pray at least three times a day. Many choose to gather at the synagogues for this as often as practical. The three formal prayer times are frequently referred to in Scripture. They consist of the morning (shacharit) prayers, the afternoon (minchah) prayers, and the evening (arvith or maariv) prayers.

The Sh’ma

The Sh’ma is the central affirmation of Judaism, and is cited twice a day, at the morning and afternoon prayers. Hopefully most Christians will recognize the preamble, as translated, “Hear, O Israel, God is our Lord, God is One.” The full text of the Sh’ma consists of three passages: Deuteronomy 6:4–9, Deuteronomy 11:13–21 and Numbers 15:37–41.

The Amidah

Another prayer that is obligatory, in some format, at all three daily services, and more often on some Holy Days, is the Amidah (lit., “standing”); also known as the “Standing Prayer”; also called the Shemoneh Esrei (“Eighteen”), because it originally consisted of 18 “benedictions”. During the Roman period, sometime after AD 70, a 19th benediction was inserted near the middle, as number 12 (highlighted in the “table of contents” below).

The added benediction is interesting, because it was in part added to “put a hex” on Christianity. One form, quoted in the Jerusalem Talmud, Benediction 12, the so-called Birkat haMinim (lit., “Blessing on the heretics”, though in reality it is a curse), reads as follows:

For the apostates (meshumaddim) let there be no hope,

and uproot the kingdom of arrogance (malkhut zadon), speedily and in our days.

May the Nazarenes (ha-naẓarim/noṣrim/notzrim) and the sectarians (minim) perish as in a moment.

Let them be blotted out of the book of life, and not be written together with the righteous.

You are praised, O Lord, who subdues the arrogant.

My personal opinion is that it is unlikely that this was added before the Bar Kochba Revolt of AD 132–136. During the First Jewish/Roman War (AD 66–73) and the Kitos War (AD 115–117), Christians joined forces with their non-Messianic brothers to fight the hated Romans. But when Simeon Bar Kochba (Simon Bar Koseba) led Jewish forces against the Romans, the sage Rabbi Akiva proclaimed him to be the Messiah. This posed an insoluble moral dilemma to the Christians, who then chose to stand down. The result was that prior decades of deteriorating relations suddenly became a decisive split.

Conclusion

This is just a smattering of information about a vast subject—the Jewish foundations of Christianity. Though my own interests vary widely, my principal goal during much of my life as an adult Christian has been to illuminate the debt that Christianity owes to its Jewish beginnings.

I am not advocating that Christian churches should go back to 1st Century ways of worshipping! I simply want to point out our beginnings and caution against judging ancient Jewish customs by anachronistic standards.