Posted on:

Modified on:

This post has a dual purpose:

- To discuss the Jewish concepts of yetzer (human inclinations) and their antagonist, Yotzer (Godly influence), which Paul alluded to over and over again in his epistles.

- To examine the use of those concepts in Paul’s defense of “the Law” in Romans 7. I chose this example as a follow-up to my last post, Fulfilling the Law: Matthew 5:17–19.

In his important book, Israelology, the Missing Link in Systematic Theology, Messianic scholar Dr. Arnold G. Fruchtenbaum takes the position that, “The Law of Moses has indeed been rendered inoperative.” In Appendix II, on page 908 of the 2001 edition, he cites a number of passages to prove his point—to which I disagree!

I want to be clear that on most issues I like Dr. Fruchtenbaum very much. In particular, his Israelology is easily the best source I have found describing the ubiquitous Dispensational and Covenant theologies. I also thoroughly enjoyed his book, The Footsteps of the Messiah: A Study of the Sequence of Prophetic Events.

Jewish sin nature concepts

Contrary to the myths of liberal Christianity, Paul did not invent the New Testament Church. But neither did he learn it from Jesus’ disciples, who he initially avoided. Instead, I believe his training came directly at the hands of God (ala Moses) and/or angels (ala Daniel), during his post-Damascus sojourn in Arabia (discussed here).

But his ministry was also heavily informed by his extensive knowledge of Jewish theology, gained as a Pharisee and a student of the great rabbi, Gamaliel the Elder, who was himself a Nasi (President) of the Great Sanhedrin and the grandson of Hillel the Elder, one of the era’s three greatest Jewish sages. These facts are pertinent to this topic.

Yetzer and the “Old Man”

The concept of human “inclination of mind” is well established in ancient Judaism. The Hebrew term is יֵצֶר, transliterated as yetzer, yetser, yatsar, or something similar. Since Hebrew uses an alphabet (actually, an aleph-bet) without vowels, the spellings of transliterated words are mostly unimportant.

Pronunciation is determined by local custom, especially with respect to whether one’s Diaspora heritage is Ashkenazi (European) or Sephardi (Middle Eastern). I’ll go with Strong’s phonetic spelling of yay’-tser, here.

In Jewish thinking, every child, male or female, is conceived with an inclination to do evil, yetzer hara (“the evil inclination”), and an inclination to do good, yetzer hatov (“the good inclination”). The evil inclination is “born” with the child, but the good inclination is not born until adolescence. Both persist for the remainder of life. Note that both of these inclinations are innate characteristics, and common to all humans.

Prior to the birth of yetzer hatov, it is the parents’ responsibility to teach the child right and wrong and to maintain discipline. As the child enters adolescence, around the age of 13 (boys) or 12 (girls), yetzer hatov is born and begins to grow and combat yetzer hara. The adolescent thus gains an internal maturity and sense of responsibility that begins to replace childish self-absorption and expedience.

Note that yetzer hatov has no influence on the child prior to its birth at the child’s puberty. At its birth in the young adolescent, being itself some 13 years “younger” than yetzer hara, it is always at a disadvantage, which explains why even mature adults continue to struggle with sin.

Paul, in his writings, apparently considers this unbalanced set of hypothetical inclinations to be what he calls the “old man” or the “old nature.” We would call it “the conscience.”

Yotzer and the “new Man”

Another Jewish concept that is applicable here is that of God as the Yotzer Ohr (“Creator of light”). This title, of course, reflects His first creative act in Genesis 1. Each day, during the morning (shacharit) prayers, before reciting the Shema, two blessings are said. One of those is the Birkat Yotzer Ohr, “Blessed are you, LORD our God, King of the universe, who forms light and creates darkness, who makes peace and creates all things… Blessed are you, LORD, who forms light.”

Paul, as we all know, presents the New Covenant believer, indwelled by the Holy Spirit, as having a new, Godly inclination, which he calls the “new man” or the “new nature.” He is clearly equating this godly inclination with the Yotzer Ohr concept.

Yetzer vs. Yotzer

Thus, the continual struggle between the old nature and the new nature. In good Hebrew fashion, many Messianic Jewish believers have latched onto the poetic similarity in the two words, yetzer and Yotzer, to describe that tension as yetzer verses Yotzer. I like that!

In the remainder of this post, I will be illustrating Paul’s application of yetzer vs Yotzer in his discourse on the Law and the continuity of the Mosaic Covenant in Romans 7:1–6.

Background

The Epistle addressees

Who was Romans written to? Unlike most of the epistles, Romans was not written to “the church [at Rome].” Romans 1:7a tells us that he addressed it to “all those in Rome who are loved by God and called to be saints.” Rome was a big city and probably had several local churches. We know from later chapters that some of the Roman believers were Jewish, but since the city was overwhelmingly Gentile, it’s likely that most of the believers there were Gentile.

That likelihood is reinforced by a look at the date of writing. Estimates mostly place it in the range of AD 56–58. Although the earliest Christians in Rome were probably Jewish, Emperor Claudius expelled all Jews from the City in AD 49. When the expulsion was ended after Claudius’ death in AD 54, those Jews who returned found that Gentile Christians had taken over their synagogues.

When Paul wrote his epistle, I think that the Jewish minority in the churches of Rome was small, and resentment was high.

That gentiles were intended to be Paul’s primary recipients is plainly stated in the letter’s opening:

Romans 1:13 (CJB)

[13] Brothers, I want you to know that although I have been prevented from visiting you until now, I have often planned to do so, in order that I might have some fruit among you, just as I have among the other [λοιπός, loipos, other, remaining, rest of the] Gentiles.

Nevertheless, some passages in the epistle were clearly intended for Jewish believers, as he implied in verse 7:1a (CJB): “Surely you know, brothers—for I am speaking to those who understand the Torah…”

The roots of gentile unrighteousness

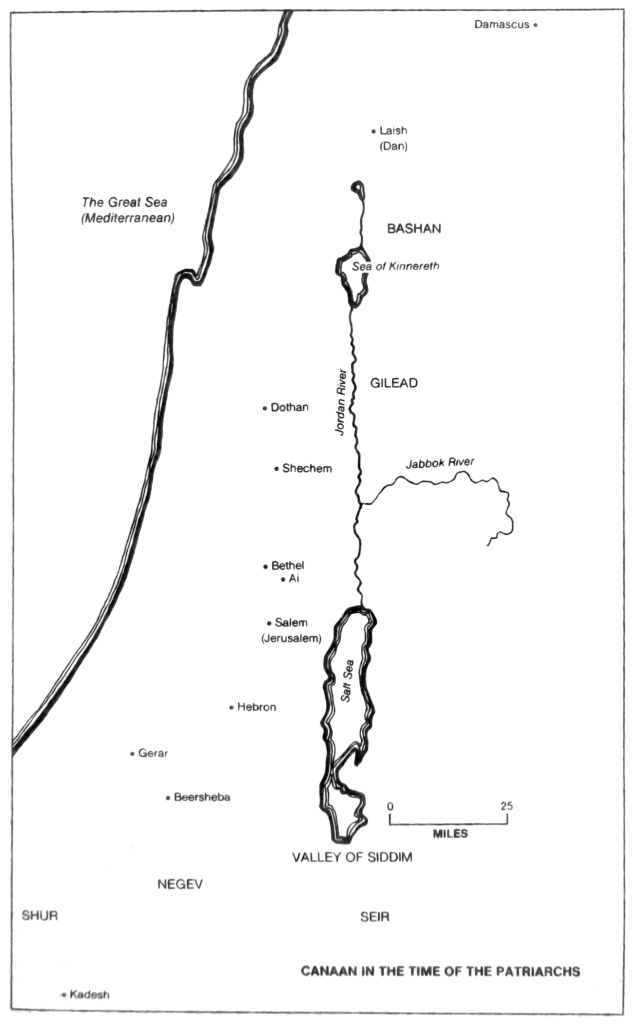

In Romans 1:18–32, Paul sets the stage by explaining the reasons for, and the results of, Gentile unrighteousness. In the ancient, postdiluvian world, all humans were descended from four men and four women. All eight had seen the flood, which I believe was global, and all of them had seen the evil that led to the flood. The Tower of Babel was built just four generations later, and in those days before writing was invented, when troubadours abounded and stories were spread verbally, you can bet that tales of creation, flood and tower were still fresh.

The fact that every culture ended up with creation stories and flood stories proves that knowledge persisted, and Romans 1:20 bears that out:

Romans 1:20 (ESV)

[20] For his invisible attributes, namely, his eternal power and divine nature, have been clearly perceived, ever since the creation of the world, in the things that have been made. So they are without excuse.

From verse 24, the rest of Romans 1 reveals the final result of the Tower of Babel incident, which I will discuss more fully in a future post. Briefly, God gave them up to “the lusts of their hearts”, verse 24. That is yet another name for yetser hara, the evil inclination.

Out of this milieu, God chose one man, Abram of Ur, to father a people that He would call His own, Israel.

The Value of the Law to gentiles

Romans 2 continues the theme of unrighteousness, particularly as it relates to Gentiles, and begins a discussion on the value (or not) of Gentiles adopting Torah.

Romans 2:12,14–15 (ESV) alterations mine

[12] For all who have sinned without the law will also perish without the law, and all who have sinned under the law will be judged by the law.

…

[14] For when Gentiles … who do not have the law, by nature do what the law requires, they are a law to themselves, even though they do not have the law. [15] They show that the work of the law is written on their hearts, while their conscience also bears witness, and their conflicting thoughts accuse or even excuse them[.]

In the above quotation, I removed a comma after the word “Gentiles” in verse 14. Biblical Greek was written without punctuation, so the comma is interpretive and not part of the inspired text. Inclusion of the comma implies that what follows is comparing gentiles with Jews, but verse 12 sets the correct context, gentiles who have not chosen circumcision. This chapter is contrasting Gentiles who adopt Torah (the Law) with those who don’t. I think the comma is in error.

Gentiles without the Law (i.e., those who have not officially become Jewish proselytes) who are living righteously, as if they are Jews, demonstrate that indeed, the New Covenant is written on the heart. Also, like righteous Jews, their balance of yetser hara and yetser hatov either condemns or excuses them. But unrighteousness dulls the conscience.

Verse 25 is an important statement regarding the value of Gentile conversion to Judaism:

Romans 2:25 (ESV)

[25] For circumcision indeed is of value if you obey the law, but if you break the law, your circumcision becomes uncircumcision.

Quite simply, if Gentile proselytes to Judaism obey the precepts of Torah, then yes, it is a tremendous spiritual and social value to them, as it is to obedient ethnic Jews; otherwise, they have only joined a club with stringent requirements and no lasting benefits. Not to mention significant physical pain for males.

Although this chapter (Romans 2) applies only to Gentiles, it is worth noting that Paul in other places makes a similar point to Jews: if you don’t obey the dictates of your own Jewish laws, then you might as well not be Jews.

Exposition of Romans 7:1–6

Since this is the heart of my argument in this post, I have been researching it carefully. As I’ve mentioned elsewhere, I have an extensive library of Bible texts, commentaries, language resources and other materials. For Romans, in particular, I have a favorite commentary: A commentary on the Jewish Roots of Romans, by Joseph Baruch Shulam, Director of Netivyah Bible Instruction Ministry in Jerusalem.

Here is the text we will be analyzing, with a goal of understanding, in particular, the meaning of verse 6:

Romans 7:1–6 (ESV) emphasis mine

[7:1] Or do you not know, brothers —for I am speaking to those who know the law—that the law is binding on a person only as long as he lives? [2] For a married woman is bound by law to her husband while he lives, but if her husband dies she is released from the law of marriage. [3] Accordingly, she will be called an adulteress if she lives with another man while her husband is alive. But if her husband dies, she is free from that law, and if she marries another man she is not an adulteress.

[4] Likewise, my brothers, you also have died to the law through the body of Christ, so that you may belong to another, to him who has been raised from the dead, in order that we may bear fruit for God. [5] For while we were living in the flesh, our sinful passions, aroused by the law, were at work in our members to bear fruit for death. [6] But now we are released from the law, having died to that which held us captive, so that we serve in the new way of the Spirit and not in the old way of the written code.

Verse 1:

First, note that that this section is addressed specifically to Jews in the Roman churches: brothers … those who know the law. What Paul is doing here is reminding them of something that they are already well aware of, that the law is binding on a person only as long as he lives.

That’s pretty logical—you can’t sacrifice, recite the Shema, attend prayers, teach your children to be Torah observant, or do anything else, once you have died!

Why do I spend time here on something so obvious? Because it was a matter of formal consideration by the scholars of the day, who wanted to understand the reason for everything that God had to say. In considering

Psalms 115:17 (ESV)

[17] The dead do not praise the LORD,

nor do any who go down into silence.

The Babylonian Talmud records the words of Rabbi Yohanan, an ancient sage:

Talmud Shabbat 30a

That which David said: “The dead praise not the Lord,” this is what he is saying: A person should always engage in Torah and mitzvot before he dies, as once he is dead he is idle from Torah and mitzvot and there is no praise for the Holy One, Blessed be He, from him. And that is what Rabbi Yohanan said: What is the meaning of that which is written: “Set free among the dead, like the slain that lie in the grave, whom You remember no more” (Psalms 88:6)? When a person dies he then becomes free of Torah and mitzvot.

Verse 2:

Paul then draws an analogy from common Jewish case law to support the point he is about to make, that the Law ceases to rule not only the obligations of the dead, but also obligations towards the dead. Verse 1 made the obvious point that once a person is dead, he or she is no longer obligated to observe, i.e., to keep or obey, the tenets of Torah. Certainly, a dead husband is no longer required to meet the terms of the ketubah, or marriage contract. Likewise, the living wife of the dead husband is released from her obligations under the ketubah.

This is not a trivial point. She could of course remain celibate for the rest of her life, and some might say that she should. Why? Because Torah is silent on the issue. It mentions only divorce as freeing the wife.

What the Old Testament says on the subject of divorce (aside from prophetic texts concerning Israel as God’s wife) is found only in Deuteronomy 24:1–4. What is pertinent for this discussion is:

Deuteronomy 24:1 (CJB)

[24:1] “Suppose a man marries a woman and consummates the marriage but later finds her displeasing, because he has found her offensive in some respect. He writes her a divorce document [called a “Get“], gives it to her and sends her away from his house.

On what authority, then, can a woman be freed by the death of her husband? Talmud Kiddushin 13a records:

A woman is acquired by, i.e., becomes betrothed to, a man to be his wife in three ways, and she acquires herself, i.e., she terminates her marriage, in two ways. The Mishna elaborates: She is acquired through money, through a document, and through sexual intercourse.

A woman acquires herself through a bill of divorce or through the death of the husband. The Gemara [a collection of rabbinical analyses and commentaries on the Mishnah] asks: Granted, this is the halakha with regard to a bill of divorce, as it is written explicitly in the Torah: “And he writes for her a scroll of severance, and gives it in her hand, and sends her out of his house; and she departs out of his house and she goes and becomes another man’s wife” (Deuteronomy 24:1–2). This indicates that a bill of divorce enables a woman to marry whomever she wishes after the divorce.

But from where do we derive that the death of the husband also enables a woman to remarry? The Gemara answers: This is based on logical reasoning: He, the husband, rendered her forbidden to every man, and he has permitted her [implicitly, by his death]. Since the husband is no longer alive, there is no one who renders her forbidden.

Verse 3:

In verse 3a, “Accordingly, she will be called an adulteress if she lives with another man while her husband is alive”, Paul sums up the Torah’s indictment of an adulterous woman, from:

Leviticus 18:20 (CJB)

[20] You are not to go to bed with your neighbor’s wife and thus become unclean with her.

Leviticus 20:10 (CJB)

[10] “‘If a man commits adultery with another man’s wife, that is, with the wife of a fellow countryman, both the adulterer and the adulteress must be put to death.

Deuteronomy 22:22 (CJB)

[22] “If a man is found sleeping with a woman who has a husband, both of them must die—the man who went to bed with the woman and the woman too. In this way you will expel such wickedness from Isra’el.

In 3b, “But if her husband dies, she is free from that law, and if she marries another man she is not an adulteress”, Paul is reminding the Roman Jews again of the case law (Oral Torah) extension of “release by divorce” to “release by death”, and applying that extension to contemporary interpretations of Deuteronomy 24:2, “She leaves his house [after receiving the divorce decree and being sent away], goes and becomes another man’s wife”, which held that this implies the right of a divorced wife to remarry without prejudice.

Verse 4:

We now come to a key crossroads for our understanding. Verse 7:4 begins with the Greek “consecutive particle”, ὥστε (hōste), which has a wide range of translations in the Bible. In this verse, many versions render it as “therefore”, which is one of those ubiquitous words that make Bible teachers say you should ask yourselves, “what is it there for?”.

The ESV has it as “likewise”, which I think makes better sense in the context. In this case, though, you still have to ask, “like what?” Most commentators, including Shulam, tie it to 7:1–3, but that raises a conundrum: in that passage, Paul has reminded his Jewish readers that, with respect to marriage commitments, the Law is “dead” to the Jewish widow. But in verse 4, it’s the other way around: “you also have died to the law through the body of [Messiah]”. Shulam says, “[Paul] then conflates the position of the married woman and her husband.”

That may be a fair statement, but whether “we Jews” are dead to the Law, or the Law is dead to “us”, we still don’t know what that means. In the case of the widow, clearly it is only that one provision of Torah that is “dead”, and it is “dead” only to her and other Jewish widows. Is verse 4 making a blanket statement that the Law is completely abrogated for Jews, or that Jews are no longer bound by the Law in any fashion?

If that’s what Paul is saying, then he is contradicting Jesus’ clear statement in Matthew 5:17–19. That, He would not and could not do! To borrow one of Paul’s favorite phrases, “μή γένοιτο (mé genoito, may it never be!)”

I am proposing that “likewise” in verse 4 refers, not to the parenthetic analogy in verses 1–3, but rather to the parallel discussion in the previous chapter, addressed to gentile believers.

Not only does that make more sense from a contextual standpoint, but it can be demonstrated from a translational standpoint, as well. I pointed out above that Biblical Greek had no punctuation, and I then removed a comma in the English to clarify the translation of Romans 2:14. In the same way, Paul’s epistles were not divided into chapters and verses, so those, too, are uninspired.

I believe that verses 7:1–3 are a deliberate segue between the chapter 6 discussion of gentiles and the Law, and the chapter 7 parallel discussion of Jews and the Law.

Précis of Chapter 6:

Exegesis of chapter 6 is not my task here, but we clearly need at least a summary…

In Romans 6, Paul presented to gentile believers the concept of salvation as a state of being “dead to sin.”

He introduced this idea in verse 2 by asking the question, “How can we who died to sin still live in it?”

The answer began in verse 3 with another question, “Don’t you know that all of us who have been baptized into [Messiah] Jesus were baptized into his death?” He then amplified in the following two verses:

Romans 6:4 (ESV)

[4] We were buried therefore with him by baptism into death, in order that, just as [Messiah] was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, we too might walk in newness of life.

[5] For if we have been united with him in a death like his, we shall certainly be united with him in a resurrection like his.

Literally dead? Of course not. In the next verse, he makes that explicit by introducing them to the Jewish concept of yetzer hara, the evil inclination:

Romans 6:6 (ESV) emphasis mine

[6] We know that our old self [yetzer hara] was crucified with him in order that the body of sin might be brought to nothing, so that we would no longer be enslaved to sin.

It’s not that their hearts, lungs and nervous systems had ceased functioning, but rather that their evil inclinations had been freed from slavery to sin, just as the Jewish widow in the illustration of 7:1–3 was free from bondage to her deceased husband under Jewish case law.

In the remainder of chapter 6, Paul explained the spiritual consequences of this death to sin, and their obligation to rein in their mortal bodies and not obey the carnal passions.

In verse 14, Paul closes his discussion with the Roman gentile believers by telling them that, “…sin will have no dominion over you, since you are not under law but under grace.” I’ll have more to say about that at the end of this post!

Verse 4 continued:

If one understands that Romans 6 is about the disempowerment of the gentile evil inclination and new life in Jesus, and Romans 7 is about the disempowerment of the Jewish evil inclination and new life in Jesus, then the “likewise” of 7:4 is explained. The parallelism in the two passages can be plainly seen in the following, for example:

Romans 6:4–5, 7:4 (ESV)

[6:4] We were buried therefore with him by baptism into death, in order that, just as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, we too might walk in newness of life. [5] For if we have been united with him in a death like his, we shall certainly be united with him in a resurrection like his.

…

[7:4] Likewise, my brothers, you also have died to the law through the body of Christ, so that you may belong to another, to him who has been raised from the dead, in order that we may bear fruit for God.

On “we may bear fruit for God”, Shulam writes, “Having put his evil inclination to death and died to sin, the believer is enabled to perform God’s will in keeping his commandments, and so to serve God in the ‘newness of (eternal) life.'”

Verse 5:

In contrast to the Godly life lived in conformance to Yotzer, or Godly inclinations, the fleshly life lived in conformance to yetzer hara, or evil inclinations, results in “our members” bearing “fruit for death.”

The effect of Torah, the Law, on unbelieving Jews who have not been freed from bondage to yetzer hara is to arouse the sinful passions by its provocative prohibitions.

Verse 6:

The statement, “…now we are released from the Law” is problematic because most Christians who read it conclude that it is clearly pronouncing an end to, at least, the Mosaic Covenant.

That’s not the way I read it!

That interpretation ignores the conjunctive phrase, “But now”, at the beginning of the verse. The Greek νυνί δέ (nyni de) translates more directly as “Now, however.”

Given the conjunction, I would paraphrase verses 5 and 6, combined, to “While we were living in the flesh and controlled by yetzer hara, our sinful passions were aroused by the Law; but now however, with yetzer hara subdued by Yotzer Ohr, the Law no longer has that power over us.”

Law and Grace summarized

In times past, yetzer hara (the evil inclination) dominated yetzer hatov (the good inclination). The contest was so unequal that God first brought the Flood, then after Babel, He “deglobalized” the earth and “gave them [the new nations] up in the lusts of their hearts to impurity, to the dishonoring of their bodies among themselves…”, Romans 1:24. Then, He called Abram out of Ur…

The Mosaic Covenant reveals God’s will for Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, and all of Jacob’s descendants, to mark them as a special people set apart (that is, “holy”) for Him in the face of gentile hostility. Torah is a huge blessing for Jews because of the rewards it offers, but “to whom much was given, of him much will be required”, Luke 12:48. God’s requirements for Old Testament gentiles were far less stringent, and based mostly on “natural law“, i.e., the conscience. Because human conscience (good inclinations, yetzer hatov) is much weaker than human rebellion (evil inclinations, yetzer hara), sin proliferated among the gentiles.

The Covenant codified a set of 613 inspired commandments for Jewish observance (never for the gentiles!), and Oral Torah (later recorded in the Mishna, then the Talmuds), though not inspired and thus not always strictly in accordance with God’s will, provided for administration, interpretation and case law. The Prophetic books and Wisdom literature (inspired but sometimes theologically obscure) provided more content to educate and motivate Israel and to warn her enemies.

I believe that the inspired New Covenant works in concert with the Mosaic Covenant, rather than replacing it. The Church, “the Jew first and also … the Greek [gentile]”, Romans 1:16, is blessed by the indwelling Holy Spirit, and thus the Yotzer Ohr (I call it the Godly inclination), which supplements the innate yetzer hatov (the good inclination, or conscience).

Together (but primarily by the power of the Yotzer Ohr), these two now dominate yetzer hara. That is not to say the yetzer hara is now absent, but its power to dominate has been put to death.

As a result of the indwelling Spirit, gentiles now partake in the blessings of the Jews, though not in God’s promises to them. As coparticipants with Israel in the New Covenant, what are the provisions of the Law “written in our hearts?”

I believe that the New Covenant Halakhah (“way of walking”, see “An Expanded View of Torah/Nomos“) consists in a Spirit-guided obedience to Godly principles, not in the legalistic observance of mitzvoth (Torah commandments).

This was clearly stated early in the epistle:

Romans 3:9a (ESV)

[9b] … we have already charged that all, both Jews and Greeks [gentiles], are under [controlled by] sin…

Romans 3:20 (ESV)

[20] For by works of the law no human being will be justified in his sight, since through the law comes knowledge of sin.

Romans 3:28–31(ESV)

[28] For we hold that one is justified by faith apart from works of the law. [29] Or is God the God of Jews only? Is he not the God of Gentiles also? Yes, of Gentiles also, [30] since God is one—who will justify the circumcised by faith and the uncircumcised through faith. [31] Do we then overthrow the law by this faith? By no means! On the contrary, we uphold the law.

According to verse 31, even though salvation is by faith, not works, Paul is making it clear that the Law is still alive and fully valid!

I’m now going to quote that last passage and a few others in a Jewish translation that paraphrases a few things with a bit more clarity:

Romans 3:28–31 (CJB)

[28] Therefore, we hold the view that a person comes to be considered righteous by God on the ground of [faith], which has nothing to do with legalistic observance of Torah commands.

[29] Or is God the God of the Jews only? Isn’t he also the God of the Gentiles? Yes, he is indeed the God of the Gentiles; [30] because, as you will admit, God is one. Therefore, he will consider righteous the circumcised on the ground of [faith] and the uncircumcised through that same [faith]. [31] Does it follow that we abolish Torah by this [faith]? Heaven forbid! On the contrary, we confirm Torah.

The following passages make it clear that “salvation by grace through faith” is not a New Testament invention—that has always been the way of salvation!

Romans 4:3 (CJB)

[3] For what does the Tanakh [Old Testament] say? “Avraham put his trust in God, and it was credited to his account as righteousness.” (Genesis 15:6) [4] Now the account of someone who is working is credited not on the ground of grace but on the ground of what is owed him. [5] However, in the case of one who is not working but rather is trusting in him who makes ungodly people righteous, his [faith] is credited to him as righteousness.

Romans 4:11–12 (CJB)

[11] In fact, he [Abraham] received circumcision as a sign, as a seal of the righteousness he had been credited with on the ground of the [faith] he had while he was still uncircumcised. This happened so that he could be the father of every uncircumcised person who trusts and thus has righteousness credited to him, [12] and at the same time be the father of every circumcised person who not only has had a b’rit-milah [the rite of circumcision], but also follows in the footsteps of the [faith] which Avraham avinu [Abraham our father] had when he was still uncircumcised.

Torah observance in the Church

The first church council, at Jerusalem, recorded in Acts 15, settled the issue of whether or not gentiles in the church need to become Jewish proselytes and obey the dictates of Torah’s commandments. The answer is “No”, except for a few key issues necessary for fellowship with their Jewish brethren.

Neither the council, nor anything else in scripture, absolved Jews from Torah faithfulness! Does that mean that Jewish Christians in non-Jewish churches or Messianic synagogues are required to be “observant”? Perhaps not, but I think that at the very least, a nonobservant Jew forfeits Jewish promises in the present and coming age.