Yesterday I was watching the re-airing of a 2020 episode of Impossible Engineering on the Science Channel. The episode, titled Spy Plane Declassified, was about the reconfiguration of a Boeing E-3 Century airplane as an AWACS (Airborne Early Warning and Control System) aircraft.

Midway into the program, I was thrilled to see a segment featuring a man who, though I knew him for only a few months, was probably, after my father, the first man who significantly influenced the future course of my professional life.

During my mid to late teens, I took two summer jobs with Federal agencies. The first was on a Forest Service surveying crew, working on a road project on the fringes of the Navajo Reservation near Bluewater Lake, New Mexico. The second was a civilian job at the Air Force Special Weapons Center at Kirtland Air Force Base in Albuquerque. This job was in 1965 right after my graduation from high school.

At AFSWC, I reported directly to a young Air Force Captain, Carl Baum, now deceased, who was directing the Center’s research on EMP (Electromagnetic Pulse) defense strategies. EMP was then (at the height of the Cold War), and still should be, a grave national security concern. Strong pulses of high frequency electromagnetic energy such as those generated during air detonation of a nuclear bomb can disable and even destroy electronic equipment of all types within a huge radius. A few bombs detonated over America could potentially shut down our civilian infrastructure for decades, because even the facilities and equipment needed for repair and replacement would be crippled. But our focus at Kirtland was on finding means to improve the “radiation hardening” of military equipment against such an attack.

Of course I was a “gofer” in that facility, but Captain Baum and his staff all took an interest in me as a budding scientist. My principal duty was to run “IBM cards” and printouts back and forth between Carl’s desk, his programmers and keyboarders, and the Control Data CDC 6600 supercomputer down the hall.

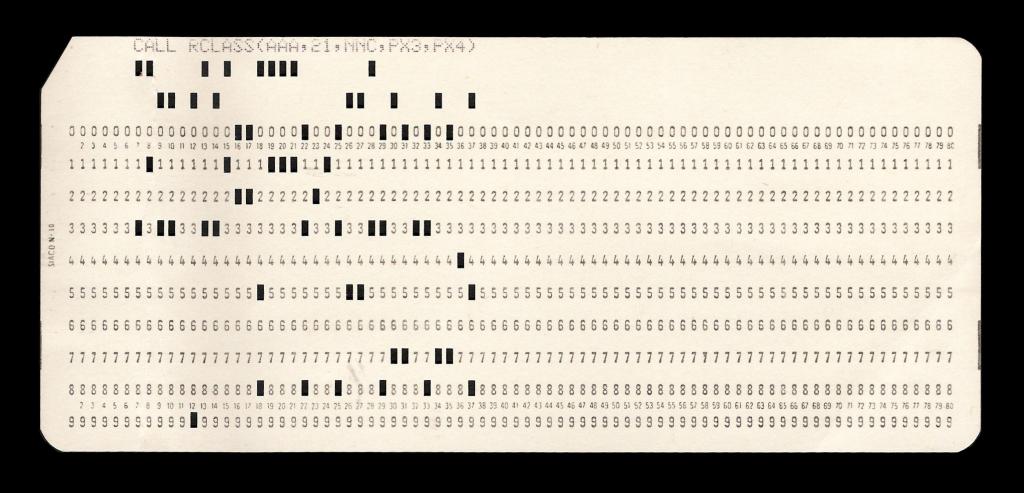

In practice, I was present for many conversations between the scientists. A simulation run or test results would come back, Carl would examine the data and graphs, and out of his genius brain would pop a new complex wave equation to model what changes might happen to the EMP field if we do such and such or change so and so. Off would go the programmer to plug the new equation into a new simulation, then I’d take it to the keypunch operators, prepare the program deck, and haul it off to the input desk.

But I still ended up with a lot of free time. Carl was at heart an academic. Over the years he did frequent guest lectures around the world, and he ended his career as a professor at the University of New Mexico. He asked me if I’d like to learn FORTRAN, the computer language of choice for research back then. Sure! So, he assigned a Staff Seargent to teach me, and in just a couple months I became proficient enough at it that two years later I was able to land a job at the University of Texas Computation Center as a consultant tasked with helping professors and students debug and improve their faulty FORTRAN programs.

I never saw Carl again after that summer, but I never forgot him, or heard of him again until now. As a kid, I always loved astronomy and physics, but for reasons beyond the scope of this post, I had decided to pursue a career in marine biology, instead. Because of Carl’s influence and the computer training he gave me (long before the days of personal computers), my interests swerved back onto their original path. My father insisted that I start with general studies at a small college for two years. I ended up as the only physics major at Eastern New Mexico University, and from there went on to double major in math and physics at Texas.

Full tribute online, by Frank Sabath, W.D. Prather and D.V. Giri.