Posted on:

Modified on:

A topic that comes up over and over again on social media archaeology groups is the contention that the real Biblical Mount Sanai is the mountain Jabal al-Lawz in northwest Saudi Arabia.

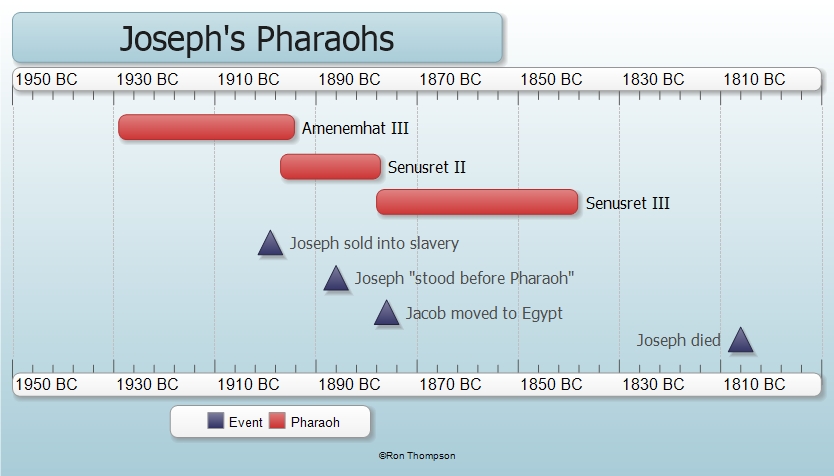

This is one of around a hundred astounding finds claimed by the late Ron Wyatt, who left his job as a medical technologist in Tennessee to chase his dreams as an amateur archaeologist. I don’t think that even a single one of his claims is valid. What he did was travel around the Middle East searching for things that superficially looked like something described in the Bible. A real archaeologist would produce tangible evidence for the find. Wyatt usually claimed to have found such evidence, but if so, only his own eyes ever saw it.

I previously disputed the contention by Wyatt’s many supporters that the traditional site of Mt. Horeb/Sinai, Jebel Musa, on the Sinai Peninsula, cannot be correct because that area was part of Egypt, not Arabia as Galatians 4:25 seems to require (see Moses, Paul, Sinai, Midian and Arabia). I thought I would spend a little time and space here discussing Jabal al-Lawz and Wyatt’s “split rock” themselves from a geological perspective. (Note: I have subsequently written The Saudi Sinai: More of the “Evidence”, in which I dispute some of Wyatt’s other claimed evidence on the subject.)

I should state at this point that it is difficult to disprove something that cannot be proved in the first place. My purpose here is to offer a more sensible explanation of two of the main talking points used to justify the Saudi Sinai claims—the black mountaintop and the split rock. I offer no proof of my own contentions. I’ve never been on that site, so all I can provide is sound principles and other folks’ photographs and research.

The “Burnt Mountain”

The most striking feature of the Saudi Mountain is the black summit, which is claimed, based on a superficial visual impression only, to have resulted from God’s appearance over the mountain:

16 On the morning of the third day, there was thunder, lightning and a thick cloud on the mountain. Then a shofar [ram’s horn] blast sounded so loudly that all the people in the camp trembled.

17 Moshe brought the people out of the camp to meet God; they stood near the base of the mountain.

18 Mount Sinai was enveloped in smoke, because ADONAI descended onto it in fire — its smoke went up like the smoke from a furnace, and the whole mountain shook violently.

19 As the sound of the shofar grew louder and louder, Moshe spoke; and God answered him with a voice.

—Exodus 19:16–19 CJB (emphasis added)

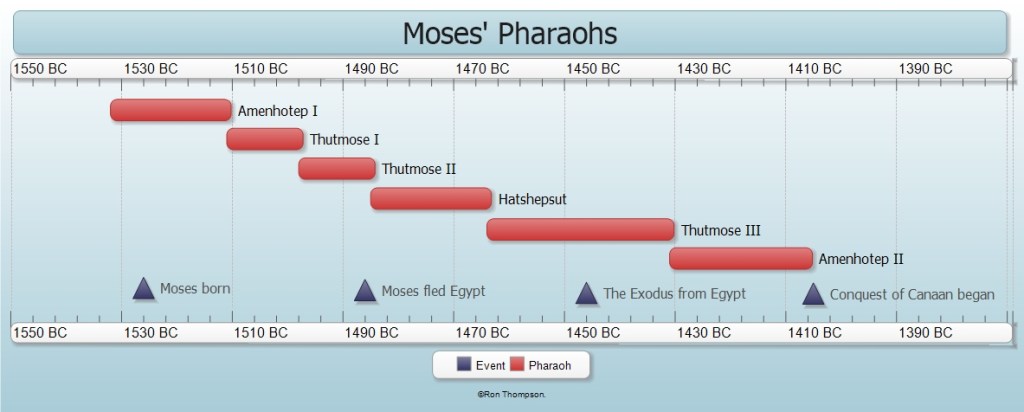

There is some confusion as to the proper name of the mountain in question. Ron Wyatt, Bob Cornuke and others Applied the name Jabal al-Lawz to the mountain pictured above, but al-Lawz is a somewhat higher peak to the north of that pictured, which is correctly called Jabal Maqla, meaning “Burnt Mountain”. That’s a minor point. The major question is, why is the peak blackened? Is that, as claimed by Wyatt and his followers, a remnant of scorching by God’s presence in the lightning, fire and smoke recorded in Exodus?

My interpretation of the passage above is that the lightning may have been literal, or perhaps static electricity, but that the fire and smoke were simply God’s sh’kinah glory, the same phenomena as the pillar of fire and smoke that led the Israelites for 40 years and that is never recorded to have damaged anything.

Furthermore, the contention that the mountainside was burned and that the burned area would still be visible after 3500 years, is beyond implausible. Compare the fire on Mt. Carmel when Elija confronted the priests of Ba’al some 600 years later; no trace of that remains, and Mt. Carmel is a known location.

Then the fire of the LORD fell and consumed the burnt offering and the wood and the stones and the dust, and licked up the water that was in the trench.

—1 Kings 18:38 ESV

I have not been to the site of al-Lawz, but I have seen many photos, and I have read formal geological descriptions of the area, which is strikingly similar to portions of the Rio Grande Rift Valley in New Mexico, which I am personally well acquainted with, having grown up in Albuquerque.

Geological origin

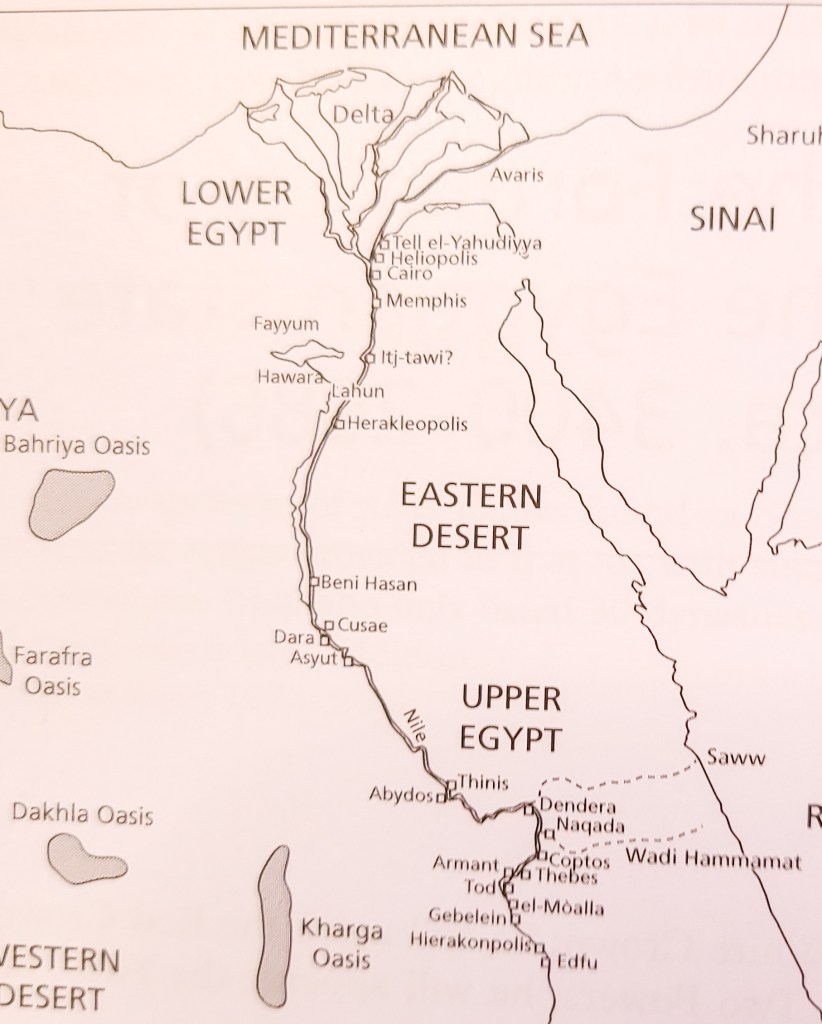

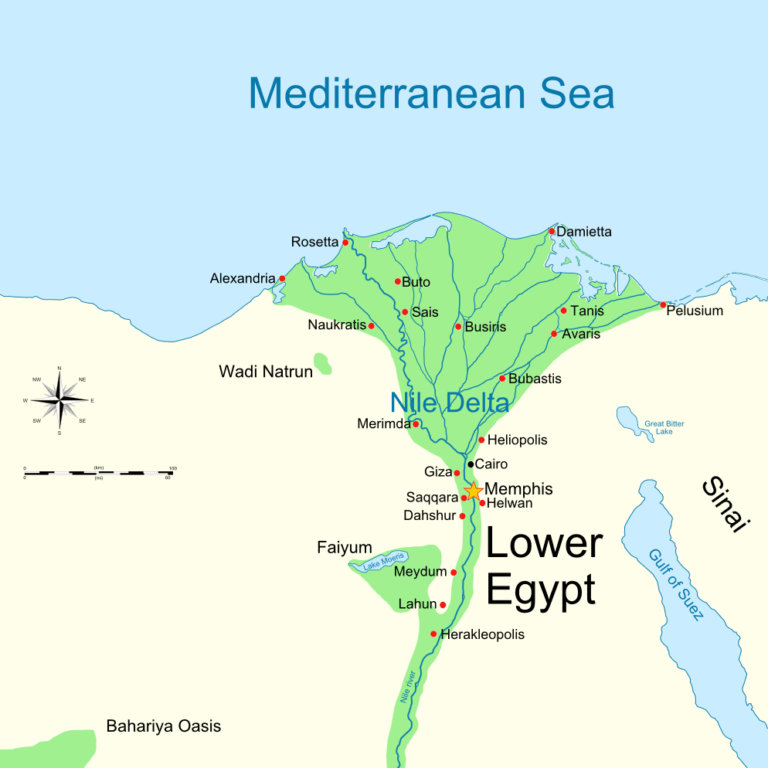

Biblical Midian lies within the northwestern extremity of the Arabian-Nubian Shield, which is a granitic batholith, shown in gray below, that spans the Red Sea. Granite magmas solidify deep within the earth’s crust and are exposed by succeeding uplift and erosion. The Red Sea itself is a more recent rift zone, where plate tectonics (continental drift) is pulling northeast Africa and southwest Asia apart. Rift zones are always associated with volcanic activity, and this case is not different, as is also shown on the map, fig. 3.

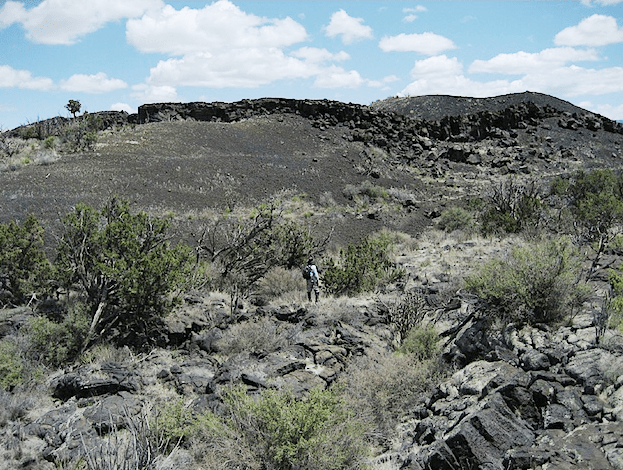

In reality, the blackened peak of Jabal Maqla is not due to scorching, but rather to lava flows, which are common along the rifting Red Sea and Jordan Valley. The geological literature describes the Jabal Maqla itself to be composed of a light-colored granite capped with volcanic rhyolite and andesite. The andesite is what makes the peak seem “burnt” (fig. 4). Rhyolite is a brown-colored lava which shows up on some aerial photos as volcanic dikes in older andesite flows.

The volcanic nature of the peak is particularly obvious from satellite imagery. The photos below (fig. 5 and the added fig. 5a) show the mountain and its surrounding drainage pattern. Note that the wadi on the north side is fed primarily from farther north, outside the blackened area. The tributary wadis that flow from the Jabal Maqla peak are paved with silt weathered from the darker andesite lavas.

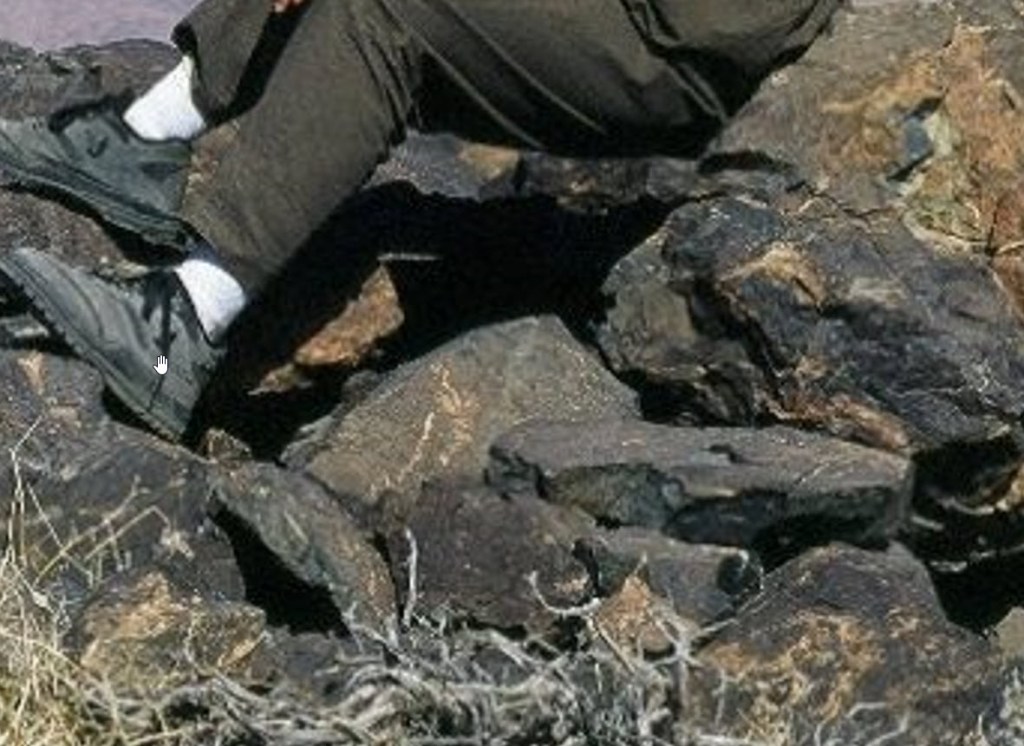

Next (fig. 6) is a view cropped from a visitor’s photo, shot on the summit of Jabal Maqla. The partially weathered rocks they are sitting on are clearly volcanic in origin. To my eye they are primarily black andesite, with lighter colored rhyolite inclusions.

A North American analog

For comparison, I am including as fig. 7 a photo of a typical New Mexico lava flow, from the region close to Carrizozo, south of my childhood home in Albuquerque.

The “Split Rock”

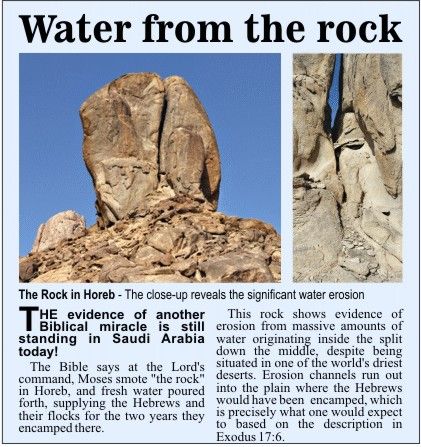

The second geological feature in the area that I want to discuss is the “split rock of Rephidim“, which Wyatt followers claim to have found to the northwest of Jabal al-Lawz.

1 All the congregation of the people of Israel moved on from the wilderness of Sin by stages, according to the commandment of the LORD, and camped at Rephidim, but there was no water for the people to drink.

2 Therefore the people quarreled with Moses and said, “Give us water to drink.” And Moses said to them, “Why do you quarrel with me? Why do you test the LORD?”

3 But the people thirsted there for water, and the people grumbled against Moses and said, “Why did you bring us up out of Egypt, to kill us and our children and our livestock with thirst?”

4 So Moses cried to the LORD, “What shall I do with this people? They are almost ready to stone me.”

5 And the LORD said to Moses, “Pass on before the people, taking with you some of the elders of Israel, and take in your hand the staff with which you struck the Nile, and go.

6 Behold, I will stand before you there on the rock at Horeb, and you shall strike the rock, and water shall come out of it, and the people will drink.” And Moses did so, in the sight of the elders of Israel.

7 And he called the name of the place Massah and Meribah, because of the quarreling of the people of Israel, and because they tested the LORD by saying, “Is the LORD among us or not?”

—Exodus 17:1–7 ESV

The claim is that this (fig. 8ff) is the rock that Moses struck with his rod, causing water to gush out to satisfy the thirst of the Israelites. As proof, they offer that the rock is close to Horeb; it is huge; it is split roughly in two, top to bottom; and it shows “obvious signs of water erosion.” Scripture says nothing about the appearance of the rock. Nearness to Horeb (Mt. Sinai) is only proof if Jabal al-Lawz really is Horeb.

I will discuss the question of erosion, below, but first I want to mention the probable origin of the rock and the rubble base on which it rests. This will have some bearing.

Glacial origin?

My initial reaction when I first saw photos of this granite behemoth and its associated elongated mound of rubble was surprise at what appeared to me to be glacial deposits in the Arabian desert! It would take a geological survey to establish the truth of my conjecture, but after research, I determined that there is indeed evidence of Mid-Cryogenian (Neoproterozoan) glaciation in the northern Arabian–Nubian (A-N) Shield region. This was a “snowball earth” period, one of two periods when virtually the entire planet was covered by continental ice sheets. The surface geology of the A-N Shield at this time is represented in gray on fig. 3, labeled as the Proterozoic basement complex.

Factors that led me to my conclusion were (a) the gigantic boulder that I thought surely must be a “glacial erratic“, an out-of-context rock too big to have been deposited by almost any other means; (b) the ridge on which it rests, appearing to possibly be “glacial till“, which is a deposit of rubble “usually described as massive (not layered), poorly sorted, and composed of multiple types of angular to sub-rounded rocks”; and (c) horizontal surfaces polished by fine grit and striated by larger fragments carried along at the base of the glacier.

Is the split miraculous?

Probably not. Such splitting is a normal characteristic of “frost wedging”, where moisture penetrates a small hole or crack in a rock, freezes, and wedges the opening larger. The ice melts, more water enters, and the cycle repeats. Over time, even huge boulders (and this one is said to be as large as 60 feet in diameter) will split. I have seen literally thousands of split rocks in New Mexico alone. The splits are almost always vertical, like this, because the water flows under gravity in the rock. I’ll provide two examples here:

Fig. 11 is a granite boulder, no doubt another glacial erratic, in the arid Joshua Tree National Park, in California. Fig. 12 is a photo of what is now a popular climbing spot near Albuquerque. Frost wedging accounts for probably all of the fracturing seen here. I did not take this picture, nor am I a rock climber, but some 50 years ago I stood either on that spot or on one very much like it close by, after hiking up along the axis of the ridge with a friend. Imagine my terror…

Erosion in and around the split rock

Descriptions of this rock always say there is “obvious water erosion” associated with it. Doubting Thomas Research Foundation (DTRF) is one organization that was apparently established by an individual to promote Jabal al-Lawz and its features. In one article they state about the split rock, “The erosion is within this split, along several paths descending from the base of the rock, and in the front and back of the hill at the bottom.” I will respond to this by commenting on photographic evidence I have seen.

Weathering of the megalith

Transportation of glacial till is slow and involves pushing, rather than rolling or tumbling. Rocks embedded in the till might become fragmented, or partially fractured, or chipped at the corners, but only roughly rounded. If sandwiched between ice and the underlying rock surface, polishing and scoring may result. I am assuming that the split rock is a glacial erratic that ended up at the top of the pile when the glacier melted. Sitting there, in that environment, it would have been subjected to three major weathering agents: frost wedging, exfoliation, and wind abrasion. The latter of these is mostly ineffective against hard igneous rocks.

However, both frost wedging and exfoliation are evident here. First, the frost wedging that I discussed above is undoubtedly responsible for the big split, and also for the oblong rock fragments littering the floor of the split, as well as the angular fissures in the walls of the split, as shown in fig. 13, below. I have also seen video footage of thin flakes of rock on the split’s floor. This was obvious debris from exfoliation—the eggshell layers that can be clearly seen in fig. 13.

Fig. 14 exhibits exfoliation on the external surfaces of the megalith, and on the rocks in the photo’s foreground. Exfoliation is due to heating and cooling of the rock itself, as opposed to thermal cycling of water in rock fractures. Temperature changes within the rock will be felt more quickly at the surface than under it, causing differential expansion and contraction. Since the granite is crystalline and brittle, an outer “skin” will eventually separate from its substrate. Such flakes, still clinging to the surface, can be seen in both photos, fig. 13 and fig. 14. Weathering by exfoliation typically rounds the surface of boulders. A great example of this is the Half Dome pluton, in Yosemite National Park.

A supporting structure?

DTRF (see above) also makes the following observation: “At the top of the hill, on one side of the split rock, is a large rectangular rock that may be holding the split rock upwards. In theory, this rectangular rock may serve a logistical (sic) purpose if the Exodus story is accurate. It would hold the split rock up for the scene to take place, as well as provide a safe spot for Moses to stand after striking the rock.“

Referring back to fig. 8, I assume that the author is referring to the vertical block immediately in front of the split rock, on the right or more probably the horizontal block on the left. From the photos I’ve seen, I would presume these to both be merely additional segments of the same boulder. Both are effectively separated from the main “lobes” of the boulder by wedging surfaces. To clarify, I have very roughly sketched what I see as the edges of major wedging planes in fig. 15.

A plinth for the split rock?

Of more interest to me, shown in fig. 16 (a crop of fig. 8), is the more or less flat surface that the megalith is sitting on. The regularity of the apparent cross-hatching on top of this rock surface suggests a striated and polished surface caused by dragging at the base of the glacier.

Erosion of the rock piled beneath the split rock

DTRF also noted erosional channels on “several paths descending from the base of the rock“. Other visitors to the site frequently mention such paths, or troughs, running from the split rock, down the face of the rubble, to the wadi below. The more astute acknowledge that this could be due to millennia of natural runoff. Others insist that there is not enough rain in the region to account for the erosion they see on the slope. Some visitors evidently account for the rubble-strewn mound itself by appealing to a strong flow of water from the rock after it was split by Moses’ rod.

I have seen one such erosional channel on video, but as a former desert-dweller, I have to say that it is not very impressive, and not visible on any of the photos presented here. Nor would I expect it to be. Clear, potable water simply does not erode solid granite blocks. Even if this rock had gushed water for the year that the Israelites stayed on Mt. Sinai, the only effect it would have on this mound would be to wash away small particles, from clay-sized through perhaps some cobbles. In the geologic ages since this mound was deposited, I would expect no more than the amount of erosion that is actually seen here.

DTRF seems to suggest that the rock might be limestone. if so, it might be dissolved by low pH water flow. It is not limestone. It is granite with other hard silicates mixed in, not carbonates.

Erosion in the surrounding wadi

DTRF on the wadi: “The ground level on both sides of the hill is smooth and uneven, giving the visual appearance of former water flows being there. It appears distinct from the rougher terrain that surrounds the site.” That is a good description of what can clearly be seen in photos and videos of the area.

He also states, primarily with respect to the rubble mound: “Yet, there is a lack of rainfall in this area of the world and there aren’t significant flash floods that could explain the apparent water erosion.” I totally disagree with this statement.

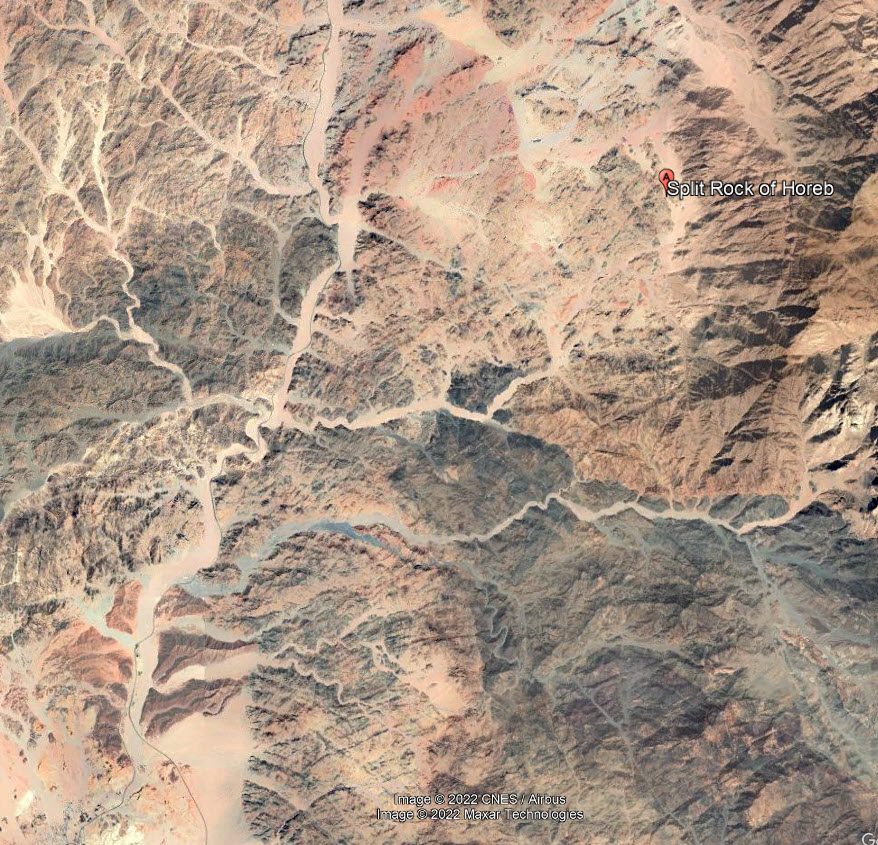

I suspect that this area (the Hijaz) of northwest Saudi Arabia gets no more than a few inches of rain in a year, but the complex dendritic drainage system visible on satellite images (see next three figures) shows that there is plenty of flash flooding to move loose sediments for long distances, over time. Fig. 18 shows that the split rock lies central to a catch basin collecting runoff from the mountains to the east and south. In other words, erosion around the rock is from drainage upstream of the rock, not from the rock itself.

Above the split rock, in the east, there is another terrace and a larger catch basin. Water from that terrace cascades downwards, downstream of the rock, as is seen more clearly in fig. 19, an oblique view from the west. Referring back to fig. 18, water from these two basins flows downstream to the northwest, to an intersection with a main-channel wadi that flows south-southwest and ultimately empties into the Red Sea.

Fig. 20 is a wider-angle 3D view, from the southwest. This is the best view to see the scope of erosion in the area, and reveals that the area east of fig. 18 is a broad, flat, plateau.

I decided to add fig. 21 to emphasize the elevation changes in the region. Jabal Maqla is not marked here but is near the top edge of the photo in the blackened region. If the Israelites were camped near their water source at the split rock, then none of the highland areas marked here, and especially not Jabal Maqla, were easily accessible.