Some notes on hermeneutics

“When the plain sense of Scripture makes common sense, seek no other sense; therefore, take every word at its primary, ordinary, usual, literal meaning unless the facts of the immediate context, studied in the light of related passages and axiomatic and fundamental truths, indicate clearly otherwise.”

–Dr. David L. Cooper (1886-1965),

founder of The Biblical Research Society

The above quote is known by many expositors as “The Golden Rule of Biblical Interpretation.” BibleTruths.org states that, “This has often been shortened to ‘When the plain sense of Scripture makes common sense, seek no other sense, lest it result in nonsense.’” An implication of this rule, which I think is inescapable, is that not every word of Scripture is meant to be understood literally. That is troubling to many, because in careless or untrained hands it opens the door to subjectivism and arbitrary conclusions. Yet almost all the great conservative Bible commentators practice a hermeneutic (a set of formal principles for Biblical interpretation) that allows for non-literal text, including parables, figures of speech, anthropomorphism, poetic exaggeration, and a host of other confusing factors. Not to mention translational difficulties. Understanding the “genre” (from the Latin genus), or “literary type” of a Biblical passage is one obvious prerequisite for understanding how literally one should interpret it.

Suggesting that some passages should probably not be understood in a literal sense does not subtract from the central truth that “all Scripture is God-breathed.” It is axiomatic to me that the Bible is inerrant in its original language and the original manuscripts. Yet some folks read my opinions, especially respecting emotional themes like creation, and make snide comments like, “So you believe it’s inerrant except when it isn’t!”

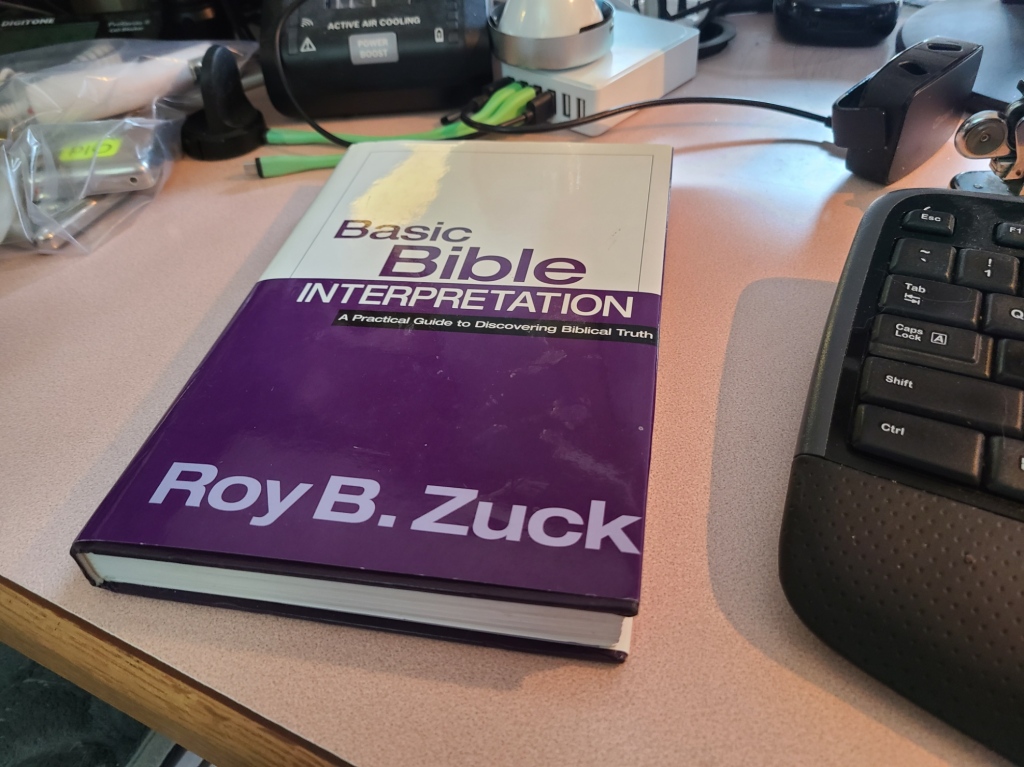

My suggestion for anyone who wants to understand Scripture for himself or herself, or to judge the competence of another commentator, is to read a good book on hermeneutics. One that I recommend is Basic Bible Interpretation: A Practical Guide to Discovering Biblical Truth, ©Roy B. Zuck, 1991. I pretty much agree with all of Dr. Zuck’s stated principles, though I am not in full agreement with some of the applications he makes from his interpretations. For example, he and I are not on the same page with respect to Covenants and Dispensations.

I don’t think there are any substantive problems with corruption of our Scriptures over the millennia. There are a few problems with translation, but none that are impossible to unravel with sufficient attention to the linguistic and cultural background of the humans who penned the words, and those who the words are written to.

What I consider to be the biggest factor of all that contributes to doctrinal confusion and infighting in the Church is that some misinterpretations are enshrined in a nearly impenetrable wall of tradition.

In the remainder of this post, I am going to discuss three books in the Tanach, or Old Testament that I believe contain a mixture of literal and metaphorical text. Some of my readers will disagree with me about Job. Most will agree with me about Ezekiel, at least in general terms. Probably only a few will agree with me about Genesis.

The genres of Job

The book of Job is classified as “reflective wisdom literature” overall, but within the book, scholars recognize two, more specific, genres: Chapters 1, 2, and verses 7–16 of the final chapter, 42, are narrative, while the rest of the book is poetic.

Per Zuck, a Biblical narrative is a “story told for the purpose of conveying a message through people and their problems and situations.” The story is typically selective and illustrative, meaning that it doesn’t necessarily quote conversations verbatim or events in chronological order. Only substantive elements that contribute to the illustration are included. This is why, for example, the narrative content of the different Gospels differs somewhat from book to book when describing the same event. The separate human authors, under the same inspiration, often used different words to stress different aspects. Matthew and Luke report two Gadarene demoniacs, for instance, while Mark mentions only one, and John omits the incident entirely. Why only one in Mark? Because only one of them obeyed Jesus by telling his countrymen about the miracle of his exorcism and preparing the way for Jesus’ return to the region later in the book. The second man was inconsequential to the lesson Mark wished to teach.

Literate readers of our time have hopefully been taught a rigid set of literary rules for grammar and punctuation, but trying to hold ancient writers to the same standards is an anachronism. Thus, we must not be offended when quotations are loose, numbers are approximate, and chronology is fluid. In no ways do these things detract from the authority of Scripture.

When reading the narrative portions at the beginning and end of Job, we can be sure that there is no error in the substance of the story. What the words convey are substantially true, and the lesson they convey is unambiguous.

Leaving the narrative portions, the bulk of Job is poetic. Hebrew poetry has a very recognizable style of its own that some people find hard to follow. Rhyme and meter in the Hebrew originals cannot be transferred intact to English translations, but there is usually recognizable structure. One common element that we frequently see is two or more lines that state the same thing, but in different words. This rephrasing is called parallelism.

Biblical poetry is less exact than Biblical narrative, because the language of poetry is more flowery and sometimes exaggerated or hyperbolic. The narrative within the poem is much less important than the lesson taught by the poem. In my opinion it is dangerous to base dogma on poetic Scripture. Take, for example:

13 ¶ to him who split apart the Sea of Suf,

for his grace continues forever;

14 and made Isra’el cross right through it,

for his grace continues forever;

15 but swept Pharaoh and his army into the Sea of Suf,

for his grace continues forever;

—Psalm 136:13–15 CJB

Psalm 136 is an antiphonal song, during which a cantor might have sung or chanted the first line of each verse and a choir of Levites the second. Its intent was to praise Almighty God, and any details included here that were not recorded in the Torah writings could conceivably be embellishment. Exodus does not state that Pharaoh drowned in the Sea (The Reed, or Red Sea), and my analysis (see Historic Anchors for Israel in Egypt) indicates that he did not. Furthermore, “swept Pharaoh and his army into the Sea” clearly contradicts the Exodus account. The Egyptian army followed the Israelites into the sea and the sea swept across them.

In the case of Job’s poetry, the important lessons have to do with God, His power, and His relationship to His creation. The conversations between the actors here (between Job and his wife and friends, or even the conversations between Job and God) were immaterial aside from their message and need not have been quoted exactly as literally spoken.

The genres of Ezekiel

Ezekiel is probably my favorite book in the Bible. It is a great illustration of the “prophetic” literary genre, and it may be the best example in Scripture of narrative and poetic symbolism.

What is prophecy? I think it is a message about the past, present, or future that is supernaturally delivered by God to His people through the agency of one or more of His people who are empowered by Him to act as His intermediary. I don’t think that there are any prophets today, though there will be again as the present age comes to a final end. There were no prophets after Micah until John the Baptizer. There have been none since the death of the Biblical apostles. Some Bible teachers will claim that today’s pastors and evangelists are prophets, by definition, but I don’t believe that the common leading of the Holy Spirit, which is often hard to distinguish from personal volition, counts. For one to feel like he is led by the spirit is nice, but not provable. Fallen humans should not revel in such feelings.

Ezekiel’s prophecies were mostly imparted to him by means of visions, and mostly passed on either through acting out skits (object lessons) or verbally. When verbal, and as recorded in Scripture, some were in narrative form, and some were poetic.

Ezekiel’s vision of God and heaven at the beginning of the book represent his impressions of whatever he actually saw. Efforts to interpret what he described in meaningful visual terms are fruitless. What I think we are supposed to see is that God is holy, majestic, and humanly beyond accurate description.

In chapters 4–32, Ezekiel presents a series of skits and sermons that call out the sins of Israel and other nations of the day and pronounce condemnation and judgement for those sins. Though he uses a mixture of plain language and symbolism, the unity of the message is clear.

Beginning with Chapter 33 we start seeing the beginnings of future restoration, culminating in the defeat of Gog and Magog in Chapters 38 and 39 (see my post, The Coming World War: Gog and Magog).

Finally, chapters 40–48 forecast events and objects in the Messianic age. Some of this material regards the return of God’s sh’kinah “presence” to the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. Previously, in chapters 10 and 11, Ezekiel described the departure of the sh’kinah from Solomon’s Temple immediately prior to its destruction by Nebuchadrezzar in 586 BC. The return of sh’kinah will be specifically to the Holy of Holies in the new Millennial Temple, which will be built on a radically different landscape at the same geographic location. I discuss my own exegesis (interpretation and analysis) of both the departure and return in the question-and-answer section near the end of my post, Opening the Golden Gate. That post also summarizes the history of the Temple in its different phases of construction. Contrary to what is believed by most Christians, both lay and ordained, it was the Father, not Jesus the Son, who will enter the Temple—and not through the Eastern Gate, but over it. The genre of both passages is prophetic narrative, and entirely symbolic, though with important theological meaning and at a location which is certainly literal. In theological terms, God in His immanence may have abandoned the Temple and the people of Israel, but in transcendence, He has always been with them.

the genres of Genesis

The five “Books of Moses“, often called Torah (Hebrew, not for “law”, but rather for “teachings”), or sometimes Chumash (my own default, Heb. “five”) or Pentateuch (Greek “five vessels, or containers”) are attributed by conservative scholars to Moses; a view that I share. They include to some extent, all genres of Hebrew literature.

Genesis, in particular, is largely narrative in style, as you might guess. It also includes a small amount of poetry. I suggest that all of it, from beginning to end, is also prophetic in nature. Israel has always, since the Exodus from Egypt, considered Moses to be the greatest of the prophets. But I don’t recall ever hearing it suggested explicitly that his knowledge of preexilic history was prophetically derived. Certainly, it was! Recall that I implied above that the prophets, through supernatural means, saw events from their past, present and future, through the eyes of God. In a very real sense, that is what “inspiration by the Holy Spirit” really is.

In Genesis 1:1, Moses declared that, in the beginning (Reꜥshit, “first in time, order or rank”), God created (bara, to create ex nihilo, out of nothing whatsoever, which only God can do) the heavens (shamayim, plural, encompassing the air around us, the atmosphere above us, and the vastness of space) and the earth. The phrase “heavens and earth” in Scripture is a figure of speech called a “merism“, in which the totality of something is implied by substitution of two contrasting or opposite parts.

A more complete description of the genre of this one verse is “polemic prophetic narrative”. Every ancient civilization had a pantheon of pagan “gods”, and with each of those came a “creation myth.” In Genesis 1:1, the one true God said, “I did it—not them! Period!”

Theologically, that is really all we need to know about creation. God had no obligation to tell us exactly how he did it, or in what order, and if He had done so, nobody in the ancient world could have possibly understood it. Sure, I’m curious, but God said it, I believe it, and that’s the end of the story!

By the time verse 2 rolled around, the earth had been inundated for some reason. I will discuss that, and my interpretation of the rest of the chapter, in a future post. For now, I’ll simply refer back to the quotation at the top of this post, and say that, to me, the “Plain sense” of Genesis 1:1–2 make perfect “common sense” in a book about God: creation, passage of time, cataclysmic flood, and beginning of a new age. The plain sense of Genesis 1:3–31 does not make common sense to me, if indeed it describes creation at all. To me, it is strongly reminiscent of visions recorded by a number of prophets, including John. The age of man on earth starts with a vision and ends with a vision!

1. The general, (or ‘masculine’) cosmos and the special (or ‘feminine’) Earth (Genesis 1:1).

2. The Earth, as its own general subject, implying that which we all intuit is most valuable about the Earth unto itself in all the cosmos: its abiding maximal abundance of open liquid water (Genesis 1:2).

3. that water and its special relation to the Sun’s light, hence the water cycle (vs. 3-10);

4. The water cycle and its special beneficiary and member, biology (vs. 11-12);

5. biology and its special category, animal biology (plant/animal/mineral = animal) (vs. 20-22, 24-25);

6. Animal biology and its special category, human (vs. 26-28);

7. The general man and the special woman (Genesis 2:21-23).