Posted on:

Last modified on:

- Before I begin…

- Moving on…

- Hermeneutics and the Golden Rule of Biblical Interpretation

- Limitations of Science

- Proving the Bible

- Moses was a prophet!

- Previous posts in this series on the topic of creation

- Revisiting Genesis 1

- Prologue: Gen 1:1–5

- The overwhelming problem with Light on Day 1:

- Interpreting verses 1:3–2:3

- A better idea

- Bibliography

Before I begin…

Before getting into this, I’ve been asked why I keep alienating my friends by harping on a version of Creationism that most of them consider to be unbiblical. I can respond to that in several ways:

- First, I’m not really “harping” on it at all. This is a multipart series that I’ve planned for quite a while, to replace something I did years ago. I’ve still got two or three chapters to write before I’m finished with it. I did the same thing with my series on The Jewish Feasts.

- I’ve been vitally interested in both theology and astrophysics since, literally, my pre-teen years. I write about what interests me most.

- I don’t consider that one’s interpretation of Genesis 1 is a “fundamental of the faith“, but many of my friends do, and I am convinced that the currently mandatory “Genesis Flood Theory” is an unnecessary stumbling block for many lost souls.

- Although many wonderful Christians would refuse to fellowship with me because I’m not a Young Earth Creationist, I don’t feel the same about them; but I suppose I’d like to convince them that I’m “righter than they are.”

As stated below, “With respect to the question of Creation, the central, foundational Truth of all Scripture is that the One, True, Eternal, Triune God, by His own power, created and sustains all else that exists in the cosmos.“

Moving on…

My views are driven by several axioms:

- God is both omnipotent and sovereign, so He can do whatever He wants to do, however He wants to do it!

- The Bible, as originally written, is the inerrant, irrevocable, Word of God.

- The Bible we now possess (at least insofar as the accepted canonical books are concerned) is substantially the same holy Word as the originals, but subject to a very limited extent to human error in translation and interpretation.

- Correct interpretation (exegesis) of Scripture requires a consistent hermeneutic, which among other factors, includes recognition that some scripture is not meant to be taken literally, as discussed in the next section in relation to The Golden Rule of Biblical Interpretation.

- A consistent hermeneutic also must require recognition of the cultural background of both the writer and the ancient reader.

- Though Holy Scripture is as valid and vital today as it ever was, correct interpretation demands unequivocally that modern culture and tradition not be anachronistically imposed on the writers and readers of the day in which they were written.

- Because God is not a liar or an author of confusion, we must recognize that the testimony of God’s Word cannot conflict with the testimony of His Created World when both are rightly understood.

Hermeneutics and the Golden Rule of Biblical Interpretation

“When the plain sense of Scripture makes common sense, seek no other sense; therefore, take every word at its primary, ordinary, usual, literal meaning unless the facts of the immediate context, studied in the light of related passages and axiomatic and fundamental truths, indicate clearly otherwise.”–Dr. David L. Cooper (1886-1965),

founder of The Biblical Research Society

The above quote is known by many expositors as “The Golden Rule of Biblical Interpretation.” I read somewhere that this has often been shortened to “When the plain sense of Scripture makes common sense, seek no other sense, lest it result in nonsense.”

Implicit in the above is the assumption that the “plain sense of Scripture” sometimes does not seem to make sense. Certainly, when that is the case, you must first question your own common sense, but that doesn’t always solve the problem.

Few conservative Bible scholars believe that every word of Scripture is meant to be understood literally.

That is troubling to many, because the alternative opens the door to subjectivism and arbitrary conclusions. Yet almost all the great conservative Bible commentators practice a hermeneutic (a set of formal principles for Biblical interpretation) that allow for non-literal text, including parables, figures of speech, anthropomorphism, poetic exaggeration, and a host of other confusing factors. Not to mention translational difficulties.

None of that subtracts from the central truth that “all Scripture is God-breathed.” It is axiomatic to me that the Bible is inerrant in its original language and the original manuscripts. Yet some folks read my opinions, especially respecting emotional themes like creation, and make snide comments like, “So you believe it’s inerrant except when it isn’t!”

So, to clarify, I don’t think there are any substantive problems with corruption of our Scriptures over the millennia. There are, however, problems with translation, but few of those are impossible to unravel, with sufficient attention to the linguistic and cultural background of the inspired humans who penned the words, and those to whom the words were written.

There are also “mysteries.” Most Evangelicals are happy to admit that Paul revealed things hidden within Scripture that were mysteries with respect to the New Testament Church. The Church itself being one of the chief mysteries! The dual advents of Messiah are another mystery now revealed. Yet many seem unwilling to consider that some things are still mysterious.

What I consider to be the biggest factor of all that contributes to doctrinal confusion and infighting in the Church is that some misinterpretations are imbedded into a nearly impenetrable wall of tradition.

Unfortunately, the reason there are so many Christian denominations in the world, and the reason they often have so much trouble getting along, is that each has its own particular list of what constitutes “axiomatic and fundamental truths.” For example, I was brought up in a “fundamentalist” sub-denomination of Baptists that teaches there is no such thing as a universal Church of all believers; only local churches are Biblical. To them this is an axiomatic and non-negotiable Truth, based in part on the simple fact that the Greek word translated “church” is ecclesia, which literally means “assembly.” After all, how can people scattered across the world and across many ages possibly assemble together?

With respect to the question of Creation, the central, foundational Truth of all Scripture is that the One, True, Eternal, Triune God, by His own power, created and sustains all else that exists in the cosmos.

That fact is stated clearly and concisely in just one verse: Genesis 1:1.

As for what that process looked like and how we should interpret Genesis 1:2–2:3, I regard that as still a mystery.

A 6,000-year-old universe and the Genesis Flood Theory of today’s Young Earth Creationists does not meet the commonsense test, not because God can’t do whatever He wants, but because the clear evidence of centuries of careful observation and analysis by very smart and dedicated professionals, both Christians and otherwise, can’t be ignored. God is not the Author of Confusion. He doesn’t plant lies in front of our face to test our faith.

Moreover, the universe is demonstrably dynamic, changing over time even as we observe. That isn’t “evolution”, it’s simply the application of forces and interactions decreed by God. We understand the physics of supernovae (the implosion of giant stars) and we observe them happening. We understand the process of star formation, and we see examples of every stage of that process. We can’t see the movement of stars and galaxies, but we can measure their movements using Doppler shift, similar to the clocking of a speeding car.

Limitations of Science

When I was young, scientific method was viewed as a simple, 3-step process:

- State a hypothesis.

- Form a tentative theory.

- “Prove” the theory, which then becomes a law.

But so many of the “laws” found under that paradigm have been subsequently found to be limited in scope (for example, Newton’s laws of motion are now known to be invalid for very large and very small masses), that the paradigm has changed:

Now, hypotheses still become tentative theories, but once a theory has become so well proved that it is accepted as true by most authorities on the subject, it still doesn’t get promoted to “law”. That is why it is utterly meaningless to say that “The Big Bang Theory” is just a theory!

Scientists now look for certain characteristics of a theory to judge how “well established” it is:

- Obviously, the more evidence supports a theory, and the less that appears to contradict it, the stronger it becomes. This evidence may be experimental, or it may be observational. If it is statistical in nature, then the results must be well within a recognized margin of error.

- To be considered a truly “scientific“, a theory must be judged to be “falsifiable.” That means that for all practical purposes, if there is no conceivable way that a theory can ever be proven false, then it must remain speculative in the minds of those who are not predisposed to take it on faith. This principle is the tool of choice for those who wish to exclude all discussion of religion, or “Intelligent Design“, as an alternative explanation.

- For a theory to become intrenched as factual, it is also necessary for it to successfully produce demonstrably true predictions, by means either of observation, logical arguments, or mathematics.

- The strongest theories are those that can be expressed by mathematics, because mathematics is the only truly “exact science“. Two plus two always equals four in our base 10 number system. The circumference of a circle divided by its diameter always equals pi (3.1415926…) in a Euclidean frame of reference.

Proving the Bible

Something I see online over and over again online is well-meaning Christians exclaiming over interesting archaeological finds that, “They prove that the Bible is correct.” No, they don’t! Science will never prove Scripture, and that is by God’s design, because He wants us to live by faith, not by sight. The most that science can do for us is to confirm the faith that God has already supplied to us.

At the same time, if we are worried that science will contradict our faith, then our faith is weak to begin with!

God has written of Himself in both Scripture and creation. The purpose of science is to help us understand creation. Embrace it!

Moses was a prophet!

According to Scripture, Moses was the greatest prophet of all times, other than Jesus. He didn’t personally see any of the events of Genesis, so how did he know what to write? Both the Old and New Testament contain numerous references to non-canonical source writings. Moses himself references The Book of the Wars of the Lord (no longer extant) in Numbers 21:14, which recorded some contemporary events, but I know of no sources that he could have used for events prior to the invention of writing. He could have gotten his information only from God. After-the-fact prophecy, so to speak.

How was that information communicated to him? Perhaps verbally, because we know that he and God talked to each other directly. Having nothing concrete to go by, I personally assume that from Genesis 11:10 forward, Moses’ inspiration was primarily verbal.

Verses 10–32 of chapter 11 constitute one of eleven so-called toledoth in Genesis. These primarily genealogical blocks of Scripture were included by Moses and are believed to be intended as section dividers.

Because the first 11+ chapters of Genesis consist of abbreviated, flowery accounts of earthshaking historical events, I see them as poetic discourse, a different genre from what follows. For that reason, I suspect that these chapters were conveyed, at least in part, via visions or dreams. There is a theological label for prophetic visions of past events: Preterism. A “full preterist” believes that all prophecy describes the past, in effect dismissing the possibility that prophets could foretell the future. I am far, far from that position! I am a “partial preterist” in that I refuse to dismiss the possibility that God can also reveal the unseen past to his prophets.

Typically, prophets preached and reported the content of visions and dreams, but not necessarily their interpretations.

Previous posts in this series on the topic of creation

In The Hijacking of Creationism, I laid out several of the views that Evangelical scholars have historically held in order to account for the apparent ancient age (13.8 billion years) of the universe. In particular, I focused on The Genesis Flood Theory, and its popularizer, Henry M. Morris. Today, 1/10/2024, I expanded on my bio of Dr. Morris. Yes, I am a little bit brutal with him, but his writings were frequently brutal towards those who disagreed with him.

In Does Science Trump Theology? I explore the intellectual domains covered by the two disciplines, similarities in the two, and how they should work together in Bible interpretation.

In Fountains of the Deep I draw on my own geological engineering background to present what I believe to be the most likely mechanism of the Genesis Flood. This mechanism is unlikely to have caused the distortion of the earth’s surface that followers of Morris demand. Incidentally, the 13.8-billion-year age of the universe is as firmly rooted in astrophysics and cosmology as the 4.54-billion-year age of earth is in geology. One of these days I’d like to hear a Young Earth Creationist explain how the Genesis Flood accounts for the cosmologic appearance of age.

In Geology a Flood Cannot Explain I randomly describe, from my own professional knowledge, a number of well-known geological features on earth that absolutely could not have been affected by a flood of any magnitude.

Fluid Mechanics courses for civil engineers are mostly irrelevant to understanding of the Genesis Flood, because they focus primarily on hydrostatics (forces exerted by water pressure on fixed structures like dams and canal locks), and laminar flow in engineered open channels and pipes. To the extent that they cover turbulent flow in natural channels like riverbeds, the primary interest is erosion of friable soils, sands and gravels. Before erosion can occur in solid rock, weathering must first break the rock down into smaller pieces, which is a process which usually takes years, if not centuries or longer. [I explore this fact in a post, Geology and the Saudi Sinai, part of a series on false evidence for believing that “the real Mt. Sinai” is in Saudi Arabia.]

Revisiting Genesis 1

I would like to take another look at the first few verses of Genesis 1 to present some ideas that you may not have considered before.

Prologue: Gen 1:1–5

Below, I present three very legitimate translations. The first is from an Evangelical favorite, the English Standard Version (ESV). The second is from the Jewish Publication Society (JPS). The third is from a new work, The Hebrew Bible, translated by Robert Alter over a 30-year period. Alter is a modernist, and not someone I would look to for dogma or Christian commentary, but from reading his books, I am convinced that he is, to his core, a top authority on Biblical Hebrew and Ancient Near Eastern literature. I don’t believe that his translations are colored by any sectarian presuppositions, and that makes him my top comparator while trying to separate what the Hebrew Bible says from what tradition claims that it says.

1 In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth. 2 The earth was without form and void, and darkness was over the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God was hovering over the face of the waters.

3 And God said, “Let there be light,” and there was light. 4 And God saw that the light was good. And God separated the light from the darkness. 5 God called the light Day, and the darkness he called Night. And there was evening and there was morning, the first day.

— Genesis 1:1-5 (ESV)

1 When God began to create heaven and earth— 2 the earth being unformed and void, with darkness over the surface of the deep and a wind from God sweeping over the water— 3 God said, “Let there be light”; and there was light. 4 God saw that the light was good, and God separated the light from the darkness. 5 God called the light Day, and the darkness He called Night. And there was evening and there was morning, a first day.

— Genesis 1:1-5 (JPS)

1 When God began to create heaven and earth,

2 and the earth then was welter and waste and darkness over the deep and

God’s breath hovering over the waters, 3 God said, “Let there be light.” And

there was light. 4 And God saw the light, that it was good, and God divided

the light from the darkness. 5 And God called the light Day, and the darkness

He Called Night. And it was evening and it was morning, first day.

— Genesis 1:1-5 (Alter)

Before considering the difficulties posed by creation of light on “Day 1” (verses 3–5), we first need to consider verses 1 and 2.

Verse 1: I think that the ESV Study Bible, with a couple amendments, states the interpretive problem in verse 1 fairly well:

[Verse 1] can be taken as a summary, introducing the whole passage; or it can be read as the first event, the origin of the heavens and the earth (sometime [on or] before the first day), including the creation of matter[, energy], space, and time. This second view (the origin of the heavens and the earth) is confirmed by the NT writers’ affirmation that creation was from nothing (Heb. 11:3; Rev. 4:11).

…

Heavens and the earth here means “everything.” This means, then, that “In the beginning” refers to the beginning of everything. The text indicates that God created everything in the universe, which thus affirms that he did in fact create it ex nihilo (Latin “out of nothing”). The effect of the opening words of the Bible is to establish that God, in his inscrutable wisdom, sovereign power, and majesty, is the Creator of all things that exist.

— Dennis, Lane T. and Wayne Grudem, eds., The ESV Study Bible. Accordance electronic edition, version 2.0. Wheaton: Crossway Bibles, 2008 (emphasis added, my additions are in brackets).

Probably half of the sources I use assume that verse 1 is a summary for what follows, ignoring the fact that none of what follows explicitly mentions the origins of the earth as a rocky planet covered by water. This view necessarily assumes that God created the individual building blocks (sub-atomic particles, atoms and molecules, and the forces that bind them) concurrently with forming them into the finished product. This is not outrageous but leads to a crucial contradiction which I will discuss below—namely that light is produced by matter, and is a manifestation of electromagnetism, which is an essential binding force.

The other half of my sources take the “first event” approach. Most of those place verse 1 on day 1. If you take it prior to day 1, then you more or less put yourself potentially in the “Gap Theory” camp, which I have occupied, but which is anathema to Young Earth Creationists because it can imply death before The Fall. I’ll save my comments on that objection for another post in this series. Unfortunately, this view is subject to the same contradiction regarding electromagnetic binding.

The ESVSB contention that “[the] Heavens and the earth … means ‘everything’” assumes that the wording of the Scripture is a merism, a figure of speech that encompasses the first element, the last element, and everything in between. This assumption is not provable, but rather can only be taken on faith—which I do. It is a figure of speech used frequently in the Bible.

The term “the heavens” is hashamayim in Hebrew. It is a plural form and is usually rendered as such in translations. Up to seven heavens were recognized in ancient literature, but most scholars today differentiate between just three heavens:

- The atmosphere around and above us.

- The cosmos beyond earth’s atmosphere.

- The heavenly realm inhabited by God and his host.

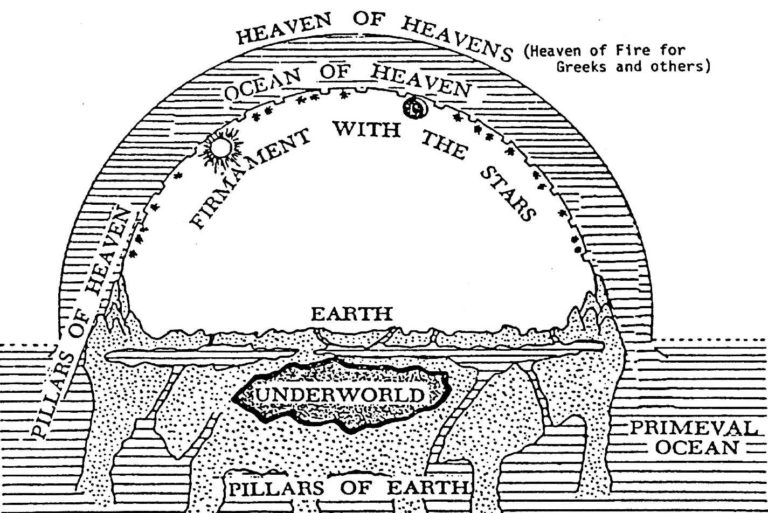

I would rather prefer a more general statement that the term “heavens” means everything above the surface of earth: As explained below, Moses and his readers would have envisioned several elements:

- The sky of air and birds.

- A solid dome (the “firmament“) from which hang the suspended sun, moon and stars.

- An ocean above, connected at the edges to the ocean below, and held up by the dome, (KJV, “firmament”).

- The home of God and His Divine Host.

The first event view is supported in particular by the JPS and Alter translations above (“began to create”), which place verse 1 at the beginning of what might be interpreted as a string of creation events, those described in the remainder of the chapter, and anything subsequent.

Verse 2: In verse 2, there are actually four separate interpretive issues, which I will gloss over here:

- “Without form (or formless) and void” and other translations, such as Alter’s “welter and waste.” The Hebrew, tohu wabohu, is linguistically of limited use to our understanding, because its usage in literary history is insufficient to allow a definite interpretation. Guesses range from “total chaos” to “undeveloped and unpopulated.” Halter deliberately chose his alliterative nouns to emulate the poetic language of the Hebrew rather than to take a position on precise meaning. Whatever the meaning here, I have generally pictured the state of the planet as an earth totally covered by water and shrouded in mist, which works very well with a Gap Theory and a flooded earth. However, I’ll mention another (better?) view below.

- “Darkness.” The Hebrew choshek can mean things like darkness (perhaps because light is absent), or obscurity because light has been masked or reflected away. Again, obscurity works best with Gap Theories, but see below.

- “The Deep.” The Hebrew tehom means either the deep sea, or the deep source waters of terrestrial springs which were viewed as interconnected with each other and with the sea (see Fountains of the Deep, where I discuss this in some detail).

- “The Spirit of God“, “a wind from God”, or “God’s breath.” The Hebrew ruach, can mean any of these things, and probably means all of them here. See God with the Wind for an in-depth discussion.

The overwhelming problem with Light on Day 1:

The definition of light

Just what is “light”, anyway? If you think of it as simply, “the absence of dark”, then you are way off base—it’s the other way around. As a noun, “dark” denotes a concept (the absence of light), rather than a tangible thing. “Light” is something very real and specific. I suspect that all of my readers have had enough education to realize that light is electromagnetic energy. All of you will no doubt have seen some version of a spectrum diagram:

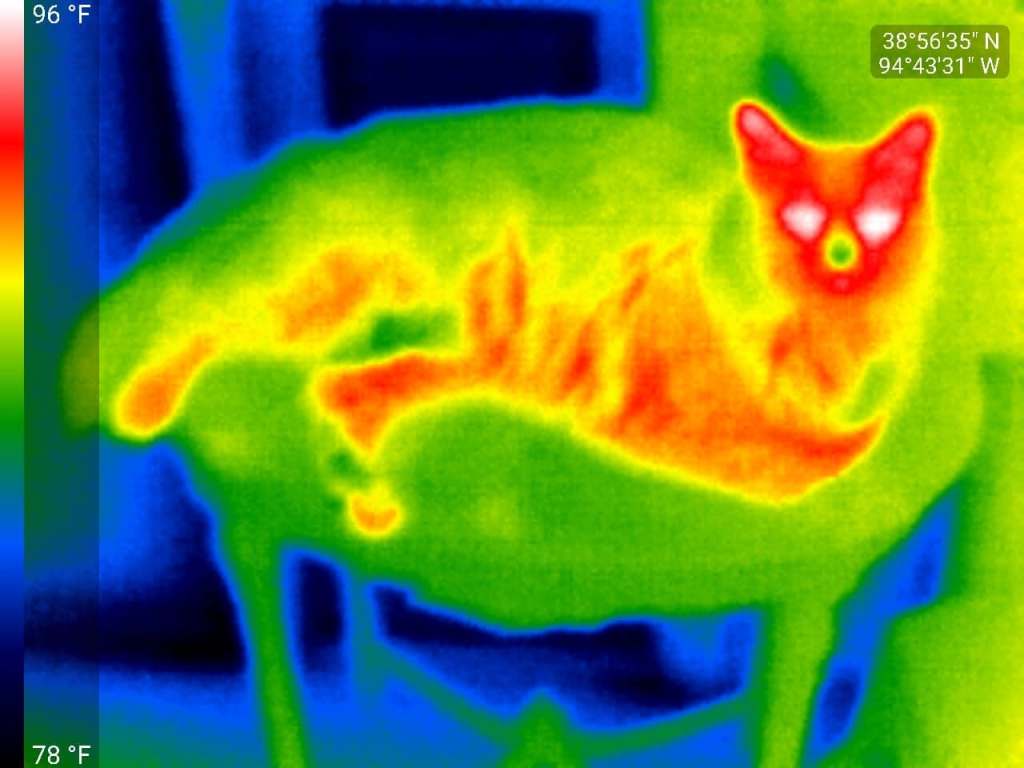

The problem is that most folks have a tendency to think of visible light as something that is fundamentally different from the rest of the spectrum, because our vision only detects wavelengths in a narrow band between about 400 and 700 nanometers. But the wavelength of electromagnetic energy is really an expression of how energetic the wave is. X-rays and gamma rays are fundamentally the same thing as visible light, just more energetic. Radio waves, radar, and microwaves are fundamentally the same thing as visible light, just less energetic. All of these things are emitted by matter, travel at roughly 186,000 mps as waves, and are detected in the form of massless particles called photons.

So, if God literally created light on a literal Day 1, did He create just visible light, or the entire spectrum? If He just created visible light, then I have to ask, “visible to whom?” Humans all differ slightly in their light sensitivity. Bats, most amphibians, and many fish and insects see well into the infrared. Many species of insects, fish, and even mammals (including dogs and cats) can see into the ultraviolet. Using instrumentation, humans can now “see” all wavelengths of electromagnetism.

And what do we even count as visible to a normal human? Sunlight reaching Earth’s surface on a sunny day is around 52 to 55 percent infrared, 42 to 43 percent visible light, and 3 to 5 percent ultraviolet. A biologist might say that “visible” means detectable using only our eyes, but we also detect longer and shorter wavelengths with other organs.

On the long-wave side of the spectrum, infrared (“below red”) is felt as heat on our skin; microwaves can penetrate skin, and if powerful enough, could even boil the water in blood and cells near the surface; and even longer UHF and VHF radio waves have been documented to set up resonant vibrations in structures like teeth with metallic fillings.

On the short-wave side of the spectrum, ultraviolet (“above violet”), which can cause sunburn and later melanoma; x-rays penetrate completely through our bodies and can cause damage to inner organs over time or can cause or kill cancers; unshielded gamma rays can cause catastrophic damage to human bodies.

Contrary to the diagram above, cosmic rays are not primarily light or even electromagnetic energy in any sense, but rather are characterized by alpha and beta particles (helium nuclei and protons) traveling at close to the speed of light, and thus possessing some of the same quantum properties as light.

The source of light

Light that reaches us from the sun is largely in the range of visible and near-visible light, but it starts out in the sun’s reactive core as gamma rays, high energy (short wavelength) byproducts of nuclear fusion. These gamma rays begin a “random walk” out of the sun’s core and through its conduction zone, repeatedly colliding with particles in the dense surrounding soup of hydrogen and helium ions, changing directions randomly, over and over again, and gradually losing energy (thus shifting to more benign longer wavelengths). Eventually, after something like 100,000 to a million years, they reach the sun’s surface and fly off in all directions at the speed of light, 186,282 miles per second.

An even more important consideration (mentioned above) is that, in the universe God created, electromagnetic energy (let me just call it “light” here, for brevity) is always associated with matter. There are a number of ways that light can be generated, but it always begins with matter. I’ll mention a possible exception below, under the heading “sh’kinah“, but for now, I’m talking about the light that all of us experience.

It is worth mentioning that all light is invisible until it strikes a detector. If you are in an empty, dark place and someone shines a flashlight past you, you may see the glowing source, but you will not see any trace of the beam, which consists only of a jiggling electromagnetic field, unless it strikes an air or dust molecule and reflects into your eye.

Most light in the universe is generated by stars like our sun, but all matter generates light, usually much less energetic than stellar gamma rays but still light, even if it is well below our range of sight. The human retina is populated by several types of light receptor: “cones” for detecting color when the light intensity is strong enough, and “rods” for detecting black and white in low light situations. My cat, Anna, can see me very well in a darkened (but not totally dark) room, because her retinas are mostly populated by “rods”.

Matter that is not heated to a glow, still generates heat, and that heat energy is radiated as light in the infrared region. If raised to a high enough temperature, the energy of the radiated light will eventually climb into the visible region, first red, and when hot enough, all the way to the blue side of the spectrum.

[Note: This is why the red and blue markings on faucets and automobile heater controls are so confusing and counterintuitive to me. To any scientist and most engineers, it should be red for cold and blue for hot, in spectral order.]

I took the photo of Anna, below, using an infrared sensor. The color isn’t real. The sensor’s pixels map the wavelengths of the infrared light in the scene and use an algorithm to determine the temperature that the pixel is “seeing”. False color is then added to encode it, as per the scale on the left. The warmest parts of the photo are her eyes, about 96°F. Next warmest is her face, followed by her tummy and legs. Her cold nose and the thick fur on her back and tail matches the cooler temperatures of the table she’s lounging on and the room to the right. The blue areas, our front door and glazed side panels, are quite cold. It was winter, and the windows here are single-glazed and very poor insulators.

In this photo, the small amount of heat registered from the window is a combination of heat from Anna and the room itself, being reflected back towards my sensor, heat generated by the window glass itself, and heat from outside conducted (see below) through the glass and woodwork.

All matter generates heat provided that its temperature is above absolute zero (−459.67°F). In the presence of any heat at all, the sub-atomic particles in atoms and molecules vibrate. The quantum mechanical mechanism causing this is beyond my scope here, but that vibration causes a release of energy in the form of heat. Heat energy is propagated in one or more of three ways:

- Conduction – If two objects are touching each other, then the heat stored in the hotter will flow to the cooler (that’s the “first law of thermodynamics”).

- Convection – In a gas or liquid, heat energy from a hot container will flow to the fluid by conduction and then the heated fluid will rise, setting up a convection current in the liquid.

- Radiation – Whether or not either of the above occur, there will always be some heat flow in the form of electromagnetic radiation. To me, that is light, whether I can see it or not!

Absolute zero is theoretically unobtainable, because an object at absolute zero would cease all motion, including vibrations within the nucleus and movement of the electrons. All liquids and gasses (including the atmosphere) at this temperature would immediately solidify and collapse to a dense, inert lump, which I don’t believe describes the condition of earth in Genesis 1:2.

This is why I think that it would make no sense for light to have been created subsequent to the creation of matter in Genesis 1:1, whether you interpret that as a summary or a first event.

Since light is so intimately connected with matter, it is unthinkable to me that light would have come first.

Verses 4 and 5 are also difficult for me to accept in a literal sense. “Day and night” are conceptual nouns, and night simply refers to the shadow caused on one side of earth as it rotates away from the sun. But the sun isn’t created until Day 4. Some would say that this verse is where God created time. But time, as now understood by physicists, is part of the fabric of the universe itself (see Implications of God’s Omnipresence and Eternity in Space-Time).

sh’kinah

God’s own sh’kinah is also a light source, and one not connected with matter. It is the light source that led the Israelites out of Egypt, that lit up the top of Mt. Sinai, that resided in the Holy of Holies in the Tabernacle and later the Temple, and that was described in the visions of several of the prophets.

Some commentators have suggested that God’s sh’kinah is the source of the light that God “created” on Day 1. This is absolutely a possibility, but if true, even if it functioned in exactly the same way as the light that we are familiar with, is it meaningful to say that God “created light” on Day 1 if the light he created was fundamentally different from the light that we know? On Day 4, God assigned the responsibility for light-bearing to the sun, moon and stars. In any case, I think the sh’kinah is one of God’s native characteristics, not a later creation.

“Let there be light…”

The Hebrew for this phase is yehi or. With its many linguistic modifiers, Yehi appears 3,561 times in scripture, so it is well understood. To my knowledge, there is complete agreement on the translation here, “let there be“. I am not aware of any context in which it clearly denotes a creative act. It is like saying, “Hey bub, flip on the light, will ya’?”

Interpreting verses 1:3–2:3

As for me, I don’t think that Genesis 1:3–2:3 can be a literal description of how God created the cosmos, because these verses do not describe the immensely complex universe in which we live!

In The Hijacking of Creationism, I mentioned a number of alternative theories proposed by conservatives to explain this passage, as listed in Millard Erickson’s Christian Theology. Another such list is presented below:

The authors of the above table define “concordism” as follows:

In concordist interpretations, God made the earth using the sequence of events described in Genesis 1. In non-concordist interpretations, God created the earth using a different timing and order of events than those described Genesis 1.

According to 19th century theologian, minister and writer, C.I. Schofield, Genesis 1 describes God’s miraculous 6-day rebuilding of an ancient earth after a previous judgement (of earlier humans and/or angelic beings) by inundation. This is a Gap interpretation, from the left side of the table.

What has long intrigued me about Schofield’s Gap Theory is that in the sequence listed, Genesis 1 describes precisely how earth would most likely have recovered from a general flood like that of Noah’s day. If that is true, then both floods were miraculous inundations of the entire planet, and the unnaturally rapid recovery in both cases was also miraculous. This is why I have for years called myself a “gap guy“, or more recently, a “two-flood” guy.

Still, I am no longer adamant about Gap Theory, because it can’t be proven one way or the other, and I don’t share Schofield’s opinion that the judgement leading to the earlier flood was connected to angelic corruption on earth. There is no Biblical evidence of angelic rebellion before Satan appears in the Garden of Eden.

More importantly, after doing extensive study during the last several years in the course of thinking about this series on Creation and another post on Gods and Demons, I feel drawn to a different interpretation that would be much more comprehensible to the people in Moses’ day and well beyond.

A better idea

What was the cultural background?

Regarding the culture of Moses’ day, it is inconceivable that he or his readers would have had the intellectual tools needed to process concepts like mass, energy, the nature of light, or even cosmically vast distances and time scales or a spherical earth.

We tend to think of ancient civilization as a scattering of isolated small city states like Sumer, Akkad, Elam, and even Egypt on the far end of the Fertile Crescent, but they all had a common heritage going back to Babel and even to the Flood.

And even in the distant past there were frequent interactions among peoples. Both war and peace brought people together, either in conquest or in trade. Consequently, there were many similarities between regions, in culture and religion. Though the names and functions of the pagan gods differed somewhat from region to region, there was general agreement about the nature of the world and the duties of the godhead in maintaining its order.

The region that became Israel was part of this milieu. The Israelites were descended from Abraham, who was Mesopotamian. Their later heritage was Canaanite and then Egyptian. The Torah (“Teachings“, the “Five Books of Moses”) that God delivered to His people, had the singular purpose of revealing Himself and His Divine Will to humankind.

In Moses’ day, as in Noah’s and even Jesus’ and beyond, the Israelites shared the beliefs of their Ancient Near Eastern (ANE) neighbors about cosmology (the nature of the heavens and the earth). Though their concept was, of course, deeply flawed, it was functionally adequate for millennia, and it diminished God’s role only in that it ascribed His creation to false creators. The following diagram shows the essence of what was universally accepted as true cosmology in the ANE.

Note that this is also clearly the cosmology described in Genesis 1!

The earth was a roughly disk-shaped island floating on the sea (possibly supported on “the pillars of earth”) and covered with a dome, the “firmament” of KJV. The sea was not only below the earth and feeding its springs (the “fountains of the deep”), but also covered the dome above (the “waters above the firmament”). In some versions the dome was supported at its rim by a ring of mountains (the “pillars of heaven”). The sun and moon traveled across the sky below the dome, sinking into the sea or through doors in the west, and traveling back east through the underworld to rise again. The stars and planets followed fixed grooves beneath the dome. Rain occurred when windows in the dome (the “windows of heaven”) were opened by the gods.

No matter how one interprets Genesis 1, the central issue that had to be addressed by God was that each element in the above diagram was believed to either be a god or goddess, or to be governed by one. And, of course, it was believed that all owed its existence to one or more chief creator gods. Rather than “nothingness” before creation, the cosmos existed, but was in a state of chaos (formlessness, or tohu wabohu, as defined above); thus, creation amounted to bringing order out of disorder.

So, what are my views?

A Genesis 1 alternative that makes total sense to me now is related to historical observations that the Israelites shared the culture and cosmology of the surrounding peoples. The Genesis account and the Bible as a whole condemns the pagan polytheistic connection, but does nothing to dispel the cosmological misconceptions, which were still believed by most cultures, including Israel’s, well into the Christian era.

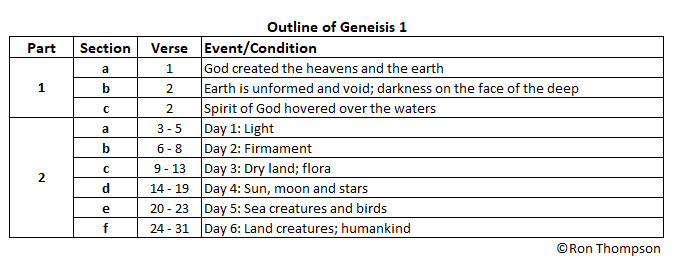

The chart below displays relationships recognized by many conservative theologians who hold to a literal, Concordist, interpretation of Genesis 1; however, rather than interpreting the chart as an account of literally how God created the physical cosmos, I think it is better understood as a very abbreviated poetic description of the finished product.

by Deborah B. Haarsma and Loren D. Haarsma

Understood in that way, it becomes one version of a Creation Poem Interpretation of Genesis 1. As such, it is essentially a polemic (a statement argumentatively refuting an opinion or doctrine held by others) against the creation myths of pagan cultures who credit their false gods, who most certainly did not create or rule the cosmos!

The ANE held no conception of infinite time or eternity. They thought no farther back than the initial chaos (compare Genesis 1:2), out of which arose the creator god, who then began to assemble the cosmos from the chaos. Only Yahweh claimed to be eternal and uncreated, and to create ex nihilo.

Whereas modern man sees existence as material in nature, with tangible substance and physical properties, it wasn’t enough for the ancients that something was visible and occupied space—as stated by John H. Walton in Ancient Near Eastern Thought and the Old Testament, it had to first “come into existence” metaphysically by being “separated out as a distinct entity, given a function, and given a name.”

A key insight that I have gleaned from Walton and others who have professionally studied the ANE is that the ancients viewed the ontological nature of the cosmos, i.e., “the nature of that which exists” in terms of function, whereas moderns view it in terms of substance. In other words, when a Big Bang Creationist like me thinks of God’s handiwork, I see mass and energy, bosons and fermions, stars and planets, rocks and trees, etc. A Young Earth Creationist similarly sees a universe of substance. To the ancients, in contrast, the substance of things is only incidental to their functions.

Consequently, I’m beginning to understand that God’s purpose in Genesis 1 was to ignore the misconceptions of the ANE regarding the physical nature of the cosmos, since that was a triviality to pretty much 100% of the population, and to say, in ways they would understand, “I, Yahweh, brought it into being [verse 1] and gave it function [the rest of Genesis 1].”

In this way of thinking,

- Days 1 and 4 were about time, seasons, and the cosmic objects that differentiate them;

- Days 2 and 5 were about the waters below and above, and about their denizens; and

- Days 3 and 6 were about the land and its fecundity.

What point was God then making?

According to Walton, “The records of events in the ancient world were not given so that the reader could reconstruct the event. They were given so that the reader could understand the significance of the past for the present. In that sense, outcomes were more important than the events themselves.”

The pagan creation myth most familiar to modern scholars today is the Enuma Elish, from the Assyrian Library of Ashurbanipal at Nineveh. I’ll close this post with a comparison of Genesis 1 with this pagan document, which I think clearly illustrates God’s point:

by Deborah B. Haarsma and Loren D. Haarsma

Bibliography

Haarsma, Deborah B., Loren D. Haarsma, Origens: Christian Perspectives on Creation, Evolution, and Intelligent Design,2011, Grand Rapids: Faith Alive Christian Resources.

Walton, John H., Ancient Near Eastern Thought and the Old Testament, 2nd ed., 2018, Grand Rapids: Baker Academic.

Zuck, Roy B., Basic Bible Interpretation, 1991, Colorado Springs: Cook Communications Ministries

Next in series: Quantum Freewill