Recall that in 1Kings 19, the Prophet Elijah has fled from the irate Queen Jezebel and is hiding in a cave near Mt. Horeb (Sinai). He is moaning about his fate, and God drops in to confront him:

And he [God] said, “Go out and stand on the mount before the LORD.” And behold, the LORD passed by, and a great and strong wind tore the mountains and broke in pieces the rocks before the LORD, but the LORD was not in the wind. And after the wind an earthquake, but the LORD was not in the earthquake. And after the earthquake a fire, but the LORD was not in the fire. And after the fire the sound of a low whisper.

—1 Kings 19:11–12 ESV

Two interpretive issues stand out here for me. The first is God’s demonstration for Elijah’s benefit of His power to control events, including even the forces of nature. That will be the subject of most of this post.

The second is an interesting side issue: how does God normally communicate with humans? Over the years I have heard many pastors and teachers refer to the inward prodding and conviction of the Holy Spirit as “God’s still, small voice.” That is a distortion of theology going back, I think, to the early church fathers. The ancient Jewish Rabbis taught that God most often spoke to His people in post-prophetic (intertestamental and following) times audibly but quietly, in a low, soothing whisper. This has been termed, in Aramaic, the bat kol, or “daughter voice”, and you can read one description of that here.

Some background before I proceed…

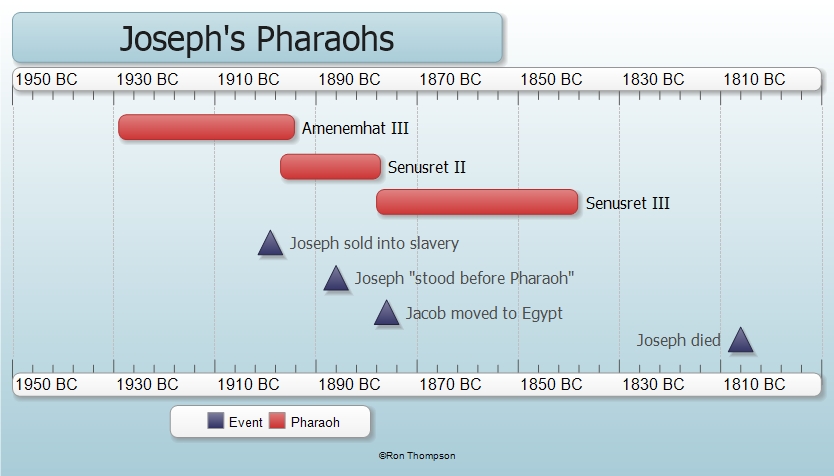

Some time back I read a book titled Between Migdol and the Sea: Crossing the Red Sea with Faith and Science, by Carl Drews. Drews is, like me, a self-taught amateur theologian with a technological background. He is also, again like me, passionately interested in the Egyptian sojourn, the Red Sea Crossing, the years of wandering, and the conquest of Canaan. The main difference between us is that I am a Conservative Evangelical who believes in the Divine inspiration and inerrancy of Scripture, while Drews takes a “Higher Critical” approach to Scripture.

The central reason for Drews’ book is to provide an engineering analysis of the following verse in order to discover the most likely site of the Red Sea (Sea of Suf) crossing:

Then Moses stretched out his hand over the sea, and the LORD drove the sea back by a strong east wind all night and made the sea dry land, and the waters were divided.

—Exodus 14:21 ESV

Drews is an expert on mathematical modeling, i.e., using computers to simulate real-world conditions. For example, meteorologists use mathematical models to provide fairly accurate weather forecasts and to predict storm movements. Astrophysicists use them to study how stars and galaxies form and interact. In my own field of petroleum engineering, I have used (and even designed) them to predict reservoir responses, such as oil and gas flow in rocks and pipelines, and depletion of reservoir pressure.

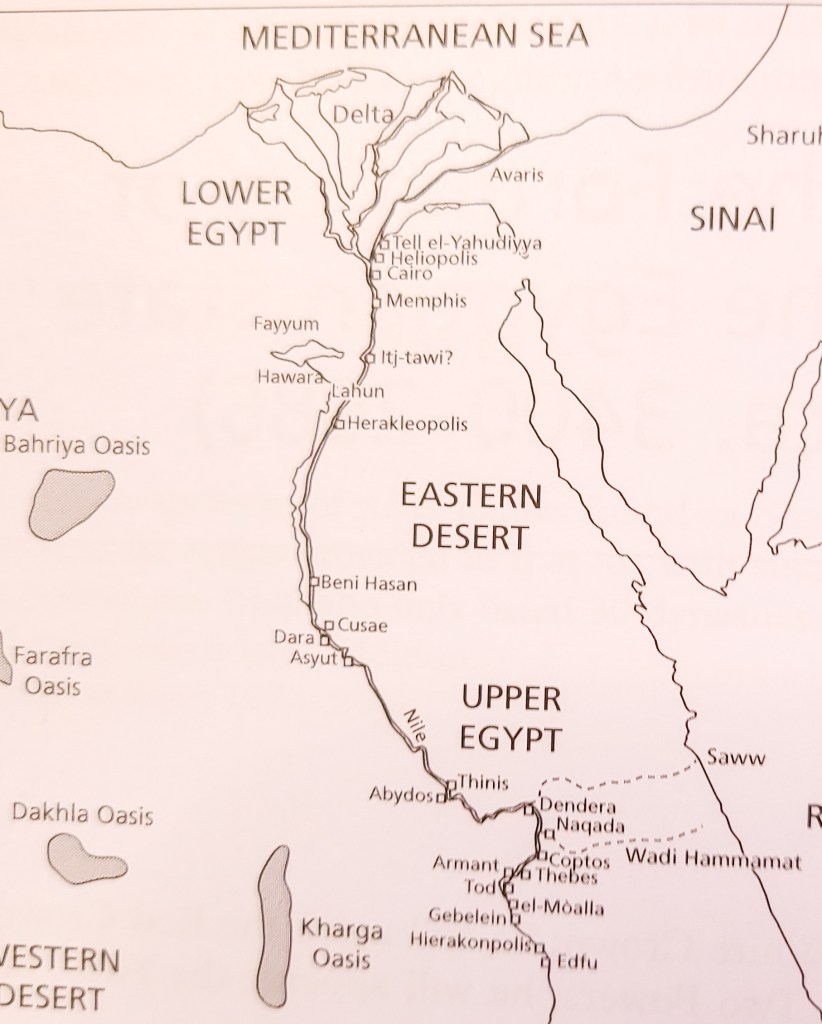

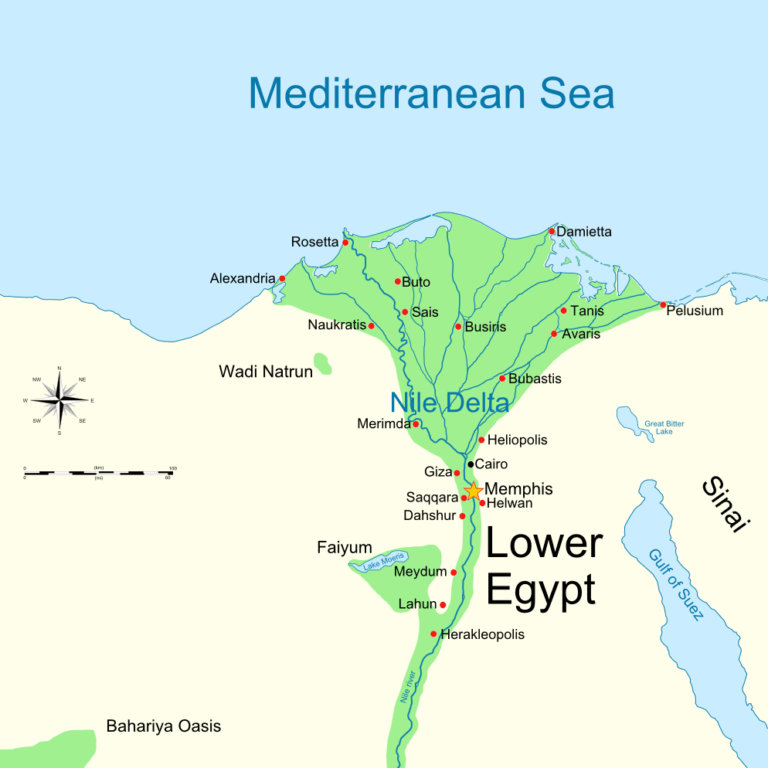

Drews used computer modeling to study “wind setdown” at various supposed locations of the Israelite crossing of the Red Sea. Setdown is a form of storm surge. Where high winds blow across an expanse of open water, shear forces can move the surface waters, piling them up on beaches and exposing shallow beds that are normally flooded. Drews proved, conclusively I think (but see below), that wind blowing across any body of water in the Egypt/Sinai/Arabia area, with one exception, would have to blow so hard to achieve the necessary setdown effect that no human could survive the crossing. Not the currently favored Bitter Lakes area on the present-day Suez Canal; not the current fad choices, at Nuweiba Beach in the Gulf of Aqaba or the Timor Straits area at the southwest extremity of Aqaba; and not the traditional (my own preferred) area in the northern Gulf of Suez, south of Suez City.

The one exception found by Drews is the shallow Lake of Tanis in the Nile Delta. He states that a strong easterly wind has been historically known to drive the water off the shallows from time to time, and that at those times the lake can be traversed by foot. His premise is that the Exodus miracle is in the timing, not in the actual moving of the water.

But consider that the crossing of the Red Sea, wherever that may have occurred, was the definitive, miraculous demonstration of God’s awesome power, whereby He showed His people, for all time to come, that He is worthy of all praise, glory and undying worship!

We know that God transcends time and place. He sees everything, everywhere and everywhen! So, Drews is asking us to see God checking His Weather Channel listing for the next hundred years or so, finding a convenient windstorm predicted for the time period, and deciding, “Yeah that would be a good time to send Moses to get my folks out of Dodge.”

I don’t buy it! What God came up with was something way, way more spectacular!

So, here’s where I’m going with this…

If you have heard many sermons on the Ten Plagues of Egypt, then you have probably heard that each plague was a challenge to one or more of Egypt’s pagan gods. In each case, the True God bested the pagan deity at his or her own specialty. Time and time again throughout Scripture, you see God delivering judgement, warnings or promises through or while accompanied by natural forces. This is partly a demonstration of His awesome power, and partly a polemic against the pagan deities that His people tended to fear or follow. Sometimes the accompaniment is a small thing, like a bush that burned without being consumed, or a gourd that withered and died in a hot wind. Sometimes much more, like fire and smoke over Mt. Sinai.

Read again the passage I quoted to start this post. Elijah was waiting to hear from God. When he felt a mighty wind, he thought it was the arrival of God. When he felt an earthquake, he thought, “Surely this is God…”. When he saw a fire, he probably remembered that it was right there on Mt. Sinai where God had appeared to the Israelites in fire and smoke. Surely God brought all of those things along to remind Elijah what He could do, but in this case, Elijah needed also to hear a tender voice.

God’s wind

I’m going to concentrate the rest of this discussion on the wind, because this is a particular idea that I have been exploring recently. Pagan wind deities tended to be particularly important in the ancient world because wind is almost always with us, and some of the most powerful natural phenomena are related to wind. In particular, this was true in Egypt, and therefore front and center in Israelite memory and lore. By the time of Moses, Egyptian mythology had merged the Sun God, Ra, with the God of Wind and Air, Amun, to produce the chief deity of that age, Amun-Ra.

Hebrew is a language that is rich in homonyms, or words with multiple meanings. The word רוּחַ, or ruach, is one of these. Depending on the context, ruach can mean “breath“, “spirit“, or “wind“. Sometimes there are specific clues in the context, like in Gen 1:2, where it appears as “the Spirit (Ruach) of God”, evidently referring to the Holy Spirit (Ruach ha-Kodesh). Very often, God’s miraculous works are accompanied by ruach. Bible translators have their reasons for choosing a particular meaning for a Hebrew term, but in some of those cases I have begun to wonder, “Is this interpretation cast in stone, or was it an assumption that has become ingrained as an unquestioned tradition?” Is it Spirit, is it literally wind, or is it perhaps both? I think that, perhaps, the idea of “both” has been underappreciated!

Take, for example, the following:

The festival of Shavu‘ot (Pentecost) arrived, and the believers all gathered together in one place.

Suddenly there came a sound from the sky like the roar of a violent wind, and it filled the whole house where they were sitting.

Then they saw what looked like tongues of fire, which separated and came to rest on each one of them.

—Acts 2:1–3 CJB (emphasis added)

Here we see a great spiritual miracle, the imparting of the indwelling Holy Spirit, accompanied by two physical phenomena: the sound of wind in the sky above them, probably indicating that wind was in fact blowing; and “tongues of fire” over the individual recipients.

What about “the strong east wind” that we observed in Ex 14:21? The verb in the phrase translated as “drove the sea back” (ESV, NIV, et al) or “caused the sea to go back” (CJB, KJV, et al) has the Hebrew root הָלַךְ (halakh, to walk, or go). It is described by Strong’s as having, “a great variety of applications, literal and figurative”. The specific form of the verb appearing here, וַיּ֣וֹלֶךְ, is syntactically a Hiphil, which I’m told makes the passage read more like “caused the sea to go [back]”. What is clear to me is that it was God who moved the waters. I don’t believe that you can say definitively from the Text whether the wind was His agency or was simply an accompanying phenomenon as seen elsewhere in Scripture. Since I am theologically convinced that the event required more than a minor “miracle of timing”, then I believe it is fair to say that Drews’ research proves scientifically that wind could not have been the agency. God miraculously parted the waters, while announcing His presence with a strong but less than lethal wind. For me, that’s a satisfying answer that makes any of the candidate crossing sites tenable!

Though he may flourish among his brothers, the east wind, the wind of the LORD, shall come, rising from the wilderness, and his fountain shall dry up; his spring shall be parched; it shall strip his treasury of every precious thing.

—Hosea 13:15 ESV

East Wind

Is there any significance to the easterly wind direction? Absolutely! The prevailing wind direction in the northern temperate regions is westerly. In the Eastern Mediterranean region around Anatolia, the Lavant and Egypt, these winds bring ashore relatively cool, moist sea air. But during certain seasons there is sometimes a dry, hot wind blowing out of the deserts to the east and southeast, raising temperatures and withering crops. This is the beruakh qadim (“east wind”), or sometimes for brevity, just the qadim (“easterlies”), of Scripture. A more modern term for these winds is the Hebrew, sharav, or in Arabic hamsin winds. If the rain is God’s blessing on the Land, then the east winds are surely His curse. It is easy to see why the east wind appears over and over in Scripture, especially in prophecy, to symbolize and accompany God’s judgement.

Conclusion

Many creationists believe that Earth’s present topology is mostly the result of upheavals caused by the Flood itself. At the time represented by Genesis 8:1 (after the flood itself, when things had calmed down), one would thus expect that the peak of Mt. Ararat was close to its current height of over 16,000 feet above sea level. Wind alone could not have dropped the water level over 3 miles! Only the power of God could have caused the flood, and only the power of God could have ended it! My conclusion is that either the wind was there as God’s signature, or ruach should have been translated as “Spirit” here, as it was in the similar scenario of Gen 1:2.

God remembered Noach, every living thing and all the livestock with him in the ark; so God caused a wind [ruach] to pass over the earth, and the water began to go down … It was after 150 days that the water went down.

—Genesis 8:1–3 CJB

I opened with Elijah in a cave, expecting God to appear to him in wind, an earthquake, or fire. I’ll close with a parallel text, with another prophet looking to the end times.

But the multitude of your foreign foes shall be like small dust, and the multitude of the ruthless like passing chaff. And in an instant, suddenly,

you will be visited by the LORD of hosts with thunder and with earthquake and great noise, with whirlwind and tempest, and the flame of a devouring fire.

And the multitude of all the nations that fight against Ariel [possibly meaning “altar hearth”, but referring here to Zion], all that fight against her and her stronghold and distress her, shall be like a dream, a vision of the night.

—Isaiah 29:5–7 ESV (emphasis added)