Christianity has traditionally viewed the Pharisees as a uniformly treacherous and hateful group of hypocrites.

There is a marked tendency among some to despise Judaism as a whole for producing such a “reprobate” sect. An Internet search for “Pharisees” turns up almost exclusively sites that range from mildly to bitterly critical. The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines “pharisaical” as an adjective meaning, “marked by hypocritical censorious self-righteousness.” Their Collegiate Thesaurus lists the synonyms, “hypocritical, canting, Pecksniffian [look it up], pharisaic, sanctimonious, [and] self-righteous.” But do they deserve the bad rep?

Personally, I don’t think so!

Pharisee History

According to Josephus, there were only about 6,000 Pharisees during the reign of Herod the Great, and that is unlikely to have changed much during Jesus’ lifetime.

The name “Pharisee” comes from the Hebrew Parush (pl. P’rushim), meaning “separated.” This term refers to their opposition to “the mingling”, that is, the mixing of Greek ideas into Biblical Judaism (which, incidentally, has also been the scourge of Christianity). It is believed by many scholars that the Pharisees were spiritual descendants of the Chasidim (“pious ones”), a devout group of scribes dedicated to the preservation of the written and oral Torah during and after the Babylonian Captivity.

The first clear historical references to the Pharisees occurred in the Intertestamental period (between the Old and New Testament writings), during the reign of John Hyrcanus (134–104 BC). By then, they had formed into an elite religious society, or order, with limited membership and strict rules of conduct. They had gained wide popular support due to their opposition to Hellenism (Greek culture), the rise of the corrupt Sadducees, and the illegal high priesthood of the Hasmonean monarchs. Despite their popularity in the synagogues, their political influence was very limited at first.

Accused of fostering revolt, as many as 800 Pharisees were crucified by Alexander Jannaeus (108–76 BC). During the reign of Queen Alexandra Salome (76–67 BC), whose brother was a Pharisee, they finally gained considerable power. Unlike the Sadducees, they never welcomed Roman rule, but they were able to maintain some influence, only because they were willing to cooperate in order to maintain peace and stability.

During the Roman period, spanning the life of Herod the Great and the 1st Century AD up to the destruction of the Temple in AD 70, the Pharisees were highly influential with the populace as a whole, though it was the Sadducees who controlled the Temple and its ritual.

After the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple in AD 70, most Jewish sectarian orders disappeared, but many of the Pharisees were allowed to relocate to Jamnia (Yavneh), on the coast west of Jerusalem, where they formed the nucleus of the great Rabbinic movement of the following centuries.

Sect, or Order?

It is common to call the Pharisees a sect, but that term is misleading.

By definition, a sect is an offshoot of a larger religion, or a group sharing distinctive political and/or religious beliefs.

I would term the Pharisees, Sadducees, Essenes, and others as orders. An order is a formal group set apart within their religion by adherence to a particular rule or set of principles. The scribes, on the other hand, were not a religious order. As professionals, they probably belonged to a guild.

1st Century Judaism, as today, was highly sectarian. A majority of the Jewish population of Judea and Galilee probably would have said that they were followers of the Pharisees, that is, adherents of the Pharisee belief system, but to actually be a Pharisee—a member of the Order—required a difficult period of training, and then a formal ordination.

Torah

The Hebrew term Torah rightly translated means, not “law”, but “teachings.” The teachings of Torah do include legal precepts, of course, but those precepts are more about the nature and will of God than about legislation. Even to a Pharisee!

The Pharisees, like Rabbinic Judaism for the last 2,000 years, believed that Torah has two parts: written and oral.

Torah Shebichtav, the Written Torah

The written Torah itself is embodied in books or scrolls. The term primarily applies to the five Books of Moses. These writings individually or collectively are sometimes referred to by Jews as the Chumash (“one fifth”). I personally avoid the Greek term, “Pentateuch.”

To the Sadducees, only the five Books of Moses were Scripture. The Pharisees regarded as holy the entire Tanakh (the OT), consisting of Torah, Nevi’im (the Prophets) and Ketuvim (Writings, sometimes referred to by Jesus simply as the Psalms).

[44] Yeshua said to them, “This is what I meant when I was still with you and told you that everything written about me in the Torah of Moshe, the Prophets and the Psalms had to be fulfilled.” [45] Then he opened their minds, so that they could understand the Tanakh…

—Luke 24:44–45 (CJB)

Torah Sheba’al Peh, the Oral Torah

The “Written Torah” was transcribed by Moses “from the mouth of the Almighty” and is contained within the Torah scroll. The “Oral Torah” incorporates the traditions handed down from Sinai but not (initially) put in writing, as well as the interpretations and rulings formulated by the sages of each generation.

—TheRebbe.org

The Pharisees taught that Moses received additional teachings on Mt. Sinai that he was not told to write down. Originally this “Oral Torah” was transmitted from father to son and from teacher to disciple. It consisted of additional instructions and rulings to clarify and quantify the written Torah; principles for exegesis of Torah; and authorization for the rabbis to protect the word of the Torah through making Gezayrot, or edicts, as conditions warrant.

Aside from famously criticizing “traditions of the Elders” that contradicted the letter or the spirit of the Written Torah, Jesus never spoke against the Oral Torah as a whole, and in fact He and His disciples were meticulous about obeying the precepts of both Written and Oral Torah. The formal right of the Scribes and Pharisees to administer Torah through interpretations and edicts (see above) was known as “binding and loosing” (prohibiting and permitting) and was believed to have the blessing of God and His Divine Council in heaven. Shortly before his crucifixion, Jesus endorsed this practice when He extended it to His apostles:

[18] Truly, I say to you, whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven.

—Matthew 18:18 (ESV)

Approximately 1800 years ago, Rabbi Judah the Prince concluded that because of all the “travails of Exile”, the Oral Torah would be forgotten if it was not recorded on paper. He therefore assembled the scholars of his generation and compiled the Mishnah, a written collection of all the oral teachings.

The Sanhedrin

The Biblical basis for the Sanhedrin was:

[18] “You are to appoint judges and officers for all your gates [in the cities ADONAI your God is giving you, tribe by tribe; and they are to judge the people with righteous judgment. [19] You are not to distort justice or show favoritism, and you are not to accept a bribe, for a gift blinds the eyes of the wise and twists the words of even the upright. [20] Justice, only justice, you must pursue; so that you will live and inherit the land ADONAI your God is giving you.

—Deuteronomy 16:18–20 (CJB)

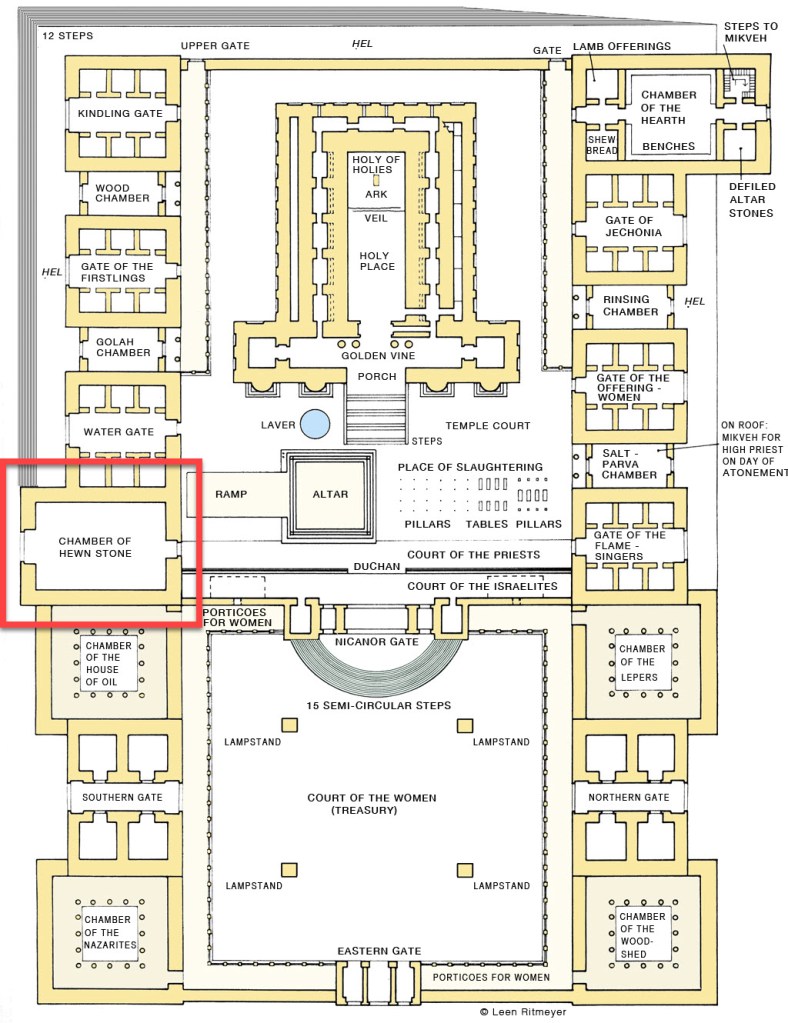

Each major city was ruled by its own political and judicial “Lesser Sanhedrin” of 23 members. Under the monarchy, a “Greater Sanhedrin” was established at Jerusalem to serve as high court of justice and supreme governmental council.

This council at Jerusalem consisted of 71 members, of which the presiding member was the nasi (“prince”, or president), often the High Priest. Membership was appointed, with theological scholarship nominally the basic requirement—but in Roman times, politics effected all major appointments.

According to the synoptic Gospels, Sanhedrin membership consisted of “chief priests, elders, and scribes.” Although there was overlap between those three groups, the chief priests were high ranking Temple priests, mainly members of the Sadducee order; the elders were most likely prestigious Pharisees; and the scribes were respected professionals who might have belonged to any particular order, or to none at all. The Gospel of John mentions only Pharisees and scribes from the Sanhedrin, but when John wrote, probably around AD 80, the Sadducees, the Sanhedrin and the Temple were long gone and a distant memory to his readers.

Pharisees as Sanhedrin Agents

The Pharisees in Jesus’ day were scattered throughout Judea and Galilee, with concentrations in the cities. Many were attached to specific synagogues, while others adopted the life of itinerant teachers, doing much the same things as Jesus. Many of these, perhaps a large majority, were no doubt still Godly men like the first Pharisees, out of the spotlight and unconcerned with politics and wealth. Certainly, when Jesus crossed paths with these men, there were discussions and perhaps even confrontations. I have witnessed brash conversations between Jewish intellectuals in my own day, and I don’t think that it would have been any different then than now.

But what about the Pharisees and scribes that followed Jesus around from town to town? The late David Stern, translator of the Complete Jewish Bible, wrote frequently in his own books and commentaries that these men were probably on assignment from the Sanhedrin. One of the duties of that body was to investigate not only claims of heresy, but also claims of messiahship. Since priests and Levites on the council were mostly Sadducees, who did not believe in a coming messiah, this duty would naturally fall to Pharisees and their scribes. Some would have been belligerent, others merely inquisitive.

Some members of the Sanhedrin were Godly men (e.g., Nicodemus and Gamaliel), but many others were corrupt—collaborators, greedy for wealth and power, and jealous of their position. I believe that the “committee” following Jesus probably consisted of both types. Perhaps it was the same handful of men that we see Jesus arguing with over and over again. Can it be that whenever Jesus blasted the Pharisees, it was “those Pharisees from the Sanhedrin” that He was speaking of—not all Pharisees in General?

Core Beliefs of the Pharisees

Despite the impressions one often receives in reading of Jesus’ frequent confrontations with the Pharisees, He seldom disputed with them on points of doctrine. The Pharisees revered God’s Holy Word and were strongly committed to daily application and observance of its precepts.

They believed in resurrection, immortality, divine judgment, angels, and spirits. They looked for a coming messiah and took responsibility for evaluating claimants. They believed in God’s intervention in human affairs. Many things, they believed, are predestined; human will has only limited freedom within the sovereign will of God.

In Mt 23:1-3 (see below), Jesus is telling the followers of the Pharisees, in effect, “Do what they say, but not what they do.” The reference to “Moses’ seat” speaks literally of the customary seats in the synagogues that were occupied by the teacher during formal Torah studies, but I think it also implies an acknowledgement by Jesus of their historical authority to teach the truths of Torah.

Jesus’ Debates with Pharisees

I am sure that you have heard it said that Jesus “turned the ancient world upside down with His new commandments and interpretations of scripture.” Certainly, He provided many new insights in the area of prophetic interpretation and fulfillment, but in my opinion He actually presented little or nothing new in the way of doctrine, because the doctrine He taught was already imbedded in the Tanach; rather, He set the record straight on issues that had been clouded by denominationalism, and He turned the clock back on corrupt, or at best legalistic trends that had developed within Jewish society.

Though the great sages of the Pharisees were in substantial agreement with each other on most doctrinal issues, they did, however, often disagree on certain points of interpretation or application. When we see Jesus arguing with a Pharisee, what He is doing most often is simply taking sides in these disagreements. For example, the issues discussed in the so-called “antitheses” of Mt 5:21–48 had been the subject of hot debate among the sages, particularly the rival houses, Beit Hillel and Beit Shammai. Jesus was not presenting new doctrine, but rather pronouncing on these issues from the perspective of His divine authority.

If one can believe the Jewish literature of the Rabbinic age (and I think that most of it is trustworthy), almost everything that Jesus said had been previously said in some form by earlier Jewish sages. Some Christian scholars would claim that the rabbis plagiarized Jesus’ remarks, falsely attributing them to their own heroes. Of course, “critical scholarship” would say it was Jesus who plagiarized. My take is this: God’s truths are timeless and unchanging. God always has a remnant on the scene to expound that truth.

Because of God’s love and grace, He always “prepares the ground” ahead of the sower. Jesus did not arrive on the scene with a Gospel that was radically new and unacceptable to his Father’s chosen people. His path had been prepared in advance by the Pharisees, though ultimately most rejected Him.

As an engineer, I was taught that a good technical paper should have three parts: (a) tell ‘em what you’re going to tell ‘em; (b) tell it to ‘em; and (c) tell ‘em what you told ‘em. In this case, the Pharisees did (a), Jesus did (b) and the New Testament writers did (c).

How did the Pharisees See Themselves?

The Rabbinical descendants of the Pharisees tackled this question in both versions (Babylonian and Jerusalem) of the Talmud. Both list the following Seven Kinds of a Pharisee, in very similar terms:

- The “shoulder” Pharisee, who wears his good deeds on his shoulders and obeys the precept of the Law, not from principle, but from expediency.

- The “wait-a-little” Pharisee, who begs for time in order to perform a meritorious action.

- The “bleeding” Pharisee, who in his eagerness to avoid looking on a woman shuts his eyes and so bruises himself to bleeding by stumbling against a wall.

- The “painted” Pharisee, who advertises his holiness lest anyone should touch him so that he should be defiled.

- The “reckoning” Pharisee, who is always saying “What duty must I do to balance any unpalatable duty which I have neglected?”

- The “fearing” Pharisee, whose relation to God is one merely of trembling awe.

- The Pharisee from “love.”

—International Standard Bible Encyclopedia

Certainly, one can find examples of each type of Pharisee in scripture. Note that only the “Pharisee from love” was considered by the later Rabbis to be a truly Godly man.

My Conclusions

Unfortunately, by Jesus’ day, many (but certainly not all, and probably not a majority) of the Pharisees and scribes had in fact succumbed to a legalistic form of worship. Where before they had kept Torah out of a deep zeal to obey God’s commands, now many began to define their spirituality not by their love but by a prideful tally of their good deeds.

[23:1] Then Jesus said to the crowds and to his disciples, [2] “The scribes and the Pharisees sit on Moses’ seat, [3] so do and observe whatever they tell you, but not the works they do. For they preach, but do not practice.

—Matthew 23:1–3 (ESV) emphasis mine

What I am suggesting here is that you reconsider your attitude towards the Pharisees—to see them not as an evil cult that brought on the ruination of the Jewish people, but rather as a powerful spiritual force that bridged the gap between Ezra, Nehemiah and the latter prophets, and the arrival of Messiah.