Originally published in three parts in March 2013

- Myth: The resurrection occurred on Easter Sunday

- Myth: The crucifixion occurred on Passover, Nisan 14

- Myth: Jesus died at the very instant that the High Priest plunged his knife into the heart of the Passover Lamb

- Myth: The crucifixion actually took place on a Wednesday

- Myth: By dying on Passover, Jesus became our Passover Lamb

- Myth: As our Passover Lamb, Jesus brought salvation to the world

- Myth: Peter accidentally cut off Malchus’ ear while taking a wild swing with his sword in an effort to protect Jesus

If you think I’m about to say that the resurrection is a myth, forget it! The resurrection of Jesus is central to my life and theology. I’d have no reason to exist without it. This is about “other stuff.”

Myth: The resurrection occurred on Easter Sunday

This won’t come as a shock. We all know that Easter is a Christian commemoration of the event, not a celebration of the exact day of the year. But why do we do it that way? In the early centuries of Christianity, many churches in the Roman Empire began to object to celebration on the traditional date, considering it to be a “humiliating subjection to the Synagogue.” During the 2nd Century, many of those churches had begun celebrating Easter on a Sunday, regardless of the Biblical calendar. For a clue to the mindset, there’s this ancient text: “Sunday commemorates the resurrection of the lord, the victory over the Jews.” (Emphasis mine)

In AD 325, Emperor Constantine convened the Council of Nicaea to discuss two major issues in the church. One of those was “the Passover Controversy”, the disagreement between churches that commemorated the resurrection on the Jewish feast day and those that did not. Constantine’s view, of course, won out. He wrote,

It seemed to every one a most unworthy thing that we should follow the custom of the Jews in the celebration of this most holy solemnity, who, polluted wretches! Having stained their hands with a nefarious crime, are justly blinded in their minds.

It is fit, therefore, that, rejecting the practice of this people, we should perpetuate to all future ages the celebration of this rite, in a more legitimate order, which we have kept from the first day of our Lord’s passion even to the present times. Let us then have nothing in common with the most hostile rabble of the Jews. … In pursuing this course with a unanimous consent, let us withdraw ourselves, my much honored brethren, from that most odious fellowship. … [I urge you] to use every means, that the purity of your minds may not be affected by a conformity in any thing with the customs of the vilest of mankind. … As it is necessary that this fault should be so amended that we may have nothing in common with the usage of these parricides and murderers of our Lord.

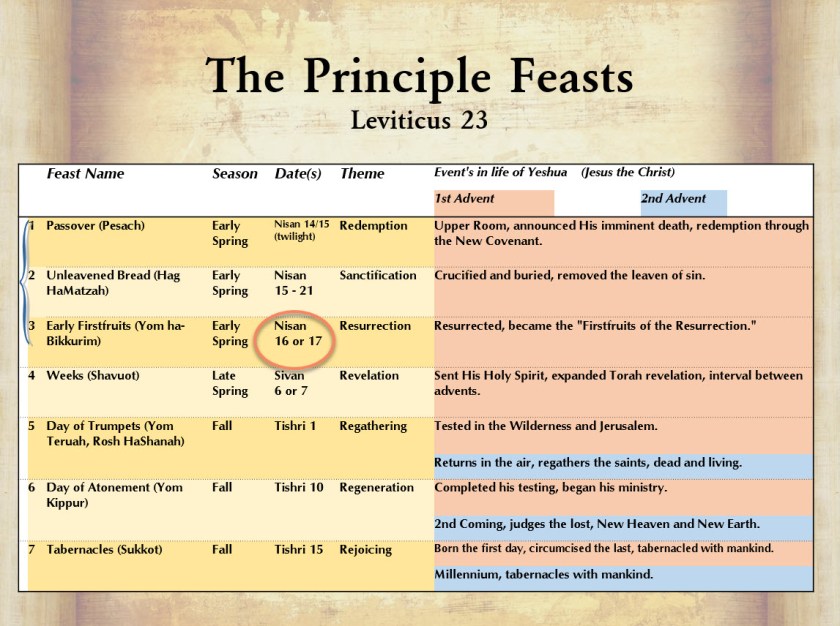

The date for Jewish celebration of the Passover season Feasts is tied by Divine Ordinance to specific dates on the Hebrew calendar (see Leviticus 23). Non-Jews are released from such ordinances, so I don’t care on what day we celebrate the Resurrection. But you should be aware that the name, “Easter”, and most of the secular traditions tied to the holiday are pagan in origin, and that the Nicene Council separated it from Passover for blatantly anti-Semitic reasons.

Myth: The crucifixion occurred on Passover, Nisan 14

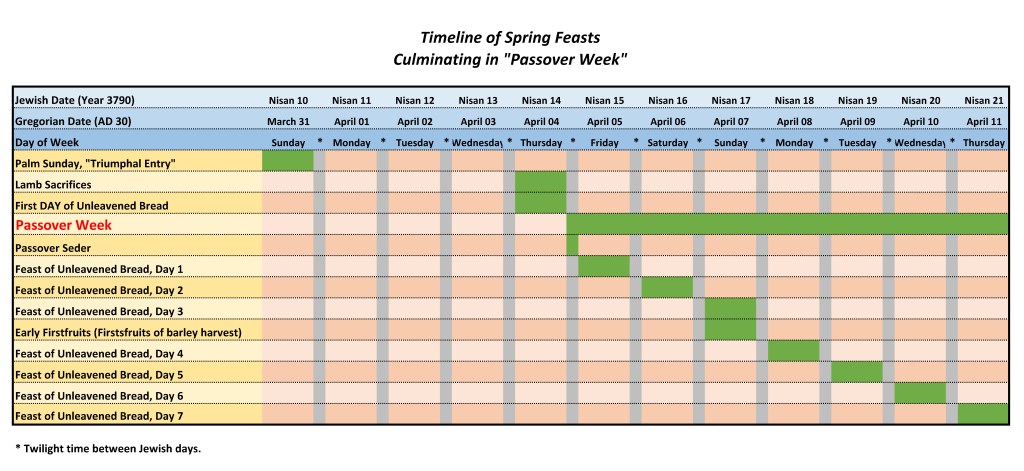

Well, yes and no. The crucifixion happened on Nisan 15, after the sacrifices and after the official Passover as specified in Torah. It became customary, even within the pages of the New Testament, to refer to the three spring feasts together as “Passover.” Technically, Passover is just the short period of twilight between Nisan 14 and 15, on the Jewish calendar (see Part 2 of this series). Immediately after this interval, the 7-day Feast of Unleavened Bread begins—on Nisan 15. And in the middle of this 7-day period, there is the Feast of Early Firstfruits. Jesus’ Last Supper was a Passover Seder. That meal always begins during that twilight period, true Passover, and ends around midnight on Nisan 15, when celebrants adjourn to the streets and rooftops to sing the Hallel Psalms together. The crucifixion, therefore, occurred on Nisan 15, the first day of the Feast of Unleavened Bread.

Myth: Jesus died at the very instant that the High Priest plunged his knife into the heart of the Passover Lamb

I’ve heard this one even from Ray Vander Laan, a man I consider to be an expert on Israel and its customs, in his series of videos for Focus on the Family. But it’s wrong on so many levels! First, the sacrifices occurred during the day before the Seder, on Nisan 14; the crucifixion was the next day, Nisan 15. Second, there wasn’t just one lamb; there was a lamb for approximately every ten people celebrating. Perhaps 100,000 lambs, killed over a period of hours! Which one are they talking about? Third, the High Priest killed only his own lamb, and that much earlier in the day, before the Temple gates were opened. All the other lambs had to be killed by their owners, not by a priest. Fourth, each lamb was killed by a quick slash of its throat, as specified by scripture. A knife to its heart would be considered cruelty, and in the context of the Feast, could get one stoned. Sometimes, the melodrama in the pulpit is just crazy!

Myth: The crucifixion actually took place on a Wednesday

For two thousand years, most Biblical historians and scholars have held to a Friday crucifixion. More recently, though, many evangelicals have begun to teach that Jesus died on a Wednesday or Thursday. At the heart of this matter is Jesus’ statement in Matthew 12:39–40:

But he answered them, “An evil and adulterous generation seeks for a sign, but no sign will be given to it except the sign of the prophet Jonah.

For just as Jonah was three days and three nights in the belly of the great fish, so will the Son of Man be three days and three nights in the heart of the earth.

—Matthew 12:39–40 ESV

For some reason, it’s hard for some folks to see how you can find three nights between Friday and Sunday! I’m going to present the actual timeline (below, but see also the first chart, above), as I see it, and then I’ll explain several important concepts:

As most Biblically educated people know, prophets often used the word “day” (Heb. yom) to indicate a long or indeterminate period of time, rather than a literal 24-hour solar day. The key to understanding the timing issue here lies in Hebrew idiom—figures of speech. Where there was a likelihood of confusion, ancient Hebrew writers used terms like “three days and three nights” and “the evening and the morning were the first day” to emphasize that true solar days or portions of literal days were in view, not a longer prophetic period of time.

In the Matthew 12 passage quoted above, Jesus was prophesying. Many of His listeners believed in a coming resurrection of the dead in the acharit hyamim, or end times, so it was necessary for Him to emphasize that He was speaking of something that He would personally experience, and that it would be of short duration. Paraphrased, He was saying, “In a little while, I’m outta’ here, but I’ll be back before you know it, on the third calendar day.”

In both spoken and written Hebrew, references to literal solar “days” or “days and nights” did not necessarily imply that complete 24-hour periods were meant. “Three days and three nights” meant “some part of one solar day, all of a second, and some part of a third.” On the first line of the second timeline chart above, “Day 1” was Friday. Recall that Jewish days last from evening twilight until the subsequent evening twilight (see the third chart, below). Jesus died around 3 PM and was entombed before twilight, so at most He was dead only around three hours on this day. He remained in the tomb all through the night and day of Saturday, “Day 2”. His resurrection was sometime on Sunday morning, “Day 3”, before His tomb was found open. The total period was thus composed of a little more than one full period of daylight and at most two full periods of dark. “Three days and three nights” by traditional Hebrew reckoning.

Many conservatives refuse to believe this non-literal interpretation of Jesus’ words and insist on exactly 72 hours, but the hermeneutic employed by me and many conservative, Evangelical scholars allows for a non-literal (but not random!) interpretation of various obvious (to those who understand Hebrew literary techniques) figures of speech.

Many well-meant attempts to rescue the Friday crucifixion tradition resort to various forms of Greek linguistic gymnastics, trying to prove that “in the heart of the earth” doesn’t really mean buried, but could, for example, mean the period from Jesus’ betrayal to His resurrection. I urge caution in using Greek to understand Hebrew concepts. Hebrew idiom does not always translate well into Greek.

Each Jewish day begins at nightfall and lasts until the following sundown. The twilight period between any two days technically does not belong exclusively to either day, or in another sense, it can be viewed as belonging to both days. The Seder supper always begins during this twilight period between Nisan 14 and Nisan 15 (see Lev 23:5). Note that the lambs are sacrificed on Nisan 14, before the Seder and thus before, not during, the traditional weeklong Feast of Passover.

Every Sabbath is preceded by a Day of Preparation, when meals are prepared, candles lit, and other chores performed that are unlawful on the Sabbath itself. Many arguments against a Friday crucifixion focus on misunderstandings of John 19:31 and its parallels:

Since it was the day of Preparation, and so that the bodies would not remain on the cross on the Sabbath (for that Sabbath was a high day), the Jews asked Pilate that their legs might be broken and that they might be taken away.

—John 19:31 ESV

The argument is that Friday was the first day of the Feast of Unleavened Bread, so it could not have been the previous day of preparation. It is true that the first and last days of the Feast of Unleavened Bread are important Sabbaths. But in Jewish custom, the regular weekly Sabbath that occurs during the Passover week is the most important of all the 7th-day Sabbaths.

So, in that particular year, there was a Feast Day Sabbath on Friday and a weekly Sabbath the following day, on Saturday. Confusion arises because many non-Jewish scholars believe, incorrectly, that it was unlawful to ever cook or make other preparations on any Sabbath. In fact, Jewish law makes an exception when two successive days are Sabbaths. Preparations for each are permissible on the preceding day, whether or not it, too, is a Sabbath.

Some confusion also arises due to a failure to recognize that the “First day of unleavened bread” is one day prior to the first day of the Feast by that name.

Then came the day of Unleavened Bread, on which the Passover lamb had to be sacrificed.

So Jesus sent Peter and John, saying, “Go and prepare the Passover for us, that we may eat it.”

—Luke 22:7–8 ESV

On Nisan 14, the day of the sacrifices, all hametz (leaven) must be removed or destroyed so that none at all is present during the entire week of the Feast.

Another verse that leads to confusion about the timing is John 18:28:

Then they led Jesus from the house of Caiaphas to the governor’s headquarters. It was early morning. They themselves did not enter the governor’s headquarters, so that they would not be defiled, but could eat the Passover.

—John 18:28 ESV

To most, this seems to imply that Jesus’ trial and crucifixion came on the day before the Seder, implying that the Last Supper was something entirely different. Not so—the Last Supper was a traditional Passover Seder. Any ritual defilement caused by entering Pilate’s presence would only last until sundown, so it would have no effect on eating the Seder meal. But it isn’t talking about the Seder. Instead, this refers to the chagigah (festival sacrifice) which was eaten with much celebration and joy in the afternoon following the Seder.

You may ask how the Wednesday crucifixion proponents manage to get “three days and three nights” out of a Wednesday to Sunday entombment. Mostly, there are two schools of thought. Some actually place the resurrection on Saturday and justify this by misinterpreting the passages about the women at the tomb. Others say that while Jesus was crucified on Wednesday, he was not placed in the tomb until evening, which would be early Thursday on the Jewish calendar. In that case, a resurrection early Sunday (on our Saturday evening) would meet the requirement.

A less prevalent theory is that the crucifixion was on Thursday. I believe that there are severe problems reconciling Sabbaths, preparation days, and calendar days if this approach is taken, but I will not cover it here.

Myth: By dying on Passover, Jesus became our Passover Lamb

I touched on this above. I suspect that the vast majority of Christian theologians would say that, at the very least, it is foundational that Jesus died on the same day as the Passover lamb or lambs, because He had to be seen as the fulfillment of the prophetic purposes of the Feast. If that were the case, then I ask why His throat wasn’t slit inside the Temple precincts and His blood splashed on the altar as required by Torah? How is it permissible that He died in a completely different manner, nailed to a Roman cross way over on the other side of the Tyropoeon Valley?

My contention is that Jesus did not die on the same day or the same time as “the Passover Lamb”, of which there were many thousands. In fact, I think that it was theologically necessary that Jesus did not die on the same day or in the same way as the Passover lamb! Had He done so, would He not have linked Himself prophetically to that sacrifice alone, to the exclusion of all others? The truth is that Jesus was the prophetic fulfillment of all of the sacrifices! And in terms of Soteriology, Passover is less important by far than, say, Yom Kippur!

Myth: As our Passover Lamb, Jesus brought salvation to the world

In a word, no! But didn’t Yochanan the Immerser—John the Baptizer—tell his followers to “Behold the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world” (John 1:29)? And what about Paul, who called Him “Christ, our Passover” (1 Cor. 5:7). Those are accurately reported sayings but mind the context! John was urging immersion as part of a ritual of repentance, connected, I’m sure, to the onset of the extended Days of Awe on that very day and extending to Yom Kippur, 40 days in the future. He was making no claim to offer salvation! Instead, he was pointing to the Messiah, often referred to in Scripture as “the Lamb of God”, or just “the Lamb.” Jesus didn’t die until some 3½ years later. And Paul was not talking about salvation at all, but rather separation of the Corinthian Church from the “leaven of sin.”

Yes, Jesus died on the cross to save us from our sins, but His sacrifice encompassed and surpassed all of the daily and seasonal sacrifices, not just the Passover lamb.

The Passover sacrifice was not even a sin offering! It was a type of fellowship offering. Sin offerings could not be consumed by the people, but they were required to eat their Passover sacrifice to symbolize their freedom from the bondage of sin and the resulting right to sup at God’s table, in fellowship with Him.

The Yom Kippur sacrifices were far more to the point of salvation, but even sin offerings only deal with incidental sin—not deliberate, malicious, God-defying sin. There was only one hope for that. Not a specific blood sacrifice, but simply the Grace of God, as symbolized at Yom Kippur by the Scapegoat, which wasn’t even killed! (Well, it was, but not as part of the ceremony; it was driven over a cliff in the wilderness so that it couldn’t come wandering back to town with the sins of the people.)

It was, then, as a goat—the Scapegoat—that “the Lamb of God” took away the sin of the world!

Myth: Peter accidentally cut off Malchus’ ear while taking a wild swing with his sword in an effort to protect Jesus

(Note: I have expanded on this subject in a separate post, Malchus’ Ear.)

The following quote from the Complete Jewish Bible, my personal favorite translation, sets the stage:

Then Shim‘on Kefa [Simon Peter], who had a sword, drew it and struck the slave of the cohen hagadol [high priest], cutting off his right ear; the slave’s name was Melekh [Malchus].

—John 18:10 CJB

First, it is unlikely that Peter was carrying a military sword that night after the Seder. Neither he, nor Malchus, was a soldier. Peter was a fisherman by trade and would be accustomed to carrying a knife for tending nets and lines, and for gutting fish. The Greek term here is machaira, which was probably a double-edged knife or dirk, a shorter version of a sword design that had been introduced into Israel by the Phoenician Sea Peoples. Nor do I think Peter was a trained fighter. We know he was impetuous, but was he an idiot? Did he think he could mow down a band of trained Roman soldiers and Temple guards? Was he distraught and attempting to commit “suicide by Roman soldier”? I think that if he had attempted a frontal assault in Jesus’ protection, he would have been reflexively cut to pieces before he drew a drop of blood, and quite likely the slaughter would have extended to the other apostles present, as well.

What I think really happened was that Peter took advantage of the soldiers’ preoccupation with Jesus, slipped around behind Malchus—his intended target—and deliberately sliced off his ear. Why Malchus? Because Malchus was the High Priest’s servant and right-hand man. The High Priest was probably not present, and Malchus was presiding. At any rate, harming the High Priest, had he been there, would have resulted in quick execution. By taking Malchus out, Peter would be insulting and effectively crippling the High Priest and, to some extent, the Sanhedrin. But then, why an ear, of all things? Because Peter wasn’t a killer, and taking an ear did the job! Priests, Levites and all other Temple officials were required to be more or less physically perfect. With a missing ear, he would be considered deformed and unfit for Temple service.

Yes, Peter was impulsive. But he was also smart.

For a complete series on the Principle Jewish Feasts, as specified in Leviticus 23, please see The Jewish Feasts–The Back of My Mind.